Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the fifth issue of our Journal, which has a botanical slant. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures.

Photography Michaela Skovranova, @mishkusk; Words Dan Down

A couple of years ago at a community meet-up in Narrabeen on Sydney’s Northern Beaches, Clarence, a Yaegl man from the Far North Coast, met Adam, a descendant of the Garigal and Gadigal people.They came up with an idea.

The greatest ideas are often the most simple, and this one emerged from a discussion about native plants and the wealth of Indigenous know-how surrounding them. They recognised that people are hungry for Indigenous knowledge, for healthy food, and they knew that native plants could deliver these things while also fostering biodiversity and tackling climate change. What’s more, they realised that sharing their understanding of native plants would not only achieve all this, but could also reconnect every Australian with nature.

To achieve these grand goals they formed Bush to Bowl, with the aim of ‘cultivating Aboriginal culture and bringing community together through bushfoods’. From a parcel of land they are using at a Sydney school, they have started sharing their passion for native plants and the benefits they bring to personal health and wellbeing, as well as the wider suburban landscape.

Adam Byrne, a landscaper and horticulturist, and Clarence Bruinsma, an Aboriginal education consultant, and personal development, health and physical education teacher, bring the required skills to realise their dream. “We have a very big vision. We are creating an educational space where the community can come and take part in workshops, learning about these foods, how to use them, and set up permaculture sustainable practices in their own backyards,” says Adam. “But we also want to make a space where Aboriginal people can come and feel safe, engage and share Culture.”

Clarence says all this while sipping from a mug of Lemon myrtle tea. “It's pretty much a daily ritual for me, the antioxidant levels in Lemon myrtle tea are 10 times that of a green tea. And we know that antioxidants fight different carcinogens.”

And the act of gardening, of getting your hands into the soil to plant and tend to native species brings mental health benefits too. “We know that by connecting to and being in nature there is an element of relaxation that happens to the brain and stress levels dramatically decrease, reducing feelings of depression and anxiety,” says Adam. “Through conversations around our foods, people are really fascinated by Aboriginal culture and the knowledge that's there.”

It’s knowledge that we could desperately use right now in the fight to tackle climate change. “When we look at our food industries, one-third of all food that we produce and then buy goes to landfill,” says Clarence. “And that's resulting in greenhouse gases and pollution. There's the pollution of transporting that food; there's the pollution of the packaging; there's also the pollution from producing all that food. When we can sustainably grow our own foods in our own backyards, we eliminate that and take care of Country.”

Thankfully caring for Country, as Adam and Clarence teach it, is as easy as letting nature do the hard work, just letting it get on with it. It's about mirroring nature. "That's what the old people did, what our ancestors did, it's just mirroring what the planet already does.

“When I look at a garden all I see is a little ecosystem, and if it’s a completely blank space, I ask ‘How would I mirror Country, how would I mirror the bush right here?’ Obviously, I can't reflect something so beautiful, but you just try and create another ecosystem and then just leave it.”

People can come to a Bush to Bowl workshop and learn about which native plants to grow in their backyard, from plant propagation through to harvesting, and then which plants can become a staple food. You can then procure plants you’ve learnt about through the nursery, like saltbush, “which can be used like a seasoning,” says Adam. “Or there’s a Tetragonia, like a native spinach, which is a warrigal green.”

Caring for Country means caring for local biodiversity too, and part of Bush to Bowl’s philosophy is making sure that local insects and birds benefit from your garden as much as you do. “There’s a Bush basil that has a really beautiful, stunning purple flower that bees just seem to love,” says Clarence.

“It's one of the most important things,” says Adam. “Having a chat with one of our uncles, he wants you to think about providing for the insects and the animals around as much as you want to provide food for yourself. We can always put food in our bellies, but how are we supporting animals as well. By putting native plants in your garden it helps support that biodiversity.”

"You take care of Country and it takes care of you. A lot of our First Nation culture really has us connected to everything around us."

Clarence Bruinsma, Bush to Bowl.

“And that's a beautiful thing. When you put your hands in the soil and you put a plant in, or you actually go and take your own food from your own garden, knowing it's native to the area, there's a real sense of connection. There’s a real sense of self fulfilment because you're supporting yourself, but you're also supporting Mother Earth and all those other animals that are around you.

“If you try to see a bigger picture and think about Country as much as you think about yourself; if everyone saw the planet like that, as one thing that we're connected with, then it would be a different world.”

Learn which native plants you should be planting in your backyard and how to care for Country, at a Bush to Bowl workshop.

Words and photography by Michaela Skovranova @mishkusk / mishku.com

What does your work with orchids entail?

I am a research scientist at the Australian Tropical Herbarium, where I lead the Orchid Research program. Our research is mainly using novel genomic approaches to understand the evolution, systematics and diversity of Australian orchids.

Can you tell us about any specific work you're doing?

Our research has two main objectives. One side of it is to understand Australia's orchid diversity from an evolutionary perspective. The other is the conservation perspective, looking at the diversity in closely related orchids to find out whether they represent one or many species. To help conserve orchids, conservationists need to know what they need to protect; whether it is a rare species or whether it is a more widespread species. Understanding where the species boundaries are in orchids is still a very big challenge.

We are currently working on several conservation genomics projects on threatened Australian orchid species, one of which is concerned with flying duck orchids. There have been a fewer number of flying duck orchids recognised in the past, and then new species described over the past 15 years. But to determine their conservation status, it has to be established whether they are valid species and to know more about the genetic diversity within those species to help conservation plans.

How many different orchid species are there thought to be in Australia?

That is a really difficult question to answer. Conservative estimates are that there are about 1,300 species; less conservative estimates are around 1,800 species. And this discrepancy is really based on that question of species delimitation. In other plants that have more conserved traits than orchids, there are clearer traits to distinguish species, whereas in orchids it is not that easy to determine. For many of those orchids we already have scientific names available, but we do the genetic work to understand species boundaries in much more detail.

People love orchids for their array of shapes, sizes and colours. What makes them unique to other flowering plants?

One thing that is unique to orchids is that they have evolved a way in their flower development to allow them to be much freer in the way they can create different shapes and colours. Most plants have very symmetrical flowers, where all parts of the sepals or petals have a similar colour or shapes; in orchids there's a great diversity in colour and shapes of those flower segments, even within a single flower. So that is one major difference. And that is also why we find orchids so attractive, because they have this sheer diversity.

Orchids have also evolved highly specific interactions with other organisms, especially pollinators and fungi, and have evolved specific adaptations to make those relationships very strong and helpful for the plant. For example, all orchids depend on a fungus to germinate, which allows the plants to have tiny dust-like seeds that can disperse very well.

And many orchids have evolved very strong relationships with pollinators, often on a species to species basis that ensures that the orchid is effectively pollinated and does not receive pollen from other species the pollinator may have visited. So, these two aspects of orchids make them very special.

There are some very unusual species, including the recent discovery of an underground orchid. What evolutionary advantage has been discovered for such an unusual flower?

The underground orchid is an extreme example of that relationship with the fungus. In all orchids, the fungus is critical for germination and that relationship often continues with mutual benefit where the fungus and the plants exchange nutrients with each other.

But the underground orchid became completely dependent on the fungus for nutrients and no longer needs to carry out photosynthesis. It can therefore afford to stay underground for nearly its entire lifecycle. But as the flowers still require pollinators, the flowers still have to come up.

And the flowers just barely come up, they stay close to the ground under the leaf litter and then get pollinated and the seeds are dispersed above ground. And then the plant can retreat below ground again.

Are there any other strange orchids in Australia that we should hear about?

Another extreme form of an orchid that we find in Australia are the ribbon roots. They are epiphytes often found on little twigs, and they can cope with drier conditions in seasonal climates than epiphytes from moister regions. Epiphytes usually require consistent moisture throughout the year.

The way the ribbon roots solved the problem of enduring the drier times of the year is that they don't have leaves anymore, which reduces their water loss through the leaf surface. Instead, ribbon roots absorb sunlight and do photosynthesis within their roots, which are green. This is quite remarkable.

Do you have a favourite orchid species?

That is the hardest question. There are so many exciting, stunning orchids out there. But I made a choice, and that is the Queen of Sheba orchid. It has a really unusual flower that doesn't look like an orchid flower, but rather like a lily flower. And that is because it mimics lilies that have a nectar reward for insects to come to the flower and pollinate it. However, the Queen of Sheba doesn't offer any nectar, so it is a deceptive orchid.

The flower colours are also really outstanding. So, in the orchid family, blue is an unusual colour, and the Queen of Sheba has blue, and also pink. It has spots; it has stripes. It is really fantastic.

So, this orchid is very special and it is only found in Western Australia. The Queen of Sheba is rare and needs our protection.

What threats do orchids face?

Historically, habitat loss and fragmentation has had a massive impact on orchids in Australia, a reason why many orchids are mostly found in protected areas today.

The second major threat to orchids is disturbance, and a key disturbance for Australian ground orchids is the change of fire regimes. This is because many terrestrial Australian orchids have adapted to seasonality where the plants go dormant in the hot summer with little precipitation and they sprout and reproduce during the cooler winter months.

Now, with preventing big fires, the fire regimes are often scheduled in the phase where orchids need to come out and reproduce. So, it is really important for the conservation of orchids to be very careful about when those fire regimes are scheduled. And then, of course, feral animals are a problem because of trampling and foraging.

Finally, weeds are an issue because orchids are quite weak competitors and are shaded out very quickly; they are not competitive if there are large plants growing around them.

Do you know some good national parks to go looking for orchids?

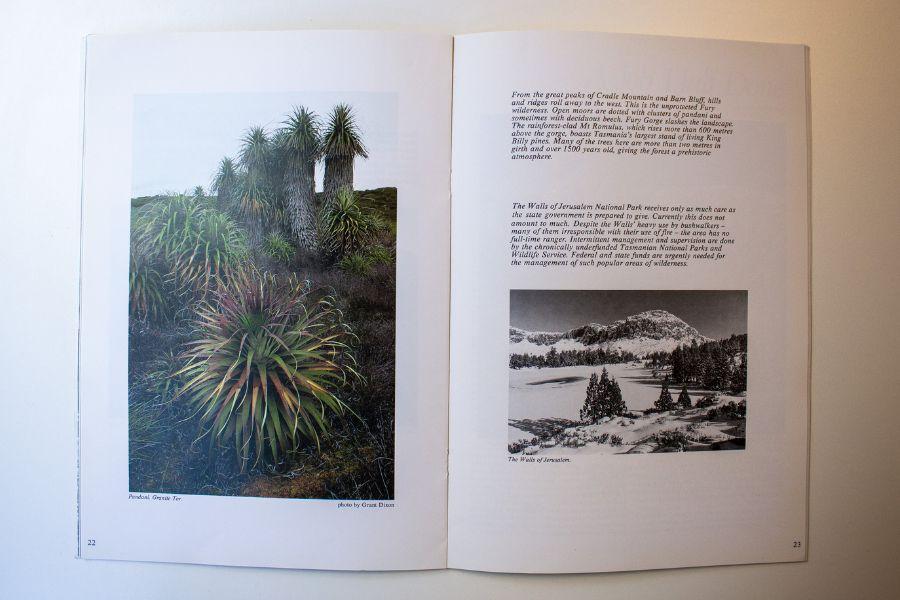

In the Australian Wet Tropics, Dinden National Park near Cairns is a really fantastic place. There you can hike to Kahlpahlim Rock, an outcrop that overlooks the rainforest. And while it's usually not so easy to see epiphytic orchids in a rainforest because they are high in the treetops, as you walk up to Kahlpahlim Rock, the vegetation gets lower and lower and you get into the zone where it's always moist. And then suddenly the epiphytes appear lower on the trees.

So, you have a good chance of spotting plenty of stunning Australian epiphytic orchids. And when you are on Kahlpahlim Rock itself, this rock dome, there's a huge population of rock orchids (Dendrobium speciosum), which is very rewarding to see in flower.

Director Ollie Ritchie crafted this work especially for Wilderness Journal, captured atop the epic sandstone cliffs of Bondi.

What is your background and what is your role at the University of Melbourne?

I am a Barkandji woman with Afghan, Irish and English heritage also. Like many in Australia, I am a result of the merging of many cultures and peoples. I am very proud of all of my heritage and very honoured to be an Aboriginal woman who has the opportunity to incorporate my love and pride in my people and my culture into my work. My Country is in western New South Wales. I have family ties to Broken Hill and Menindee mostly, with many of my family now living in Sydney also. I have always been a visitor to my Country and did not grow up there. This limits my cultural knowledge greatly, but I am always learning and this will be a lifelong commitment for me. I am so happy to be able to take others along on this journey through my work.

I came to study late in life after several different careers. In my current role at the University of Melbourne I am a Research Fellow with the Clean Air Urban Landscapes Hub, which is funded by the National Environmental Science Program. My research centres around Aboriginal perspectives of biodiversity in urban areas. I am also on the Indigenous Advisory to the Science Faculty and I work as a freelance writer and consultant in my ‘spare time’.

Why did you decide to write Indigenous Plant Use? You mention there being a lack of Aboriginal culture and knowledge in our urban landscapes—is your book trying to address that?

I wrote the book as I was getting many enquiries from people who were wanting to start Indigenous gardens, especially those in educational settings.

People are so keen to connect with Indigenous culture and to learn more, but sometimes don’t know where to begin. I wanted to make something accessible that would work to complement the many gardens and greening initiatives popping up.

My booklet is trying to help people to understand the depth of scientific knowledge evidenced in our vast knowledge of plants. It hopefully opens a door for people to continue their learning journey, to connect with Country and to be encouraged to know whose Country they are on.

What range of indigenous plants do you cover and from which Aboriginal cultures?

The booklet is limited to Kulin Nation plants as it came out of a project we did called ‘The Living Pavilion’ at the University of Melbourne in 2019. The Kulin Nation is the wider confederacy of Aboriginal groups across eastern Victoria. There was also a community garden at The Living Pavilion that celebrated the diverse Melbourne University Aboriginal community by featuring plants from all over Australia.

So, many of the plants are found all over Victoria (with many also common to south-eastern Australian more broadly) but there are also many from other parts of Australia especially chosen as they adapt well to temperate climates. Another wide-reaching aspect of the book is the many resources in the back for those wanting to learn more. There are podcast links and a huge array of resources mentioned to help people on their learning journey.

In what ways can indigenous plants provide a window into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and scientific practice?

The absolutely ingenious way our mobs have used plants helps people to understand our knowledge as science. For too long, our culture and practices, honed over the longest time imaginable, have been seen as ‘lesser’ by western science.

In its essence, science is careful observation and that is what we as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been using to develop knowledge and innovate. Our plants have been used in so many ways which have been integral to our ability to adapt and survive massive climatic shifts. They have been central to our survival.

"In its essence, science is careful observation and that is what we as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have been using to develop knowledge and innovate."

Zena Cumpston

When people start to understand how diverse mobs across Australia have tested and experimented to make even the most poisonous plants viable as highly nutritious food it gets them on the path, I hope, of realising this knowledge and the ability to harness resources is not ‘lesser’ in any way. For too long our peoples have not been given the respect we deserve as innovators and knowledge holders.

I believe that when people have the opportunity to engage with our knowledge from our perspective, which is not tainted with well-worn and problematic narratives that attest this knowledge as ‘lost’ or ‘in the past’, they are enlightened and interested to learn more.

What makes indigenous plants a good choice for your everyday suburban garden? Are they generally easy to grow?

Indigenous plants are a wonderful choice as they provide so much benefit—importantly not just for humans. They do not require fertilisers, can be grown in harsh conditions, they require little water compared to many introduced plants. They provide ideal habitat, foods and corridors for travel for many native animals, as well as adding much beauty to the landscape.

My garden is a mix of indigenous and non-indigenous plants because I just haven’t met a plant I don’t like! I see the native plants in my garden as more beneficial to animals than the introduced plants just from the interactions I see with the naked eye—I notice the birds flock to my indigenous plants much more than the introduced ones, for example.

Indigenous plants are sometimes tricky to propagate but there are so many really reasonably priced indigenous nurseries across Australia I don’t see this as a problem. When you choose plants that have thrived and survived specifically on the Country you plant them on I see it as giving back to Country and actively caring for Country. Many councils have wonderful lists of plants specific to their area.

Knowing what belongs on your Country, where you live, helps you to connect and understand your place more meaningfully. Indigenous plants are so important for biodiversity and there are so many animals we are caring for when we ensure our gardens are biodiverse.

"Knowing what belongs on your Country, where you live, helps you to connect and understand your place more meaningfully."

Zena Cumpston

Why is it important that people take it upon themselves to gain an understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander knowledge and practices, and learn about the Country they are on?

For too long the burden of educating has fallen on Indigenous people. There are so many healthy ways forward for us in Australia, where we can work together to not only face the environmental challenges we must all grapple with, but also to address the inequities which see Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people grossly disadvantaged across so many areas.

We must work together and working together means we must address our past, which is very much a part of our present inequities. Learning about Indigenous knowledge and practices is a powerful form of truth-telling. There is so much wonderful information available nowadays—especially resources developed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples that give us opportunities to address some of the problematic narratives about us as people which continue to harm us today. I urge all Australians to engage with us through the resources and writings we have developed—learn from us and not about us.

We are so generous with our knowledge and culture and I would like people to accept that generosity with the acknowledgement that we all have a role to play in addressing inequities and injustices by educating ourselves and finding a common ground from which to join together.

Educating people all of the time is exhausting, my hope for the future is that people take a more active role in educating themselves through engaging with our self representation. Look for websites and books by Indigenous peoples, there are so many available nowadays!

Zena is sharing her book for free; download a copy.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.