Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the seventh issue of our Journal. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures.

Main image above: Michele Lockwood photographed by Andrew Kidman, @andrewkidman. Images and film by Michele Lockwood @regularwildcat unless stated otherwise.

Fast forward some 40 years, I am sitting watch outside a National Park with a motorbike crew from the Elephant Response Unit in remote Southern Sumatra when this memory comes shuttling back. While anticipating the arrival of the herd, the primordial sound of a wild bull elephant’s trumpet erupted through the night. The sound, like a sharp airhorn, blasted me back in time to that vision of myself immersed in the glowing screen, transporting out of urban mundanity via the television gateway into the wild Indonesian jungle. And now decades later, it came into fruition—real-life me, physically alive and working with elephants in that very place.

September 11th was the catalyst for making the move to Australia. I felt an urgent need to escape the hypocrisy of America but never considered how difficult that transition to life in a foreign country would be. I found assimilation challenging; I couldn’t find work or make real friends and so low-grade depression set in. Everyday life without my connection to home and all the things that I thought defined me took a toll on my mental health. Something was still missing.

Some years passed, my children grew, and I was able to look outside myself for the first time in a while. Birds were a great initial distraction. Being surrounded by so much diversity made observation effortless. I kept a species list and attempted to imitate their songs, observed their flight patterns, learned their sexual dimorphisms. I came to know who they were by how their silhouettes moved in the trees and noticed their preferences for certain materials when it came time for nest building. I could tell when a goanna was about by the cacophony and chaos its presence would incite. My loneliness displaced as this connection to the Country I was on deepened.

I began to meditate. My awareness of the shift in planetary health became a prominent concern. I had a keen desire to devote the second half of my life to serving Mother Earth. I’d sit for longer periods and opened myself up to receiving direction on how best to do this. The answer was that I’d need to learn. I’d need to formalise my intentions. So, at the age of 42, after spending a lifetime in the Arts, I went to university and studied Environmental Science.

Night has fallen now. Wollumbin is in silhouette with the Moon high above in a waning sliver. Stars project their light through punctured holes in the ether as frog song echoes up from the creek. The wing beats from flying foxes are overhead, dispersing their pungent smell as they go. I live in the opposite hemisphere from where I was born, many time zones away, but the city that never sleeps still runs strong through my veins. New York City has informed my character in as many ways as Australia has tested it, and for both I am grateful.

It’s Australia; it’s hot and it’s dry, so if you don’t come up with any techniques to cope with that, the climate can be pretty hard to manage. Being nocturnal is a great way of managing in harsher climates. For most nocturnal animals, they come out at night because it’s the coolest time to come out. There are three categories of animals—there are diurnal animals who are active by day, like us humans. There are nocturnal animals that exclusively come out at night, and then you have crepuscular animals where they are most active at dawn and dusk. Lots of species we know and love or think of as nocturnal are actually crepuscular.

"Habitat has a huge impact on the number of nocturnal animals, including factors like the amount of forest areas, or the heat. You’ll find the highest proportion of nocturnal animals in areas like Central Australia where the habitat is severe and the animals need to be nocturnal to survive.

"Turn your lights out earlier if you can, and you might just be surprised by who you find in your garden."

"My favourite animal would have to be the bilby. They have two fascinating features that amaze me. When they run, they zig-zag or serpentine. When a bird of prey is hunting, it will drop just ahead of its prey and the prey runs into its talons, but because bilbies change direction all the time, they’ll often miss a bilby, which will make it back to its burrow. The second is the fact that their ears deflate overnight. Bilbies have no fur on their ears so the blood vessels are close to the surface and they thermoregulate. Bilbies lose all their heat through their ears, so if they deflate them they don’t lose as much heat while they’re sleeping.

"One problem nocturnal animals face is we light up so much of our cities: we light up our driveways and our gardens, and the animals need it to be dark. Turn your lights out earlier if you can, and you might just be surprised by who you find in your garden."

My spirit comes from the River. E made me. E, not he or she but E. E has given me strength, resilience and identity. The foundation to be strong and to keep Em strong.

We have a saying: ‘waiting time’—you cannot ask for something, it will come to you when it is meant to. I was told something, something I didn’t know I needed to hear. I was told by an elder that we are currently living in human form, a form that has the ability to look after Country. As we move through our other forms we may not have this ability, but we will remain here living on Country.

This taught me to use this life to care for Country, the place our ancestors live as well as our descendants. Each of us living our different lives have been given different experiences and tools to do our part. For myself I had studied multiple degrees and worked in a lot of industries, however, it was not until these past 12 months that I discovered one of my skills sets is filmmaking. More specifically film making for Country. Creating films to share the value of Country and create a feeling in those who have not yet felt the connection. To communicate First Law and the guiding principles for human-beings to develop their relationship with non-human beings.

I share this film, as our Living Waters sing out for hope, an evaluation and a revolution. We ask you, as a human being, to get to know the Country you live on, the people who have nurtured it, and to select an animal or plant that you will care for as a lifelong project.

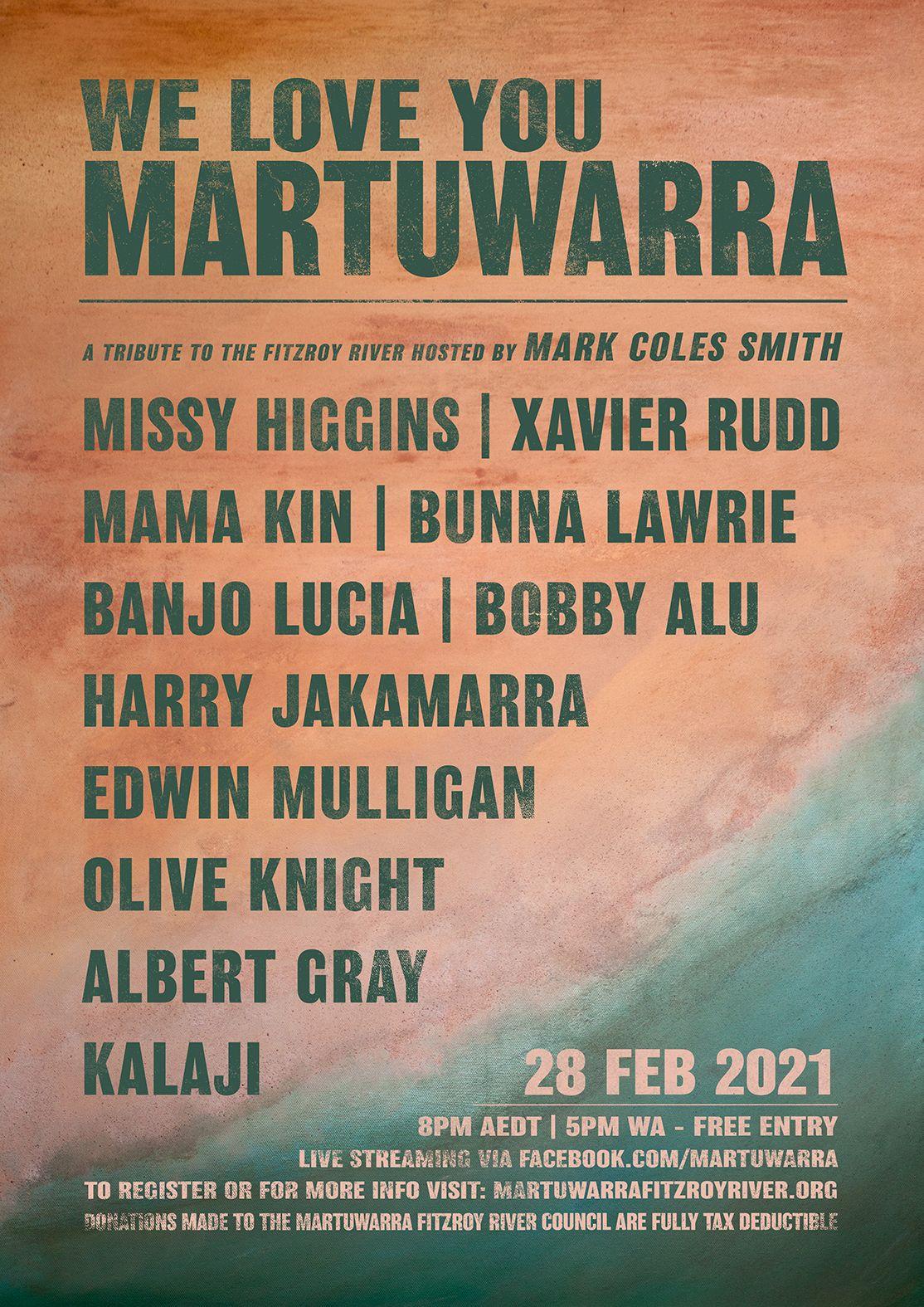

Our Living Water is singing out for hope as the Western Australian government is allowing fracking. The government understands the risks, they have chosen to ban fracking in ninety-eight percent of the State, but there is no protection for the Canning Basin. As the Living Water sings out for hope, we must respond. E invites you to strengthen your relationship with Martuwarra (Fitzroy River) the life force of the Kimberley. Celebrate E with us on the 28th February 2021 as our friends of the Martuwarra sing for Country.

What is it about fungi that you find inspiring?

When you start photographing fungi, you discover its huge variety. I probably knew that a fungus wasn't a plant, but that was about it; then as you get to know more about fungi, you start to realise that you're looking at an entire kingdom of life.

Plants, animals and fungi are the three major multi-celled kingdoms of life on land, and you can't really say that one dominates the other. If you think about the amount we know about plants and animals and then the amount we know about fungi, it's almost nothing. I think we've documented somewhere between one and two hundred thousand species, but estimates suggest there may be around four million species of fungus. So we've got a long way to go.

So there's incredible variety. It's never-ending; the more I get into it, the more I realise there is to discover.

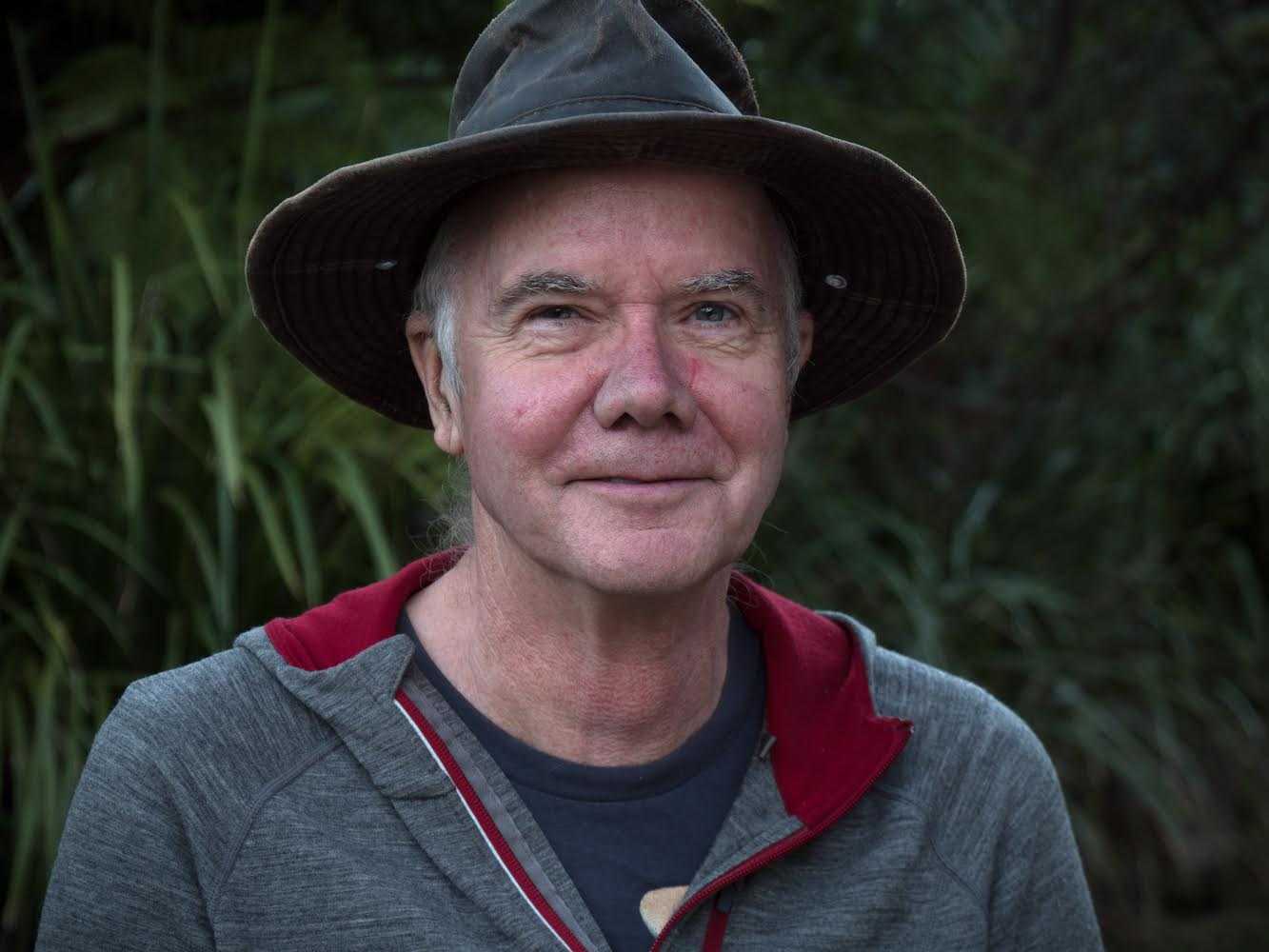

How did you get into photographing fungi?

I had worked in IT for 30 years or so. I’d never had very much to do with photography until about 2000 when on a whim I bought a little digital camera. It was a beautiful little camera; it didn’t have a zoom on it, but it took nice little pictures.

Later, I discovered mushrooms.

I retired and ended up coming to Northern Rivers, NSW, and it turns out that this is actually a hotspot for fungi. There’s plenty of rainfall, which means plenty of fungi. The other place I go to find mushrooms is the west coast of Tasmania from April to May. The forests there are very predictable in autumn; you will get mushrooms, lots of mushrooms. The same goes for the Tarkine and wet forests on the East coast of Tasmania too.

I started shooting fungi, building a gallery and experimenting with timelapse, and I ended up supplying the BBC with timelapse footage of the bioluminescent fungi we have in the Northern Rivers for the Attenborough documentary Planet Earth II.

At around the same time, the Kunming Institute of Botany in China asked if I would like to help them document fungi in Yunnan. That was 2015, and since then I've been out to Yunnan almost every year cataloguing the unusual fungi found in the region.

What evolutionary benefits are there for mushrooms to often be so colourful?

It's been commented that there are a lot more brightly coloured fungi in rainforests than there are out in fields and grasslands. The bright colour could occur in rainforests because there's not a lot of wind, so spreading spores by just dropping them and letting the wind carry them is not nearly as effective.

A lot of rainforest fungi and fungi in general are spread by insects eating the fungus and then spreading the spores. And insects generally have very good colour vision, they can see vastly more colours than we can, so the fungus uses the colour to signal to insects and other animals to eat it.

Fungi have some unusual life cycles. What are some of the most extraordinary?

There are fungi that live as an endophyte, a microscopic fungi inside the cellular structure of plants. Like the hundreds of thousands of different species of gut bacteria that we live symbiotically with, plants live symbiotically with fungi in their cellular structure.

Some of these fungi provide different chemicals. One that we know a little bit about is paclitaxel, used as a chemotherapy drug that is extracted from the Pacific yew tree. You may have heard of it as the brand name Taxol. But the actual paclitaxel is produced by a fungus within the tree. The yew tree will use it as protection against predators, so insects that try and eat the yew will be poisoned by the paclitaxel.

There are lots of lots of examples of this where fungus, which is a brilliant little chemical factory, produces chemicals that the plants use as toxins or for other purposes. We don't know most of them.

If the tree dies or a branch falls, the fungus that was living in the tree can transform into a macro fungus that will consume the remaining dead matter, recycle it and then come out as mushrooms; a totally different form. It goes from a single-celled organism to a multi-celled organism. But it’s not like a butterfly that emerges from a caterpillar, flies around and dies; the fungus can change from one form to the other, then back to the first one again. Fungi can have different modes of existence depending on the circumstances.

Is it easy to spot luminous fungi?

For most luminous fungi, you can turn your torch off, and if it's a moonless night you'll see the fungi quite easily. For some species, you have to turn your torch off and then wait for a minute so your eyes become acclimated to the dark. But for photography, that's not very much light at all and you'll need a 30-second exposure or maybe longer to capture it.

Why have some fungi developed bioluminescence?

It probably attracts insects to eat them. So certainly the luminous fungi seem to be very attractive to slugs and snails.

The bioluminescent family here are Mycena chlorophos; most of the time they'll be luminous, but sometimes they're not. So you can even get a stick where some of the mushrooms that grow on it are luminous and then another patch of them that aren’t. It can be frustrating!

What role do fungi play in the forest?

One is that they are the primary recyclers, saprobe fungi will break up any dead material and recycle the nutrients. Large fallen trees will be well rotted away after five years, and that's all due to fungus. Without it, forests would quickly be smothered by mountains of logs.

Another role is that played by the ectomycorrhizal fungi. About 10 percent of the tree species on Earth are dependent on fungus to assist them in getting nutrients and water. That 10 percent of trees includes all pines, eucalypts, oaks, ash and many more.

The fungus accesses minerals, particularly phosphorus and water, and the tree will photosynthesise at about double the rate when it has the ectomycorrhizal fungi, so it's a significant difference.

Then there are parasitic fungi that live on trees and insects. Parasitic fungi can just be freeloaders, but they can also serve a very useful purpose in controlling insects.

It has been said that all land plants rely on fungi in some way. We wouldn’t have forests without fungi. They play a critical role in ecosystems. Take, for instance, the relationship between the truffle and the Eastern bettong in the forests of Tasmania… The bettongs eat the truffles, a type of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Without the bettong, the fungus wouldn't be spread, so new trees that formed on the fringes of the forest wouldn't get the benefit of the fungus. The trees are totally reliant on the bettongs. But now the bettongs are being killed by feral foxes and cats.

What threats do fungi face?

The major threat is habitat loss, the wiping out of old-growth forests in particular. If a bushfire goes through, provided it doesn't happen too often, fungi can cope. But if it happens again before the forest recovers properly, then you just lose biodiversity. The same thing that affects the forest, will affect mushrooms. The protection of old-growth forests is very important for fungal diversity.

Watch Planet Fungi, a documentary charting Stephen Axford's expedition to catalogue the fungi species of North-East India.

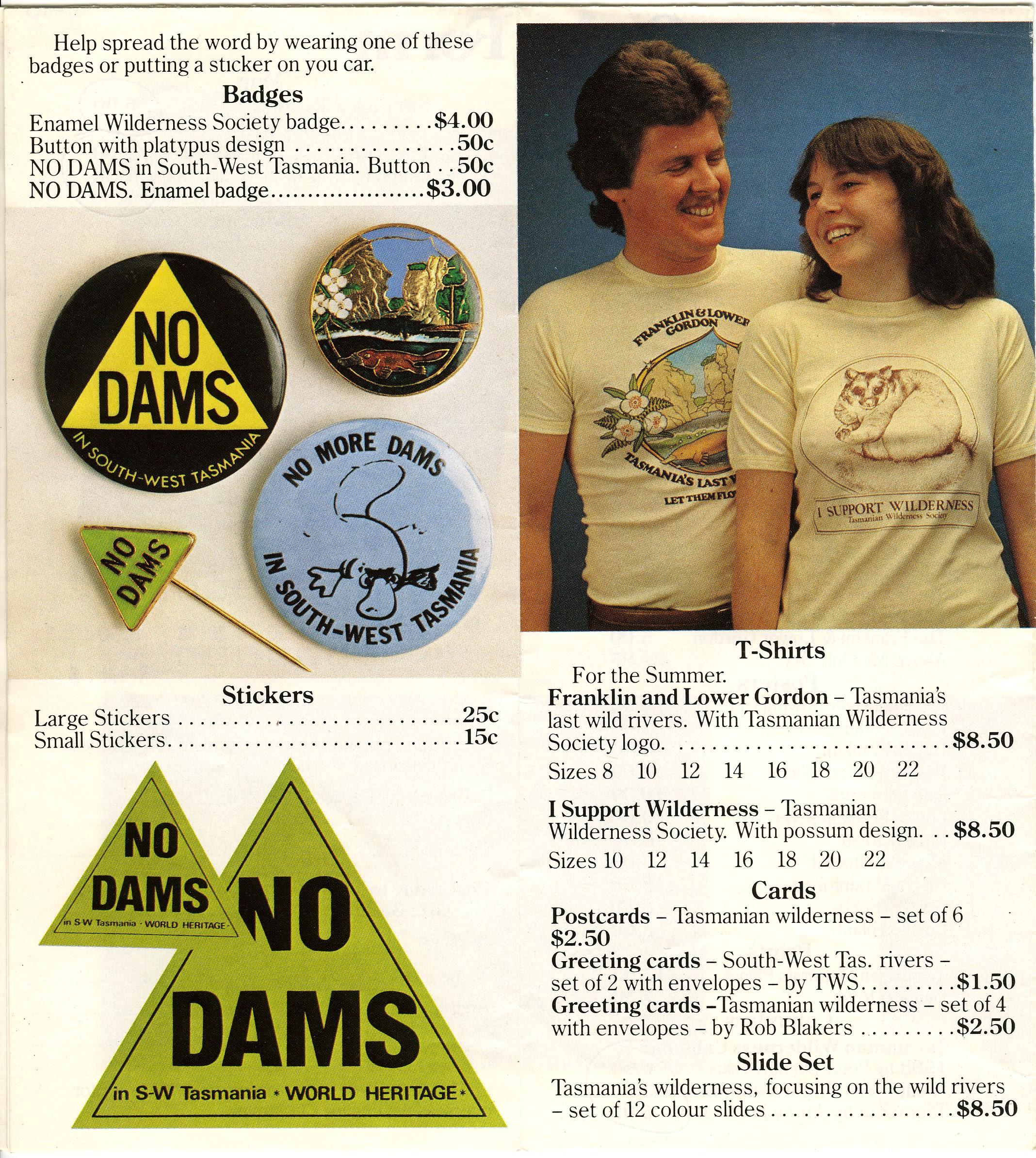

This is a limited-time offer from the vault. Only available in authentic '80s oatmeal organic colour. Order yours today.

P.S It doesn't have to be quite so tight...

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.