Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the eighth issue of our Journal Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures.

Without occupants, they're curious floppy sacks of matted, musky material; inanimate relics gathering dust in store cupboards around the country. But the privileged few who've worn the koala suits know them as anything but. In the 1990s their beady eyes were used to strike fear into politicians, while also melting the hearts of passersby to give what they could in a time when small change was a thing.

Someone who's used to photographing icons is Andrew Cowen, winner of the National Photographic Portrait Prize. Take a look at his photos of a Wilderness Society icon, while the heroes who've been behind the (fluffy) mask talk of the heat, the discomfort, but ultimately the glory of donning the koala suits.

Dr Lani Sowerby Campbell, Lecturer in Disability and Evidence-based medicine, University of Sydney:

"It was from about 1988 to 1992 that I spent some time in a koala suit, collecting donations for the Wilderness Society with a big bucket outside Town Hall in Sydney's CBD. Children, little boys, used to run up and hit me, and you can't turn too well in the suits to defend yourself as the head is quite big.

"They were smelly and always hot, there was a stench of the people that had gone before. In fact I could pretty much conjure who had been in the suit before me.

"Asking for money is never easy, but the suit offered you a form of protection, you felt empowered to ask as you were hidden; you could still hold a conversation, albeit somewhat muffled.

"And the money you did receive you had to hang on to for dear life—people would try and snatch the bucket from your sweaty koala mitts.

"I am a proud member of the Wilderness Society today, but I'm also able to brag that I used to wear one of the koala suits, an extra medal of honour I have over others!"

Marlon Porter, Fundraising & Engagement Officer, the Wilderness Society:

"Wearing the koala suits had a few hit or miss freshness factors, such as who wore the suit last and in what temperature or season the costume was having to be endured in, or when the suit was last washed. Selecting which particular suit to wear was a full-sensory affair!

"It was nice to enjoy some level of anonymity in the suit, which also lent itself to one's ability to inhabit and assume the spirit of the Koala. There was a certain street warrior code and nobility that came with it.

"I remember (fuzzily), in about 1993, I was working on the streets of Sydney in an area very close to the Chinatown markets. A restaurant/hotel/casino had its front door open inviting folks to waltz in and have a go at karaoke.

"I noticed a few tunes by the legendary Roy Orbison. We had an internal giggle over the funny juxtaposition of an iconic native Australian marsupial singing the classic song from Blue Velvet about a "candy-coloured clown they call the sandman..." tip-toeing "to my room every night", which was more than enough motivation to get up and have a go.

"It turned out the performance must have been entertaining as the bucket seemed to be a whole lot heavier on my wave goodbye!"

Eva Abbinga, @larissaandeva, Artist:

"I was a koala for about six months in 2000. I was a student and would wear the suit for the Wilderness Society around Brunswick St in Fitzroy.

"It was an empowering experience to wear one and I liked the anonymity of being a koala, but the mesh around the eyes was quite see-through and your cover could be blown with people going 'Hey, there's a girl under there!'

"Walking home one evening I do remember seeing a discarded koala suit, just laying in the street. I picked it up and took it back, but I was concerned for the former occupant!

"The suits were iconic, they were so 'Melbourne' back then—part of the fabric of the city."

With thanks to SUNSTUDIOS Sydney.

For more on koalas, view our guide to the threats they face and what you can do to help.

Wear a Wilderness Society koala suit with pride, without having to wear the actual thing! Photographer Andrew Cowen's portrait of the iconic koala suit is now available in this organic cotton t-shirt—in kids' sizes too!

These t-shirts are only available for order until 10 May, after which your order will be shipped. Money raised goes to help the work of the Wilderness Society. UPDATE: SOLD OUT.

We were visiting so often that we decided to buy a place of our own. After an elongated search we found a beautiful, unmolested piece of land in an area called Little Forest. It had beautiful big trees, almost totally pristine bush and a creek. It also had a simple converted shed to stay in that was off-grid with no phone or internet. There were wombats, lizards, snakes and lots of birds. The shed is right in the middle of the forest. The trees are less than ten metres away. It feels remote and secluded although it is not actually very far from the closest town.

Spending time there immediately connects you with nature. In a short time you tune into the sound of the air moving through the trees. Or the sound of a bird’s wings beating as it flies past. The noise of insects in summer can be intense and relentless. A thunderstorm echoes around in a way you never experience in the city. Being able to spend time there has been the perfect antidote to life in the city. We spend our days there concerned with when we are going for a walk, what we are going to eat and, if the weather is cool, when we are going to light the fire.

On December 31 2019, what is known as the Currowan bushfire went right through our land. Every single tree was burnt. By some miracle our shed was not destroyed and sustained relatively minor damage. Many houses in the area were destroyed, there was a huge amount of damage to rural properties and several lives were lost. The cost to the natural environment was immeasurable.

The impact of seeing our beautiful land transformed in this way was huge. The first time we visited to assess the damage I could barely recognize the landscape as we drove in. The bush in this area is usually very dense. Suddenly I could clearly see into spaces I had never seen before. The forest became skeletal in form. It was like a body with all the flesh removed. It was also a totally different colour palette. It was as if someone had dialled out the colour leaving only brown and black. It was also silent. The forest is usually full of the sound of leaves rustling, creatures moving on the ground and birds. Now there were no living things anywhere. After a few hours I was elated to see a tiny lizard moving on the ground. Being there on that first day was an intense experience and our loss was minor compared with what other people went through. We made a list of needed repairs. Our shed had some damage, we had no water and there were lots of severely burnt trees that needed to be cut down.

@cowenandrew andrewcowen.com.au

Antechinuses’ short lives are a brutal, fundamental expression of nature that has long-intrigued scientists. We spoke with mammalogist Dr Andrew Baker from the Queensland University of Technology about his work with these tiny marsupials, why their frenetic mating regime leaves them vulnerable to our shifting climate, and why they could hold the key to human ageing.

I work in environmental science and biology. My research is focussed on the discovery, description, ecology, taxonomy and conservation of mammals, but more broadly, I work on genetics and the evolution of a range of mammals, including antechinus.

Antechinus are part of a group called dasyurids, the carnivorous marsupials. There are about 74 or so species of dasyurids in Australia including quolls and Tasmanian devils. But there's a whole heap of smaller dasyurids as well, and antechinus are one genus of those, consisting of about 15 different species.

Antechinus are different again from most of those other dasyurids because their sex lives are fairly unique: they are what are called semelparous breeders, which means every year the males all die after breeding. And that kind of sets antechinus and a few of those other types of dasyurids apart, not just from other Australian mammals, but most other mammal groups worldwide.

There were 10 species of antechinus in about 2010. And my team has added five more to that group. And alarmingly, of those five species, probably four of them need protecting and two of them have been listed federally in 2018 as endangered.

We looked at one species of antechinus and found evidence of a new one and then more popped up!

They are a lot of fun to work on because they don't really have overlapping generations and they breed at the same time every year, so for a field ecologist like myself, that takes some of the challenges out of who's who and where they came from and so on.

There are lots of mammals that are more or less shades of brown. In fact, small mammals are often called 'LBJs' or little brown jobs. Part of the reason for that is they have got a very well-honed sense of smell rather than sight, and they're often nocturnal, so there's probably less selective pressure on being different colours in a lot of cases compared to birds for example.

Some of these mammals are pretty small, mouse or rat-sized, and live pretty cryptic lives, which brings some challenges with trying to find them. I like antechinus because you actually can tell them apart by their colour; it's subtle, but the colours are notably different for most species.

I kind of like that about them. It really is such an extreme lifestyle: you go from being at the prime of your life as a male antechinus, at your maximum weight and health at about 11 months old, and then two weeks later you're dead.

Both the males and females get incredibly stressed during the two-week mating period. And that's partly due to the fact that it's so vigorous and ferocious that breeding bouts can last up to 14 hours. On top of that, the females are trying to get away to mate promiscuously with as many males as possible. And the males are often trying to beat off other males, and they're also trying to hold the females once they've got them. It's this big melting pot of frenzied sex.

Everything is at stake, and for the males it's their shot, they've only got two weeks. For the females, the promiscuous breeding ensures that most females have got sperm from numerous males and sometimes numerous fathers can make up a litter of babies from a single female. That's the norm. It also ensures that nearly every female is pregnant; it would be close to one hundred percent in a lot of populations at the end of the breeding season.

Some of my colleagues have found that it's also about sexual selection. The females select for bigger, stronger males. That means the males get bigger and stronger, and they get bigger and bigger testes because the more sperm they have, the more vigorously they can impregnate females.

With the males this has reached a point that sperm are fully developed prior to breeding. Most animals, including humans, have got sperm at various stages of development, but before the breeding season, antechinus males have a full complement of fully developed sperm. It means that they can devote all their time to mating with females, even eschewing most food during that two-week period.

The mating season stresses both males and females. They're both producing stress hormone, cortisol, and the males die because part of the consequence of having really large testes, is they've got a lot of testosterone. And in fact, for their body size, the amount of testosterone produced is so great that it eventually stops the mechanism working that turns off the cortisol stress hormone. They then get these floods of free, unbound cortisol surging through their systems.

Across a period of days, unflagging cortisol production is poisonous. It causes their organs to malfunction leading to internal and external bleeding. They can't heal themselves because they effectively have massive immune system failure. In the last week of the breeding period, they get huge parasite loads of ticks and mites that their bodies can't get rid of. In the end they usually die from blood loss or internal bleeding.

It's fascinating and weird. It's possibly even more fascinating for the females because they've gone through all the rigours of the two-week mating period, and then a month later they give birth to anywhere between four and 14 young depending on the species. Each night, they end up having to eat up to half their body weight just to produce enough milk to satisfy their rapidly growing brood.

It's no wonder that relatively few females actually make it through to the next breeding season.

We're working with a big collaboration of people internationally looking at the full spectrum from really big, really old mammals like bowhead whales that might be hundreds of years old, to really small, fast living things like antechinus. And it's looking at all those genomes and how the genes affect the body tissues. You can then relate that to human ageing to see if similar genes might be responsible for the onset of ageing.

It's good to be a geneticist at the moment, because I think there's going to be a lot of exciting things happening in the next decade.

It's the usual suspects: climate change, land clearing and the introduction of cattle, horses and pigs, which trample habitat, and predation by cats and foxes.

The antechinus that live in high, wet areas are under particular pressure. Those regions are diminishing both because of habitat fragmentation and the climate warming and drying. So anything that likes high, undisturbed, wet habitat in Australia is in for a rough time. There are a couple of these rare antechinuses that fall into that category.

One is the black-footed dusky antechinus found in the Scenic Rim. There is increasing evidence to suggest that they seem to be following the moisture, which is retracting altitudinally. A lot of the cloud forest in the Scenic Rim on the border between New South Wales and Queensland has reduced in size.

People forget that the 2019–20 fires came on the back of 12 to 18 months of drought. That's one of the reasons the whole eastern seaboard went up like a torch. A lot of the small mammal populations were struggling before the fires and continue to struggle even if those areas haven't been burned. The bigger picture of those fires is that it's not just the areas that were burned that are a cause for concern; it's also the areas that were prone to burning because of the drought.

Antechinus rely on predominantly insects and spiders for food. And entomologists around the world are lamenting the loss of invertebrates. When you couple that with a drought and then treble it with fire, you've got a big problem for the animals that survive. They are then prone to predation from cats because their habitat has been removed and they've got nothing to eat.

We've actually been monitoring those populations in and around Springbrook and Lamington National Parks for the last three or four years, before and during the big drought. We've noticed that it's not just the number of threatened black-footed dusky antechinus that has decreased, but other small mammals in the area have declined up to tenfold. That includes the more common brown antechinus and also two native rodents, a bush rat and a mosaic-tailed rat.

When you see something like that, it suggests that what's happening is at a broad scale across the food web. It'd be worse if it had burned for sure, but it's dire already.

Last year, the black-footed dusky antechinus hadn't bounced back. We still haven't caught one up there for three years. So we have to wait and see what happens; we will go back up this year and have a look.

I think they are there because we've got dog detection teams, and the dogs have detected them every year. However, there are fewer and fewer dog detections.

We've got camera traps and live traps. We haven't caught them in a live trap for three years and they're much less detectable on cameras as well. So everything is pointing towards a big reduction in the numbers.

But if we didn't have the dog detections, I'd be crying into my beer.

It's not great. Fortunately, one of the places we went was Bulburin National Park, looking for the silver-headed antechinus. They are in habitat that was previously drought affected and burned, and at a couple of burned sites we actually caught some! I wasn't really expecting that and it shows there is some resilience.

Animals like this have evolved within a fire-prone continent for a long period of time, and that gives them a base level of resilience. But the problem is the rate at which the change is happening. Animals like antechinus aren't able to handle this rate of change.

No, I think it harms them. If I had to sit down and design a sex life, I wouldn't come up with that. It's not good because every year all the males drop dead; for a period you've halved the adult population. While that creates more available food for females who are gestating young, it puts tremendous pressure on females, because if they die and that population blinks out, then that whole group of animals is gone. There's no juveniles coming through. That's it.

I always hope. But resources are limited, so we have to figure out what aspects of the animal's biology and distribution we're going to manage, and you can't do that unless there's continued support to monitor them.

With species conservation, it's sometimes not just a case of what's lost that we know is there, but it's what's potentially lost that we don't know is there. There's an example of that with the antechinus in fact. Over the last few years, work we’ve done suggests that the brown antechinus, which occurs across much of coastal eastern New South Wales, may in fact be two separate species. So the original species range is effectively halved, and many populations have been devastated by the 2020 bushfires.

That's probably true for a whole range of animals, not just mammals, but other vertebrates and sure enough, invertebrates.

What is currently thought to be one species can actually be composed of several species. And with these vast bushfires, we could lose species we're not even aware of.

Be interested. If more people join local groups and become involved in the environment and the animals and plants in it, the more connected we are, the more we're likely to care, and that becomes pressure on the people making the decisions. And on such decisions rests nothing less than the future of our environment, the threatened species living in it and, ultimately, ourselves.

All photographs, videos and text by William Gladstone. See more at @williamgladstonephotography

Prof William Gladstone has spent much of his life exploring and communicating the complexity and wonder of the ocean environment. Last year he retired from an academic career of teaching and research in marine biology at the University of Technology Sydney. "I've always had a passion for the ocean's bizarre lifeforms, the intricate ecosystems they inhabit; academia was just a different form of expression," says William.

Throughout his career he has been careful to infuse a sense of wonder in his teachings, something often lost behind data and the scientific method. He's now rechanneling that curiosity and awe through his photography, a coupling of science and beauty.

"It's a personal exploration of how best to communicate my love of the oceans. I'm trying to maintain an honesty about what I find so beautiful and fascinating," he says.

Below, some of his most intriguing images and the nature behind them.

Sand collar, sausage blubber, jelly snag, or shark poo?

It’s the egg sac of a moon snail. The tiny dots are the individual eggs. As the female lays the eggs she covers them with a jelly. The jelly absorbs water, transforms into a crescent-shaped life raft, and protects the baby moon snails until they hatch.

Life of Port Jackson sharks: The Cough

The eyes of fish have sphere-shaped lenses and they focus on objects by moving the lens backwards or forwards. We humans focus by changing the shape of our lenses. One edge of the lens of the right eye of this Sergeant Baker is visible in the photo. The coloured streaks are caused by the light from my flash reflecting from the back of her eyeball at different directions. The eyes of the Sergeant Baker give us a clue about their ecology. The eyes are large, relative to their body size, because they are visual predators. They strike upwards into schools of fish or pursue and chase down their prey. This is helped by their sleek, torpedo-shaped body.

Giant clams

Iridescence in the mantle of a Giant Clam is produced by specialist tissues and crystals called iridocytes, which act as nano-reflectors. The iridocytes direct sunlight of the optimal wavelength necessary for photosynthesis towards symbiotic microalgae living within the mantle tissue. Clams get most of their nutrition from the photosynthesis of the microalgae. The iridocytes also absorb damaging ultraviolet radiation, protecting the clam and the symbiotic microalgae. The colours and patterns in the mantle also protect Giant Clams, especially the smaller and more vulnerable juveniles, from predation. Mantle colours can match the background colours of coral reefs, providing some camouflage for the Giant Clam from predators who enjoy a meal of clam mantle.

Asleep: parrotfish

I photographed this sleeping parrotfish, wedged into a coral crevice, around midnight and was able to get close enough without disturbing it to capture the reflection of the flash in its eye. Sleeping fish resemble sleeping humans: their muscle tone relaxes, their heart rate drops, and they are much less responsive. And like humans (and other mammals, as well as birds and reptiles) the brain waves of fish change while they are sleeping, indicating fish go into a state of sleep that is very much like our REM or Rapid Eye Movement sleep state. It’s during the REM state that even though our body is immobile and asleep our brain is actively consolidating memories and dreaming. Many fish sleep from just after sunset to sunrise, and its benefits for fish must be greater than the great risks of predation while sleeping. The occurrence of an equivalent state of sleep in fish shows that the brain mechanisms responsible evolved more than 450 million years ago.

Noctiluca

Some of the greatest beauty in the ocean is produced by the smallest organisms. Red tides are caused by blooms of the marine plankton Noctiluca scintillans. Wind and waves have forced this bloom onto the beach near Hawks Nest (NSW). Since the 1980s Noctiluca has expanded its range around Australia, and red tide blooms are occurring more frequently and with greater intensity. Photographed from a helicopter at a height of 500 feet.

Beautiful gills

Gill slits, red feather-like gill filaments, and the gill arches supporting the gill filaments of a Port Jackson shark. While resting on the seafloor, muscles in the Port Jackson shark’s throat pump seawater into its mouth. The water travels across the filaments where oxygen is extracted, and then leaves through the gill slits. I took the photo from behind the shark while I was laying on the sand, at the moment the gill slits were fully open as seawater was being expelled.

The teeth of the Port Jackson shark

Looking closely, I find the teeth of Port Jackson sharks beautiful and fascinating. Port Jackson sharks have two types of teeth: pointed, grasping teeth at the front of their jaws, and crushing molar-like teeth at the back. Because they can catch, hold, pierce, shatter and crush, Port Jacksons can eat many different types of prey. Their teeth change throughout their lives, and so does their diet. While the jaws of young juveniles have many pointed, grasping teeth, the number and size of crushing teeth increases as they get older. Young juveniles eat worms, crabs and some molluscs. Sub-adults eat more hermit crabs and eels. As well as crabs and worms, adults eat flatfish, squid and octopus.

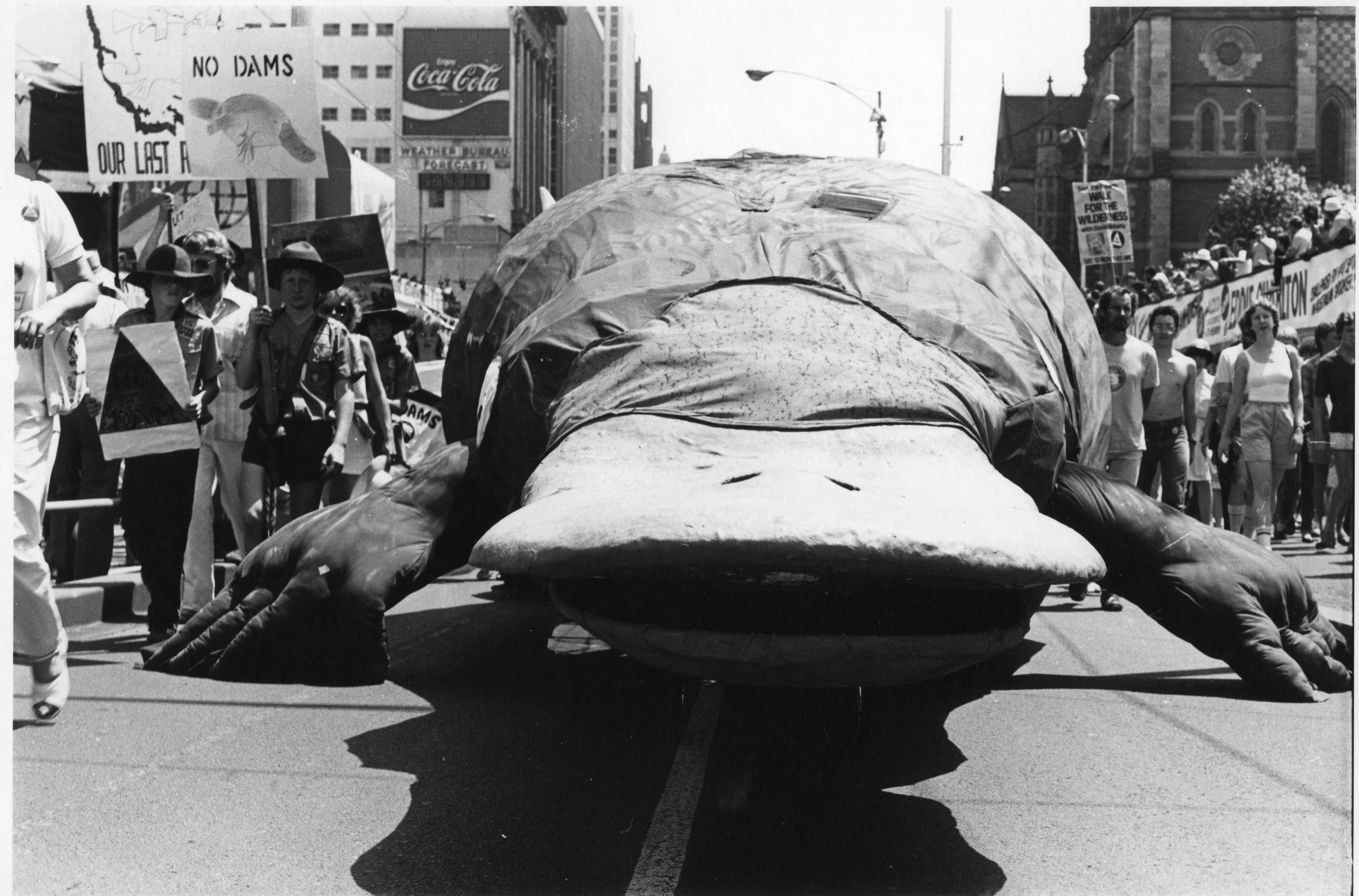

A giant platypus takes to the streets of Melbourne as part of a protest against the Franklin River dam. 15,000 people took part in the march on 13 November,

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.