Wilderness Journal #030

This edition we focus on the lands of the Mirning people, the vast limestone Nullarbor Plain that merges with the waters of the Great Australian Bight. We thank the Mirning for sharing their world with us.

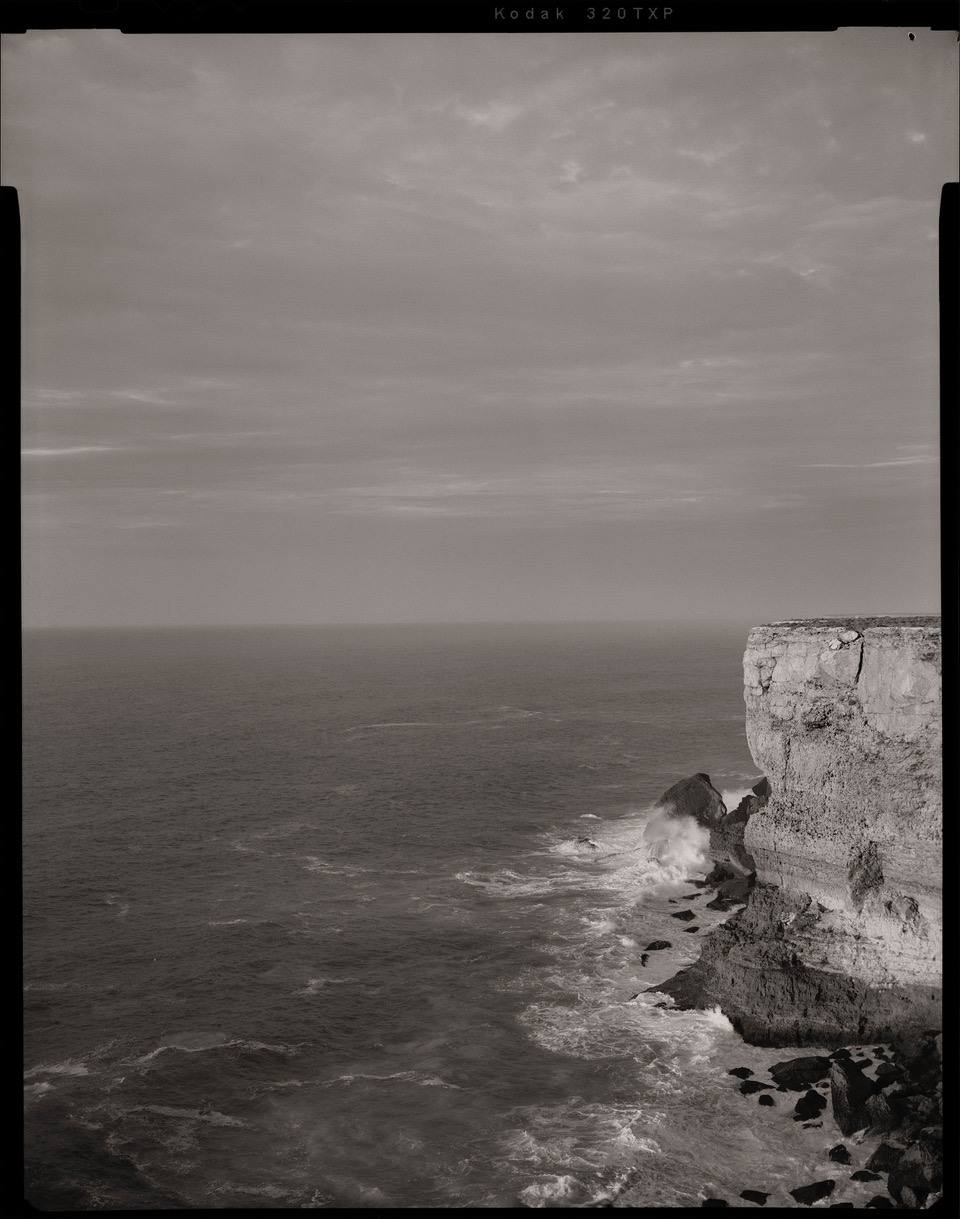

On a recent journey across the Nullarbor, photographer Ingvar Kenne captured epic space, beauty and the connection of land and sea for Wilderness Journal. Main image above: The Southern Ocean and Nullarbor Plain.

About 800km northwest from the Kaurna people’s traditional land of the Adelaide Plains is Wurlala, Wallala Rock. Mirning Senior Elder, Aunty Dorcas Miller, was taken here as a child by tribal elders to receive teachings on the boundaries of Mirning Country. With her back to the Gawler Ranges, open arms and an open heart, she welcomed us to everything to the west—the ancient seabed land of small trees. I was struck by how distinct this vast country is when viewed from the rocky outcrop.

A few hours later, we arrived at Yerlada, the coastal town of Fowlers Bay, to be greeted by the most spectacular sunset across the Great Australian Bight, a place Aunty Dorcas calls the Gateway to the Galaxy.

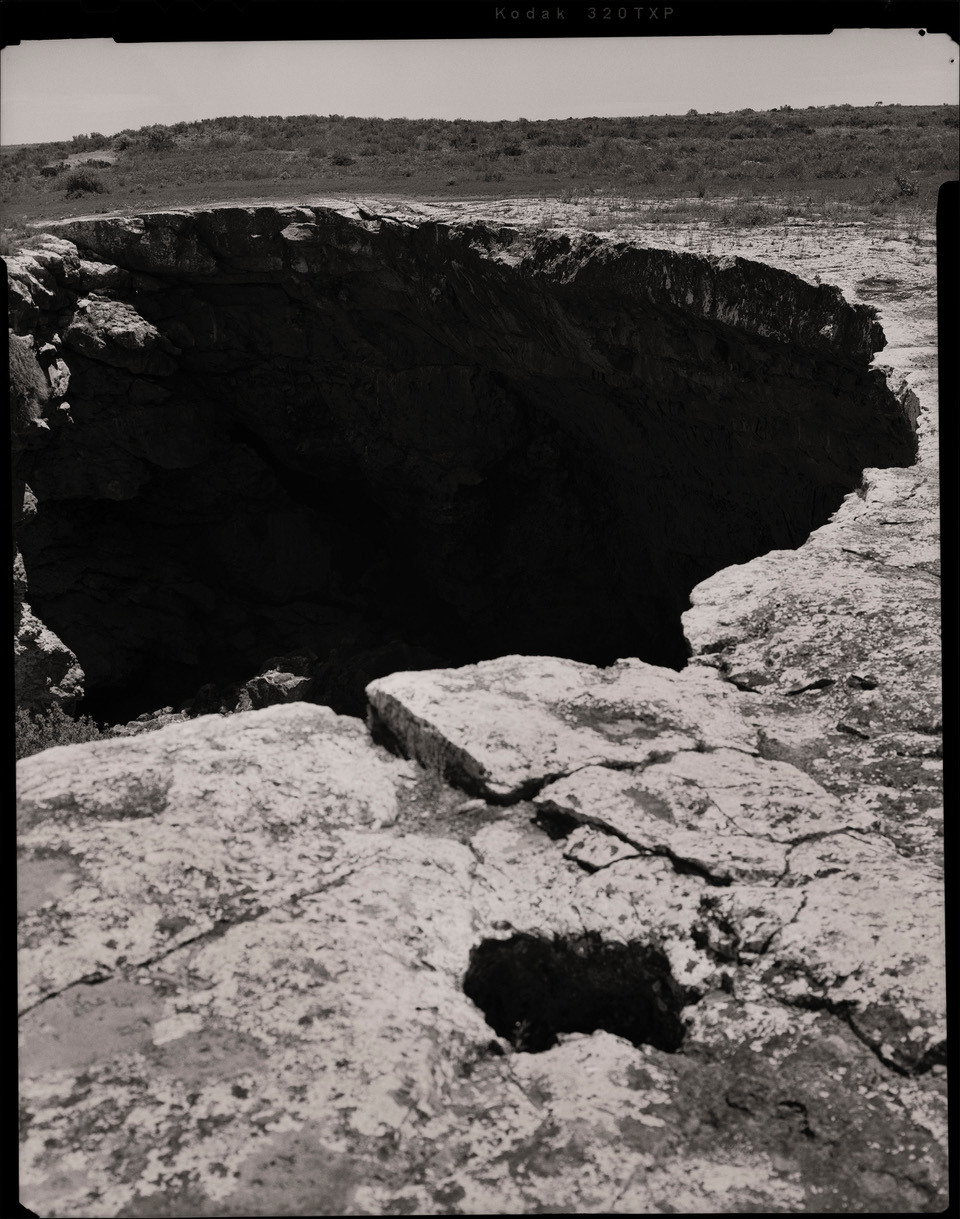

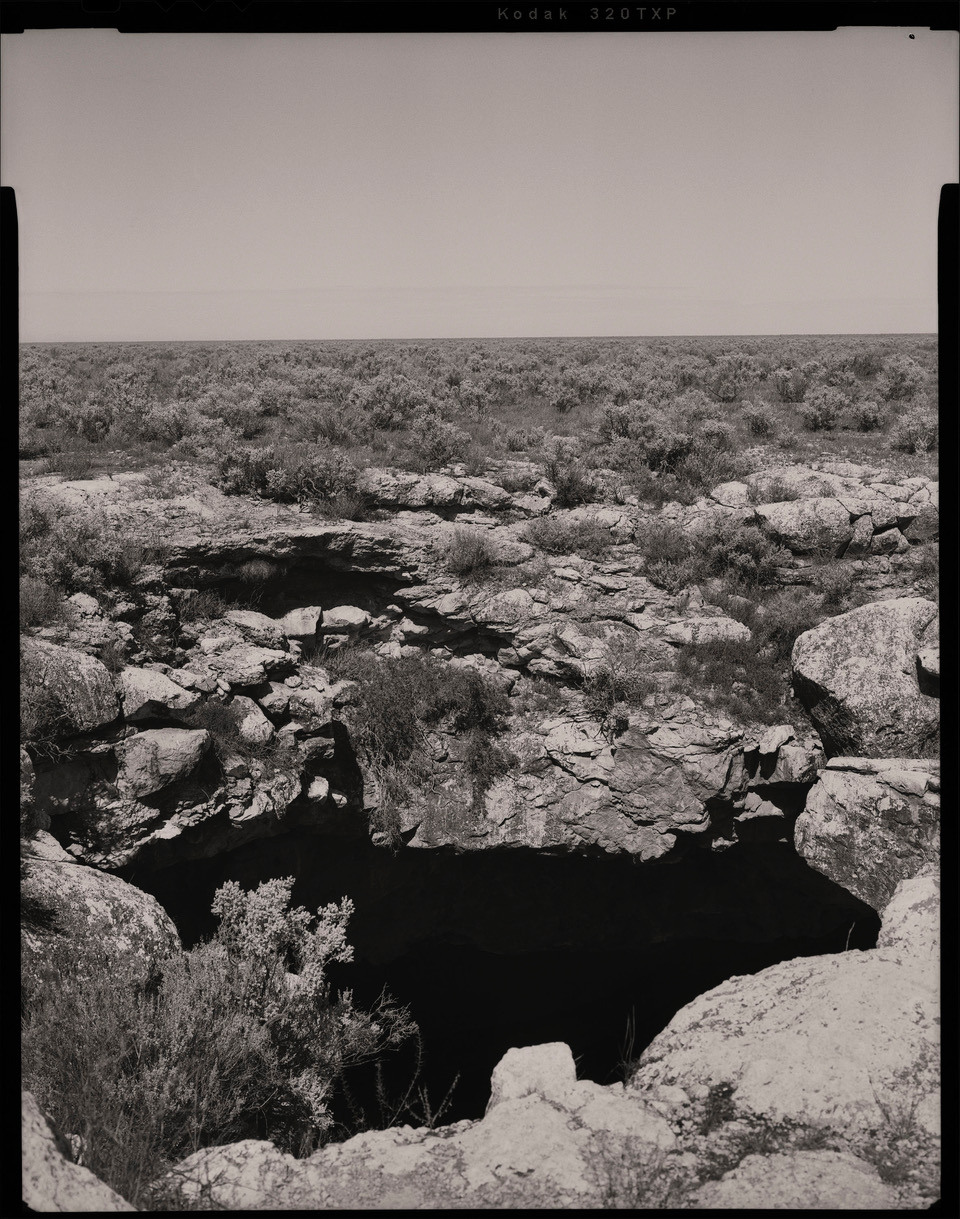

The next morning, after a hearty breakfast of chatter, our convoy continued west, under the beginningless skies of the Nullarbor Plain. Turning off the highway, we were guided down a long limestone track by a welcoming party of shingleback lizards to the Murrawiginie Caves.

Mirning Senior Elder and Whale Songman, Uncle Bunna Lawrie, led the men into a cave, where he told of the incredible continuity spanning tens of thousands of years. He spoke of a welcoming and a blessing. Upon making our way back to the surface, we discovered a cloud had rained just upon the cave, leaving everywhere else untouched. Uncle Bunna spoke not only of a welcoming, but also of a cleansing.

Two black tiger snakes had also made their relaxed presence known at the surface, acknowledging the arrival of Mirning family. These caves are notorious for tourists being scared off by snakes, recognised as cave protectors by the Mirning.

We then travelled to Koonalda Cave, some hours deeper into the Nullarbor system. This is one of the most important men’s whale dreaming sites in the limestone country. Upon arrival, Uncle Bunna and the Elders appeared quietly traumatised, spiritually hurting by the recent desecration evident at the cave’s entrance. Large boulders had collapsed into the cave where there used to be a steel fence with gate and at its edge, new green plastic matting and a staircase drilled into the fragile limestone replacing the majestic approach.

This is supposed to be the foremost heritage site in South Australia, one that changed the text book understanding of the length of Aboriginal presence in Australia. It is also in the middle of the Nullarbor Wilderness Protection Area. Such desecration has to be addressed.

Then south to the coast and Ngargangurie, the iconic Bunda Cliffs, where the Nullarbor Plain meets the billiam, ocean of the Great Australian Bight. The Mirning do not see themselves as separate from land and sea country, separate from the animals or separate from the plants. This was on full display when a juvenile white bellied sea eagle glided down to greet us, literally hanging in the air at eye level above a backdrop of the cliffs. Uncle Bunna just smiled and said “wenyo, hello”, “how are you?”, “where have you been?”

Extending for over a hundred kilometres, Ngargangurie is the longest south facing cliff line in the world, rising to between 60 and a 120 metres in height.

Returning east, we arrived at Miranangu, the Head of the Bight, the most significant sacred ceremonial place where the Mirning practise whale rituals in joint communication and celebration, in song and dance corroboree. Our hearts sunk when met by a barrier across the road; the Elders were locked out, many kilometres away, blocked from performing ceremony and duty. The only signage not even acknowledging the Mirning.

Later that night nothing could block the Yirrerie, the heavens of the Milky Way, the grand cinema in the sky, as the stars winked and laughed with us.

Throughout our journey, the Elders pointed out many bushfoods such as walga, bush tomato, and ngoora, wild grapes.

Uncle Bunna also shared stories about the significance of plants on Mirning country, such as the ngooraum, the totemic home country of the coastal Mirning people, where the ngoora wild grape grows and a beautiful lore of how the nalla tree blossoms as the whales are arriving.

He told of how Jeedara, the ancestral dreamtime white whale, created Mirning country. Whether the ancient seabed of the Nullarbor and limestone coast or the submerged land of the Great Australian Bight, for the Mirning, all of this is within the dreamtime realm of Jeedara, who came from the Yirrerie, the Milky Way. Uncle Bunna explained how the whale continues to be a significant totem and family to the Mirning people. Of course our visit was too early in the season for us to see whales.

Upon our arrival at Djalyingadri, the whale tail of Jeedara imprinted in the land, we were welcomed by dolphins playing in the waves. Then, almost with the skip of a breath, the breakers cleared revealing the presence of the first of the season’s whales: three large southern rights. This felt like an acknowledgement of the Elders at this sacred place, the coming together of family.

High upon the back of Jeedara and joined by two yau, ospreys, Uncle Bunna continued the whale rituals of his ancestors. In smoke, song and dance was a communication celebrating the connectedness of one family together, practices that have persisted since the creation of country in the Dhoogoor, the dreamtime.

It was a tremendous privilege to be invited to take part in this historic journey into Mirning Country with the Elders. Everything is as one; the land, the sea, the animals, the plants and even the heavens. Humans are not somehow separate from the rest of life, something our dominant culture needs to learn swiftly if future generations are to continue in our global ecosystem.

Having dedicated the past 15 years to the conservation of the coastal lands and waters of the Great Australian Bight wilderness, I will be forever grateful for this remarkable experience.

In the words of Uncle Bunna Lawrie “If you listen, learn, understand and observe, then you will receive wisdom and knowledge. For this is the Mirning way”.

What is your role and involvement with wombats?

I'm an affiliate researcher at the University of Adelaide and specialise in wombats with a particular focus on the southern hairy-nosed. I decided to study them because despite decades of research, we don't know a lot about them. A lot of the management decisions on wombats were being made in the absence of rigorous scientific information, so I thought it was about time we went out and got some.

In fact the University of Adelaide owes its very existence to the southern hairy-nosed wombat, which is also the faunal emblem of South Australia. The story goes like this: on the Yorke Peninsula back in the 1850s, there was a shepherd tending his flock, and he came across some unusual rocks outside a wombat burrow. These rocks turned out to be copper ore, and an excavation underneath the warren turned up one of the richest copper finds of all time. It led to the development of the whole area of Moonta, Wallaroo and Kadina, which became the Copper Triangle.

That original mine became known as the Wombat Mine and it is still there. Wombats became loved by miners because they would dig up copper, leading them to important finds. It led to a mining boom, which transformed the state's economy. The hotel in Kadina is still known as the Wombat Hotel and there is a memorial to wombats in the centre of Moonta. The miners protected the wombats; the first Australian animal to ever be protected was the southern hairy-nosed wombat.

Walter Watson Hughes grew wealthy from that copper find and in 1874 he donated £20,000 to establish the University of Adelaide.

The wombat has played a role in the story of South Australia, what role do they play in the environment?

Wombats are known as ecosystem engineers. They are absolutely crucial to the health of the environment and the loss of burrowing animals like the wombat, and to a smaller extent bilbies and bettongs, has really impacted soil health in a lot of places.

Wombats turn over a lot of soil and they break up the hard ground, bringing it to the surface. You can see these white mounds in the middle of patches of brown dirt in the landscape, and that is the wombats bringing up limestone. Over time it's weathered and washes down, fertilising the soil. When they dig and scratch around they make these little pits and furrows that trap nutrients and seeds, which increases germination rates for plants astronomically. If you remove these animals the ecosystem breaks down. Some of these burrows are centuries old, and you can see how they have changed the landscape.

And of course the wombats’ scats help to fertilise the landscape too. They eat grasses if they can get them, as well as saltbush and bluebush. Wombat burrows are also refuges for other animals. It’s bloody hot on the Nullarbor in the middle of summer, and so wombats live underground, but of course a lot of other animals share their burrows: snakes, lizards, insects, echidnas. We've even seen birds and wallabies living in wombat warrens.

Why were these animals on the brink of disappearing from the Nullarbor and how have they made such an impressive return?

In the late 19th and early 20th century rabbits started to spread across the country in plague numbers. It decimated the wombat population. The rabbits would compete with them for food, eating everything, and also push wombats out of their own warrens. At the time and until relatively recently, the only way to control rabbit numbers was to destroy their burrows. And as a consequence of that, wombats became collateral damage. The thinking was: ‘There is a big hole in the ground: bulldoze it, it might have a rabbit in it’... It may also have had a wombat in it, too, but that was the way it went.

Indeed, there used to be quite a sizable population of northern hairy-nosed wombats along the Murray River in the New South Wales Riverina, but back in the 1870s, they actually put a bounty on wombats to destroy their warrens so the rabbits couldn't survive. Within 15 years they wiped out the whole population. I estimate a population of twenty to thirty thousand were wiped out. We exterminated them.

The northern hairy-nosed could have gone the way of the Tasmanian tiger; it’s now one of the most critically endangered animals in the world. When they first started doing research on the northern hairy-nosed wombat back in the 1980s, there were only about 30 individuals remaining. Since then there has been a dedicated, very intense recovery programme and the numbers are up to about 250 now. But that's still very low and they are in just two protected areas, in central and southern Queensland.

Now the rabbits are under effective control, firstly with myxomatosis and more recently with calicivirus. Since the 1960s, southern hairy-nosed wombat numbers have been recovering and it really has started to bounce back in the last 20 or so years.

Are you seeing an improvement in the health of the Nullarbor as a result?

Absolutely. One of the places where we've seen the biggest change are places in the south where they've converted some old sheep grazing properties to wildlife conservation areas. And the whole ecosystem has been improving. It's much more healthy, with more animals and different species around. And the soil health is greatly improved, there is better vegetation growth as well.

Can you easily spot signs of wombats when driving across the Nullarbor?

You'll certainly see their warrens everywhere; it's hard not to see them. Once you get just west of Ceduna, all the way across the Nullarbor you'll see warrens everywhere. Bare-nosed or common wombats tend to live in single burrows, which is nothing on a scale of the southern hairy-nosed. The largest I have seen is roughly the size of the Melbourne Cricket Ground, with up to 70 entrances and there might be 20 to 30 animals living inside it.

Most people have this incorrect notion about the Nullarbor that it's just flat, but it's a fascinating landscape. It has micro-topography, which has a huge impact on where animals can and can't live. It’s an endlessly fascinating and iconic place.

Is the future looking bright for the southern hairy-nosed wombat?

It’s looking pretty good, but there is the impact of climate change. The southern hairy-nosed wombat really needs two seasons of reasonable conditions for the young to survive to maturity. In the Nullarbor droughts are becoming more frequent, which means there could be more periods where the young are not going to survive to maturity.

They'll survive because they're hardy animals, but the numbers could decline substantially in some areas. The scats can tell us a lot. I collect scats—I have freezers full of wombat poo—it’s a hobby of mine. We can look at the epithelial cells on the outside of the scats, which tells us about the genetics of the animal. We can look at the genetics of the plants they eat, what their diet is like. We want to look at the genetics between different populations to determine how they are moving across the landscape.

From all this we can determine what measures we may need to take to protect the species. We don't want them to go the way of the northern hairy-nosed wombat and get down to 30 animals before we take action. If we can get advanced ideas of what's going on, we can actually start thinking about the areas we need to protect to ensure a future for this icon of the Nullarbor.

Just below the surface of the Nullarbor lies a secret world frozen in time with the skeletal remains of the marsupial lions, thylacines and devils that once thrived here. A continued source of knowledge for the Mirning for more than 65,000 years, the caves are a window into Earth’s deep past and a glimpse into the future.

Words: Dan Down

Jon Woodhead, a Professor of Earth Sciences at the University of Melbourne, has been studying this underworld for some 15 years. “We only know about 700 or so caves, but it is estimated that there may be many thousands, which would make this the most extensive cave network in the world,” says Prof Woodhead. “But their global scientific significance is really because of their age—most of them were formed between three and eight million years ago. And the fact that they are so remarkably well preserved is unusual. There is nowhere else on the planet with such an abundance of well-preserved ancient caves.”

The Nullarbor’s vast limestone karst formed on an ancient sea floor between 15 and 25 million years ago. This seabed was then uplifted 15 million years ago to form the Nullarbor Plain we see today. The caves stopped forming about two and a half million years ago as a wet continent dried out, leaving them frozen in time along with the remains of extinct megafauna.

Down here, the fossils of thylacine, tree kangaroos, and Thylacoleo carnifex, the marsupial lion, are a goldmine for scientists unravelling Australia’s iconic natural history. “Some passages open out into these beautiful caverns. In many cases they’re full of stalagmites and flowstones,” says Prof Woodhead. “But unlike modern caves they're not wet; they're dry and dusty because the formations here are no longer active and can be millions of years old. So it's like entering a lost world.”

How have we been able to grasp these unfathomable timeframes? “We date the caves by looking at the stalagmites and the flowstones, which contain minute amounts of uranium. This slowly decays over time to the element lead,” explains Prof Woodhead. “We use very sensitive instruments to measure tiny amounts of uranium and lead in the calcite, which allows us to determine the age. The oldest materials we've found are around 10 million years old, which likely represent the first stages of the caves’ development.”

Prof Woodhead is trying to answer how the caves formed and how the continent evolved. “Once we have the ages, we can then look at materials that are either trapped within the samples or the composition of the samples themselves to reveal what the climate was like, or reconstruct the vegetation around the cave all those millions of years ago. We do that by extracting fossilised pollen; over time pollen has been blown into the caves and become trapped in stalagmites as they're growing.”

"The fact that they are so remarkably well preserved is unusual. There is nowhere else on the planet with such an abundance of well-preserved ancient caves."

Prof Jon Woodhead, University of Melbourne

Just as scientists study ice cores taken from the Antarctic to reveal past climates, so the Nullarbor’s caves are proving a vital record of the Earth’s pulse. “Most of these formations were formed in a period called the Pliocene, which was about two-and-a-half to five million years ago. It's a really important time in Earth's history because it's a very good analogue for future global warming,” says Prof Woodhead. “We think temperatures in the Pliocene were about three degrees hotter than today. So the Pliocene was kind of what the future world will look like, possibly as soon as the end of this century.”

And herein lies a mystery, because the Australian continent is currently drying out. “All the predictions are that southern Australia, in particular, is going to get drier and drier. But when you look at the Pliocene, it is actually very wet, so there could be a tipping point where things get wet again.” Indeed, the remains of tree kangaroos in the Nullarbor’s caves from hundreds of thousands of years ago point to a landscape once covered in lush forest.

“It just goes to show that if we just look at the land through the filter of today, then we are not really seeing the whole picture,” says Dr Liz Reed. A vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of Adelaide, she is studying the Nullarbor’s wealth of ancient animal remains, exploring the fossil record from some 20,000 years ago up to today, to see how biodiversity has responded to environmental change.

Prof Woodhead’s work has been critical in allowing her to understand the ancient climate context of sites where fossils are found, and the closer you get to today, the more sobering it becomes. “If I walk out into the Australian bush, I see a mere shadow of what the original biodiversity was like,” she says. “It is a bitter pill to swallow. We have caused devastation on a number of fronts in the short time since the European settlement, with land-use change, the introduction of domestic livestock and feral pests.

“You can drop into a cave, look at a pile of bones and see bandicoots. The Nullarbor barred bandicoot is gone; stick-nest rats: gone; bilbies: gone; mulgaras: gone. And they were so abundant on the Nullarbor; the owls were hunting these animals, bringing thousands back to the caves, coughing up pellets and leaving the bones. But now they are gone. You get quite emotional when you go into a cave and realise that what you're looking at is extinction.

“And these are recent losses, which is really sad. The Nullarbor has such a strong cultural history. I have had the opportunity to understand that perspective, that amazing relationship with Country. The exchange of information certainly helps me understand what I am looking at in the caves as I try to reconstruct the biodiversity that First Nations people lived with here for tens of thousands of years.”

"You get quite emotional when you go into a cave and realise that what you're looking at is extinction."

Dr Liz Reed, Universtiy of Adelaide

The fossil record reveals the distribution of species in response to changing climates, providing a forecast of how Australia’s precious remaining fauna could respond to rising temperatures again. “We know that devils and thylacines went extinct on the mainland about 3,200 years ago; we know they were once widespread from fossils found in places like the Nullarbor,” says Dr Reed. “With the climate data and pollen from the formations we can look at what drivers led up to those mainland extinctions.

"The thylacine specimens we have from the Nullarbor are small compared to those found on the East and West coasts and Tasmania, indicating an adverse environmental change. We are now trying to find relatively young cave formations so that Prof Woodhead can decipher more about the climate around the time of the thylacine’s disappearance."

The fossil record can also be crucial when we look at rewilding or revegetating areas. "It helps us understand the original faunas and how they filled functions in the ecosystem,” says Dr Reed. “Tassie devils were recently reintroduced back to sites in New South Wales, and so a native carnivore is now fulfilling its role once again. We know they were there from the fossil record.”

The work is gathering pace. Coupled with the careful timestamping of Prof Woodhead, a complete picture is emerging of the Australian continent, its flora, fauna and climate. The underground wonderland could help us plot a path for wildlife as we enter a Pliocene-like world of our own making.

But these caves aren’t just special because of what we can learn from them, they are wonderful in their own right—for their cultural significance, the unique lifeforms they harbour, and their natural rock formations millions of years in the making. “I like to call caves the rainforests of the underground,” says Dr Reed. “They are just as biodiverse, just as delicate, just as important from a conservation perspective, they are intimately tied with groundwater. I think they really are the most fragile terrestrial ecosystems on Earth. The Nullarbor is unique. It is an important place to conserve not only for Australia, but for the world.”

Throughout the next few years our campaign called for the protection of the Nullarbor wilderness and negotiations around possible outer boundaries of a Wilderness Protection Area were conducted together with the Mirning and key stakeholders, primarily the mining industry. Our aim was to protect as much of the Nullarbor cave system as possible and the iconic Bunda Cliffs (Ngargangurie), all the way to the end of South Australia’s legal jurisdiction at the SA/WA border.

Finally, in 2013 about 900,000 hectares of the Nullarbor Plain, including the cliffs and an extensive cave network, was proclaimed a Wilderness Protection Area. For context, this is about the same size as the famous Yellowstone National Park in the USA.

Connected to the Great Australian Bight Marine Park, this creates a land and sea conservation estate of grand scale and international significance. Imagine if we could achieve recognition for the whole of this outstanding ecosystem, beyond jurisdictional borders.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.