Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to the tenth issue of our Journal. Each edition we share stories of nature and people. Photographers, artists, citizens and scientists share insights into the beauty of wildlife, wild places and what is being done to protect them. Plus a look back at the Wilderness Society's rich history in pictures. Image above: View of Hill End from Bald Hill, 2021. Etching by Bruno Cowen (detail).

Kristen Lang is a poet. Her most recent book, Earth Dwellers, celebrates many kinds of landscapes—deserts to mountains, rivers to oceans. A number of the poems are distinctively Tasmanian, a fact explained by her residence in the north-west of the island. Yet Kristen’s focus is global as well as local. Her gaze returns frequently to the ways the more-than-human world is and could be regarded within our modern societies. The poet David Brooks refers to the collection’s “deep wisdom, an engrossing meditation upon our profound interconnectedness”. It’s this interconnection, as it impacts on our spirit, our survival, our safety, and on our responsiveness to the world around us, that Kristen explores in her writing. The damage being inflicted on the environments of which we are a part is an obvious concern. What can poetry do, she asks, against global habitat loss or global warming? Here, in her words and with readings from Earth Dwellers, she posits that the answer lies with cultural change.

We have a tendency to see and care for humans beyond all else. It makes sense, you might think, though from anthropocentrism we’ve moved now to the Anthropocene, exposing the insanity that has been fed by the extent of our blindness.

In truth, we’re selectively anthropocentric, favouring some kinds of humans and human behaviours before others. Often the conflicts among ourselves hold us all the more distant from the state of our home.

We know Earth contains an enormous array of life, more than we’ve identified, far more than we understand. We know there are trillions of ecological interactions going on all around the world every day, every hour, every second. Most of us believe what is said about everything being connected: one Earth, nothing without a consequence.

Yet for most of the time, in supermarkets and offices, on the share market, on the net and in the movies, in the houses of parliament, on the roads and in the streets, it’s as if modern humans are the only thing of importance anywhere that matters, particularly in as much as we are able to serve this god-like, narrowly conceived economy.

Where ARE the trillions of other creatures we share the planet with? What are they doing? There’s a whisper they’re not doing so well. We’re losing diversity. Habitats are disappearing. Or are so polluted as to be deadly. The climate is changing. Storms, fires…

Do we change our behaviours? We know there are other ways of relating to the world we’re part of. More responsible ways. More just ways. More inclusive ways. And a growing number of us know it matters.

This is the mood in which I began writing the poems in Earth Dwellers. Between beginning writing and publication, the issues contributing to this mood have only become more intense. The book is a celebration, full of places I love and life I am glad to be close to. It’s also a plea.

I moved to Tasmania as a two-year-old, my parents being tree-changers out of Melbourne. We moved to a house in the woods without power, without neighbours, and where the only night lights were the stars.

When the bush I’d been growing up in was being clear-felled, I pretended the sounds were those of a great citadel being built, a magical place full of light and hope—anything, I thought, would be better than believing the forest was being taken down. Trees I’d seen eagles in. Owls and thornbills. Sugar gliders. Ring tails. Soil I’d seen erupting with fungi and slime moulds. This was orb spider country. Stringybark and pademelon country. Cloud and sun and wind caught and thrown by the leaf tips of its forests.

I was right, of course. Cities full of light were being built. They were and are being built by the remarkable human societies we’re all familiar with, founded on science and commerce, on ingenuity, communication, and on, as well, I think, this immensely sad idea about a civilised separateness, as if the imagined divide between modern humans and everything else were complete and unquestionable, as if that divide might justify all kinds of horrendous behaviours.

This separateness allows “everything else” to be boxed up as one of two things: either irrelevant to or a resource for the machine of infinite growth. One or the other. Neither marries well with humility, with care, or with responsibility in relation to the ecosphere. And I wonder how much of a crisis point we have to meet before this humility, care and responsibility might become part of our societal wisdom.

Where we are, this island of life in the universe, is incredible. We’re part of it. And all of us lose if we continue to exclude the biome from our thinking. So how do we begin to be more inclusive? As a writer, I think about the words and stories I’m able to share. Descriptions of ourselves entangled with where we are:

as we talk

heat scraps from our lungs

become the sky

I want to offer stories that trace our own roots into the billions-of-years’ history of the planet. I want to feel the presence of ecosystems, the ongoing exchanges and yes, as well, the impacts we might wish we were not having. I want to know our recent, short-lived selves as creatures amid all these other lives, how ultimately we’re all of the same stuff, on the same, single planet—you, me, the tree, the rock, the dinosaurs…

each atom –

all the years of travel

bolide liverwort crane fly

before becoming you

The natural world isn’t a thing that can curl up on your lap and affectionately lick your hand if you are kind to it. Earth Dwellers isn’t intended to be a book about living hand in hand with nature. You can’t live hand in hand with something you’ve never in fact been divided from. There isn’t a relationship, in this sense, it’s not a friendship between separable entities. Rather, there’s an interconnectedness, an always-already embeddedness that deserves, above anything else, regard. When we say “I live here”, I’d love that sense of “here” to be billions of years old and dense with physical, biological, ecological exchanges, ongoing co-existences, sharings of atoms.

Should we be hopeful about the future? Today, ecological restoration is on the rise. At once, pain through loss (of forests, of marine environments, entire species) is also on the rise. A desire for stronger environment laws exists among many. Resistance exists alongside it. An appreciation of the connectedness to land suggested by Indigenous concepts of country and belonging is increasing.

Perhaps it's useful to remind ourselves: we are all of this Earth. It's a simple truth. Yet to me it feels hopeful. We're not going to care for something we don’t belong to. And the sooner we perceive ourselves as family members not even of a global human population but of the global phenomenon of life, the better.

Perhaps our first ambition can be to allow ourselves to be changed by the places we’re in, to make room for them, to allow them to re-write us instead of the other way around. And I mean this for city dwellers as much as for anyone else. City air is the Earth’s air. City water is the Earth’s water. Under the concrete there is soil. And everywhere, and in all of our behaviours, there is the chance to recognise we are part of something larger than ourselves.

Earth Dwellers, by Kristen Lang, is available at bookshops and via Giramondo Publishing. Kristen’s other books, SkinNotes (2017), The Weight of Light (2017) and Let me show you a ripple (poems and photographs, 2008), are available at her website.

Kristen Lang will be hosting writing workshops during the Wilderness Society's Nature Book Week, commencing 6 September.

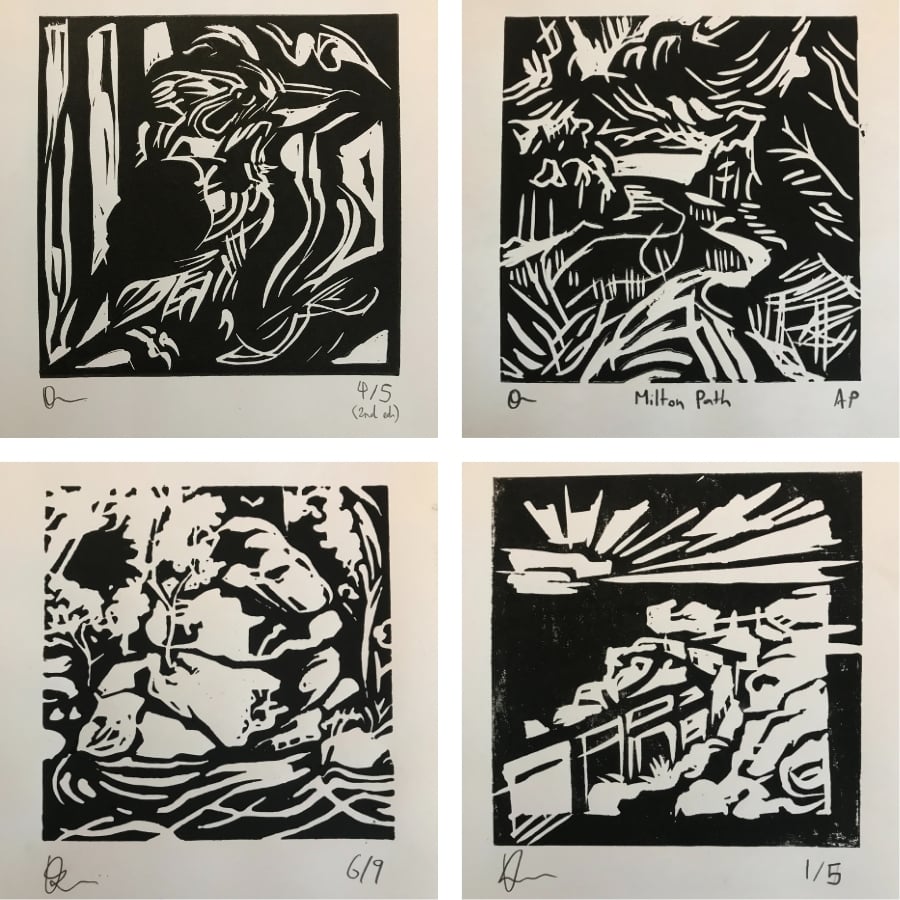

Words and artworks (including etching top) by Bruno Cowen, 21, artist and musician.

These pictures are all lino prints or pen drawings that I’ve done over the past few years. Each picture has a commemorative purpose of some sort, and until seeing them compiled like this I hadn’t realised the extent that they were all of natural imagery like the bush. Whether the picture was serving as a playlist cover or a present for a friend, they all seek to capture some moment of quietness and calm appreciation, a mood which seems to be captured mainly by close engagement with natural forms. Most of the pictures are of spots in the bush near Milton in country NSW, a place I associate with rest and contentment. Hopefully something of this is present in the pictures.

Film Jennene Riggs; words Dan Down

Actor and naturalist George Shevtsov discusses the power of volunteering and filming for the new docuseries Rewilding The West. It's a journey through remote islands and wilderness charting efforts to save the world’s rarest animals.

An ardent bird-watcher and orchid obsessive, when he’s not treading the boards George assumes the role of naturalist. “But I got to a point identifying orchids and birds with field guides where I hit a dead end,” he says. “I thought, ‘maybe my partner Linda and I could learn much more by joining groups’.”

They started with orchid and wildflower societies and from there discovered the world of volunteering, a journey that has taken them to far-flung corners of the country. “I’ve been able to trap, measure and handle honey possums and all sorts of incredible blind snakes. I’ve studied North West Shelf flatback turtles on Thevenard Island off the coast from Onslow and monitored Western ground parrots in Cape Arid National Park, east of Esperance,” he says. “I think I get more pleasure doing volunteer work than I do from making movies or being on stage!”

It was while monitoring populations of the extremely rare Western ground parrot that George met filmmaker Jennene Riggs, who was documenting that important work. It was the perfect collaboration; George’s two worlds of film and volunteering are now merging in docuseries Rewilding The West.

The series explores the ground-breaking research taking place in remote parts of Western Australia to preserve some of the rarest animals on the planet. Animals like the Ngilkat (Noongar) or Gilbert’s potoroo, the world’s rarest marsupial and Australia’s rarest mammal. With George as host, it’s also about the power of volunteering to keep our most threatened species alive. Filming has taken him to some of the most isolated corners of Australia, to islands being used as predator-free arks to foster insurance populations of animals on the brink of extinction. “Only a lucky few volunteers and scientists get to set foot on some of these islands, so it was a privilege to be there and be involved,” says George.

Becoming a conservation volunteer, having the opportunity to meet some of our most elusive animals, has been transformational. “It was a blossoming,” he says. “My heart opened up even more to nature because you don't see these creatures when you go bush, there’s just so few of them left. But when you volunteer and get hands on, suddenly... there they are! You trap them, you measure them and then you release them, and you actually have a real physical connection with something that you can normally only read about.”

But giving your time to help out isn’t all about getting close to the world’s rarest and wonderful, and George isn’t one to shirk the hard jobs; he’s just as happy setting up dunnies for tourists. Need a loo stop on the Nyangumarta Highway in the Pilbara and you’ll find some of his recent handiwork: roadside toilets he helped build with Indigenous rangers and a volunteering group.

Indeed, it was a local group, the Gilbert’s Potoroo Action Group, that helped facilitate Jennene and George get onto Middle Island in the Recherche Archipelago to record the critical work being done there. George helped with the trial release of Gilbert’s potoroos being carried out by Dr Tony Friend from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA). “One or two volunteers come along because that's basically all they need. So it's the lucky few who get to go. And then you've got to be fit to be traipsing: you're going on hikes every day to do the work,” says George.

The Gilbert’s potoroo was thought extinct until it was rediscovered in 1994 at Two Peoples Bay. Facing imminent extinction from feral predators and habitat destruction on the mainland, an insurance population was established on Bald Island offshore of Two Peoples Bay. “The first translocation of Gilbert’s potoroo was from the mainland in 2005,” says filmmaker Jennene Riggs. “They put some onto Bald Island and that was successful. And then a bushfire wiped out all but a couple of the Gilbert’s potoroos at Two Peoples Bay. So the island ark saved the species.”

“There are so few of them,” says George. “There was just the joy and the pleasure of connecting with these animals. They used to flourish but now it’s a secret life. Volunteering gives you access to that secret world.”

Rewilding The West follows the potoroos’ journey from Bald Island to their new home on Middle Island. “They needed another island home because one lightning strike could start a bushfire and wipe them out. It’s so frightening,” says George.

It was on Bald Island that the team met another resident: the Jimuluk (Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar), or noisy scrub-bird. With the guidance of Sarah Comer, regional ecologist for the DBCA, George helped catch some of the birds for relocation. “Ah, the amazing noisy scrub-bird,” recalls George. “They have the decibel range of a jet plane.”

The series takes you island hopping. As well as Bald and Middle Islands, there’s the work of scientists introducing populations of rare rufous hare- (Mala) and banded-hare wallabies on Dirk Hartog; there’s the capture of insanely cute dibblers (common name adopted from the Wagyl Kaip and Southern Noongar), one of the smallest carnivorous marsupials, on Escape Island for a successful breeding program at Perth Zoo. And there is more story to tell, the filming now taking George and Jennene to some of the mainland wilderness reserves that feed rare species for these island arks.

Working as a volunteer so close to the edge of species extinction can be as sobering as it is joyful. “When you get to go out to the bush and see and touch these animals, it is such a different experience, it touches you much more deeply,” says George. “The animals in this country are mythical. We want to show that these creatures exist and they are palpable and living and sentient. And they are so important to us spiritually; we are not living in isolation. We save these creatures not only for their own sake, but because they’re part of us.

“Maybe if more of us thought of a tree, a hill or a rock as not just part of a landscape, but as something living and present and alive and meaningful, then maybe we wouldn't be so ready to destroy it.

“That's why Samuel Beckett still speaks to us so strongly in the face of no hope; we still stay and we still wait. We still hope.

“These islands are a source of hope.”

Set to be released in the first half of next year, find out more about Rewilding The West and lend your support.

Marina DeBris finds the ugly beauty in the things we discard, rejected by the ocean on our beaches. With her signature irreverence her works of art and fashion, carefully crafted from collected rubbish, are intended to provoke and spark dialogue about our throwaway society.

On the rubbish trail with artist and ‘trashion’ creator Marina DeBris. Photographs by Elise Lockwood

"I work with the rubbish I find on beaches purely out of passion, to address environmental issues. No other reason. Although it has been fulfilling to be an artist.

"I’ve been doing this for just over 10 years. I like to keep people guessing and questioning things. Earlier this year I had a show at the National Maritime Museum, Beach Couture, which featured my ‘trashion’, my fashion pieces, but there was also my installation called the Inconvenience Store, a mock shop with items of repackaged rubbish I’ve found. It features ‘plastic chucklery’ and ‘Chips ahoy’ [empty crisp bag], and ‘Straws—They really suck!’. It's kind of part of my nature to be a bit cheeky.

"I did a similar piece for Sculpture by the Sea in Sydney in 2015. I built a giant aquarium and filled it with dangling pieces of rubbish that look like sea life. There was a mock sign with scientific names for every object that was in there, as if it was a fish or some other form of sea life. For each piece of rubbish I explained its habitat, where it's found, what it did. And it was really tongue in cheek; I like to open dialogues.

"With my trashion and the wearables I make, I just sort of muddle through and sometimes I get lucky and a piece works, sometimes it doesn't. I'm just doing it by gum and spit.

"The pseudonym just happened. Ninety-nine percent of what I do is just where my gut is taking me, and I don't really think about it that much or analyse it. I just felt like I didn't really want to use my real name because it's quite meaningless. And I like just having fun—it's been really interesting having an alternate persona.

"I am American born and bred, and went to the Rhode Island School of Design before I moved to New York City, which I consider my spiritual home. I moved to London and I was excited by the craftsmanship going on in the fashion scene there; I just loved it. And then I lived in Los Angeles, Venice Beach, which is actually where I got started in this whole journey of turning rubbish from the sea into fashion and art installations. I was running along the beach every day and I just noticed there was rubbish washing up. I was scratching my head thinking, ‘This is bizarre'. I started picking up the rubbish, not knowing what to do with it. If it had a label on it I'd take it back to where it had come from and try and explain the problem. I started getting involved with a few local groups there and then it just came in a flurry. In 2009, I started creating stuff. I didn't think about it, really. It was just my method of trying to do something.

"I also live in Sydney, where I have a strong connection to the ocean. I find it shocking to find rubbish here, because the beaches and the ocean here are so sacred. It's scary because I can guarantee that all the rubbish I find on Sydney’s beaches is local. It's not coming from other islands, it’s not coming from other countries.

"People mistakenly think that I just work in plastic. It's not just plastic; it's all of our waste. I find just as many aluminium can bits washing up as plastic fishing gear. I find clothing, balloons, heels of shoes, pegs and string virtually every day.

"With my work I'm trying to be as confronting as possible. In fact, in my daily ritual, I can be quite confronting. I pick up rubbish every single day on two beaches, and on days when it's really bad I will lay out my haul on a footpath. Sometimes I'll make it into an S.O.S or an unhappy face. The other day I put it in a little toy dump truck that I’d found, because my theory is that if I just pick it up, put it in the bin, that's it. Out of sight. Out of mind. Nobody has to face it. When I put it on the footpath people have to look at it and a lot of people get really pissed off at me. People have yelled at me.

"I always put it in a place where it's not going to go back in the ocean. That's paramount; I don't put it out when it's raining heavily or really windy. So it's not just haphazard, and I try to put a symbol on it, so it's not just a pile rubbish. But sometimes, it is just a pile of rubbish.

"We're the ones creating it; we're the only species making this mess. So why shouldn't we have to deal with it? All the marine animals have to deal with it, they have no choice and they're dying or getting injured from our waste. If somebody walks by one of my rubbish piles on a path and asks, ‘Why are you putting this here? It's just in the way!’ I reply, ‘Yeah, that's exactly right.’

"I know it's not the answer. However, I take so much of it home and have to sort through it. It's very time consuming, but I figure that’s doing something rather than nothing. We all have to wear clothes, we all have to buy certain things to survive, but it's about being conscious of everything that we buy and where it’s going to end up.

"Sometimes I find really cool things. I like the way the ocean wears down plastic. Plastic bottles especially can look very organic and kind of almost beautiful in a way. But in the end, it's ugly, it's very ugly, and I would rather it not be in existence. However, I do appreciate it and I suppose that's the only way I can do what I do, because I have to know visually if something looks super interesting and I can use it.

"In the end it would be ideal if I ended up going out of business and wasn’t able to find any waste on beaches. That is the goal."

Marina's work is currently on display at the Wynyard MetCentre, store 652, in Sydney, and at Greenwood Plaza, shop M68, in North Sydney. Upcoming exhibitions include Transformation: Art in the Recycle, Lions Gate Lodge, Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 1-15 August; and Beach Couture: A Haute Mess, Cairns Museum, 3 December-26 February.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.