Wilderness Journal #030

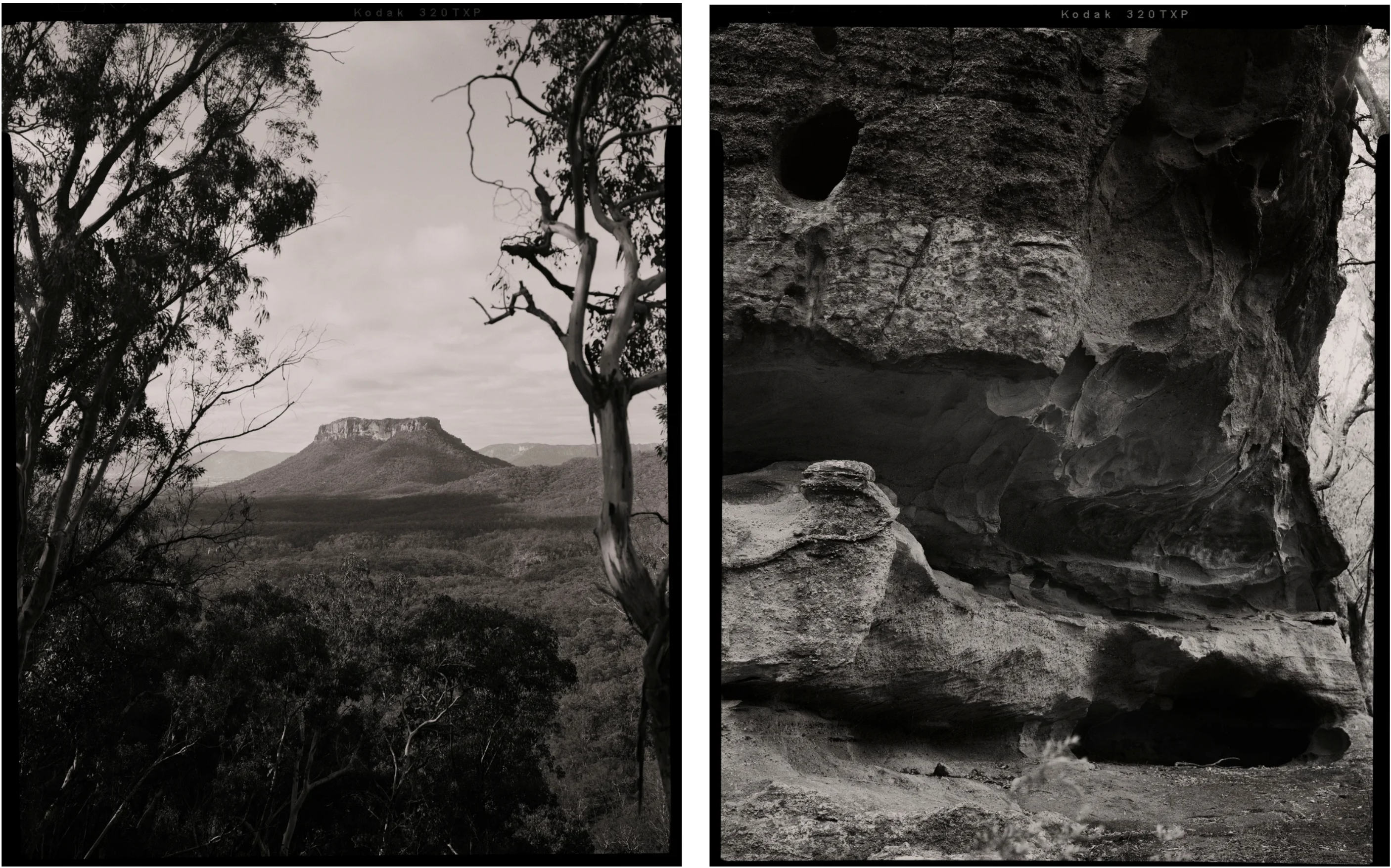

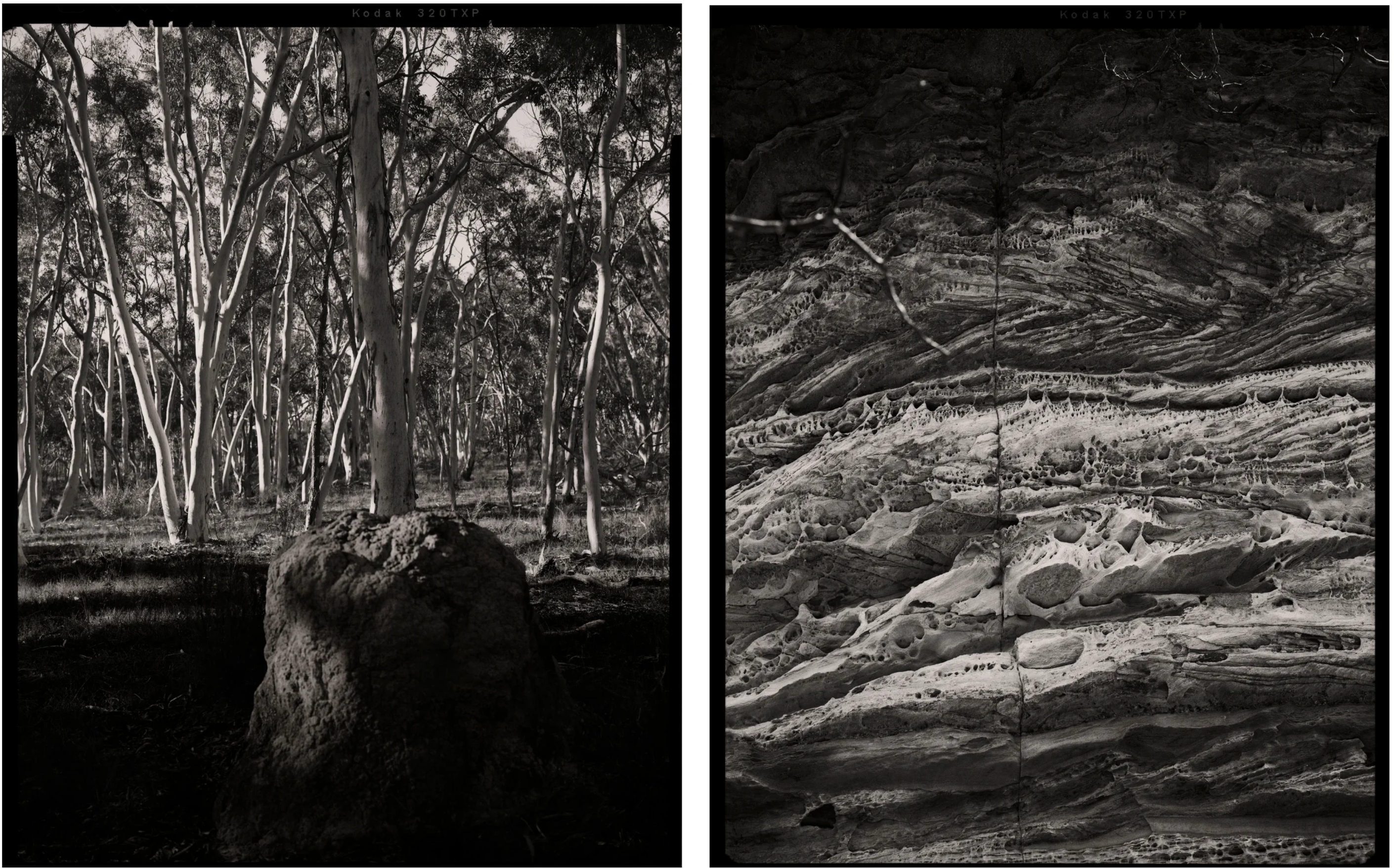

This edition focuses on the people, landscapes and wildlife of the Blue Mountains, NSW, and Wollemi National Park in particular. Wollemi forms the largest and most-intact part of the Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area, listed for its exceptional diversity of eucalypts and other flora like banksias, waratahs, tea-trees, she-oaks and wattles. Meet the people that want to protect this unique landscape and its rare and wonderful animals from the devastation of fossil fuel mining.

Above: Wollemi National Park, Darkinjung Country (left); Ganguddy / Dunns Swamp, Wiradjuri Country (centre, right). Photographs by Ingvar Kenne.

Words by Victoria Jack, photography by Ingvar Kenne.

The people living in and around the town of Rylstone, west of the Blue Mountains on the doorstep of Wollemi National Park, have been through a lot of late. They emerged from drought and the devastating 2019-20 bushfires only to face a new threat: the possibility of a brand new coalfield amid fertile farmland and World Heritage-Value forests. Despite the fact many are still recovering from recent disasters, they met this new challenge with a determination not to give in. NSW Campaigns Manager Victoria Jack joined photographer Ingvar Kenne to meet the people and share their story: one of steadfast resolve to protect the nature and First Nations cultural heritage of a remarkable landscape they call home.

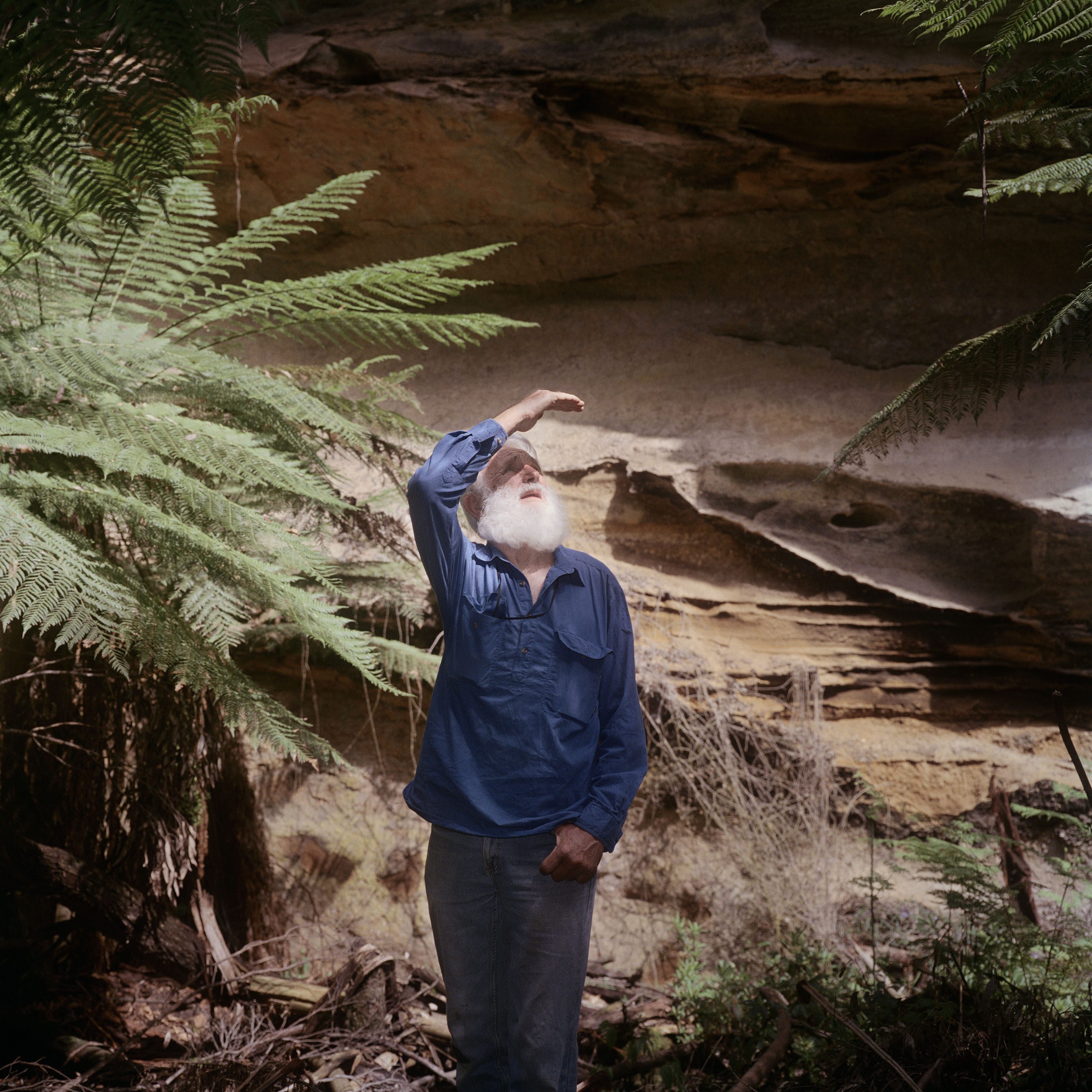

Peter Swain is from the Dabee clan of the Wiradjuri nation, where his ancestors have lived for thousands and thousands of years. This is the Country where his great-great-great grandmother, Peggy Lambert—who escaped the 1824 Capertee Valley massacre as a child—later died by hunger strike on the banks of the Cudgegong River, because she’d “had enough” and “wanted to go back to her old people”. Peter knows this Country deeply, and he’s worried about its future. “Unprecedented fires followed the unprecedented drought,” he says of the disasters that struck this region in recent years. “Next it will be unprecedented something else.”

Before long we come across a cave featuring a rock art painting made from red ochre. There are scores of publicly listed First Nations cultural sites in these parts—and no doubt many more yet to be documented. Traditional Custodians have been working to connect with landowners so they can visit parts of their Country that were previously locked off, preventing access to cultural heritage sites for hundreds of years. These sites are connected through a story of who was here and what they did, Peter tells me. That’s why it’s critical to protect them all—because to damage even one means another piece of a Songline is broken.

Last year a spotlight was shone on the destruction of sacred sites by mining companies in Australia when Rio Tinto exploded the 46,000-year-old Juukan Gorge rock shelter in the Pilbara. While it’s a particularly egregious example, it’s far from unique. Mining has long been a relentless threat to First Nations cultural heritage—including on Wiradjuri Country, where landscapes have been forever altered and cultural sites lost. To protect this region from further destruction of sacred sites, and to protect Country from the increasing impacts of climate change, Peter says it’s time for a drastic rethink of what we allow to happen to the land and waters that sustain us. “We’ve been taking the magic out of the land for far too long,” he says. “Now we need to put some of the magic back.”

Despite a major global push to accelerate the end of coal, the NSW government has earmarked eight new areas for coal exploration under its Strategic Release Framework. These include parts of Wiradjuri Country near Rylstone, on the border of Wollemi National Park. Ultimately, this plan could see a new coalfield built on the edge of the largest and most intact part of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

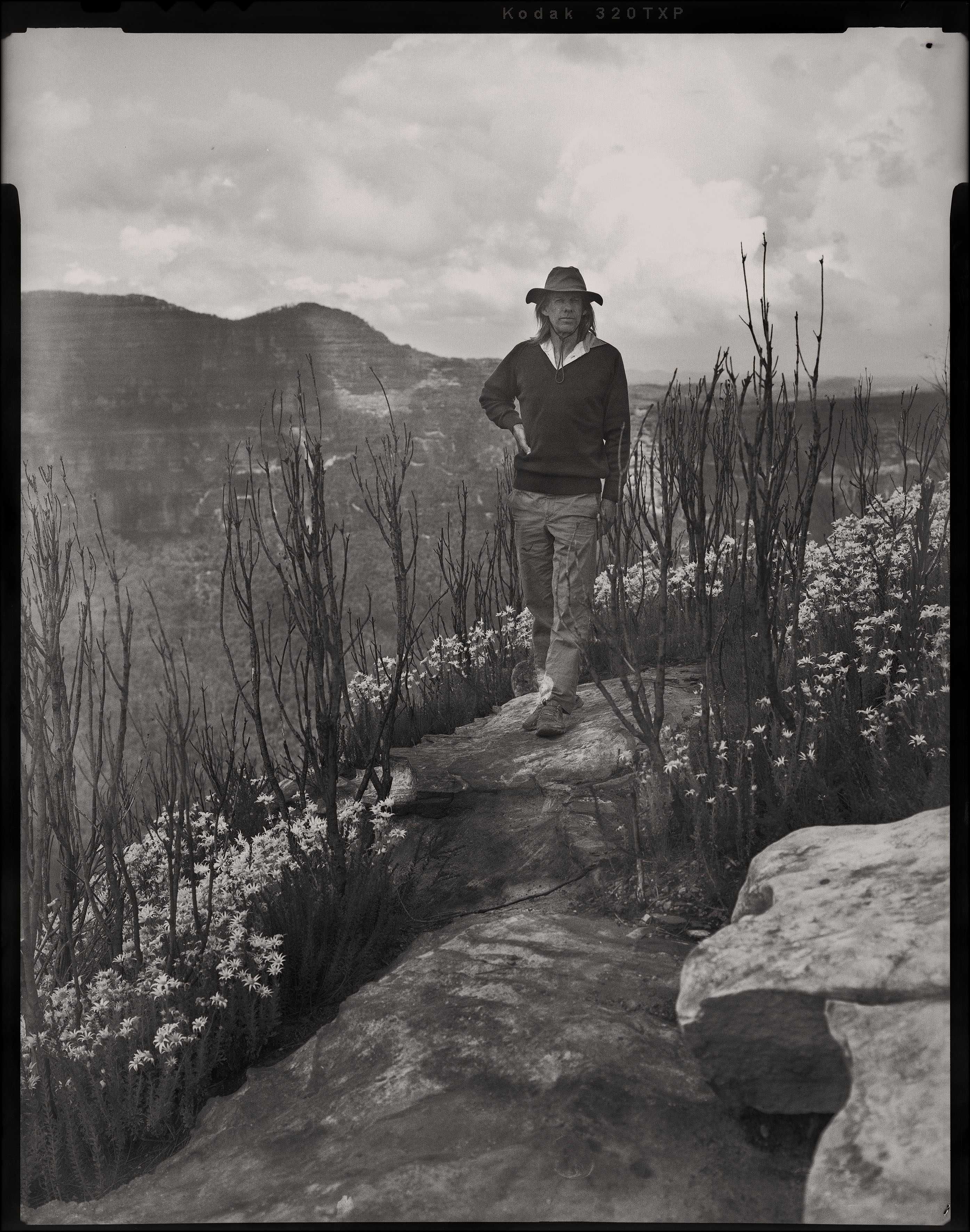

Wollemi National Park is home to many unique species, including the world’s last wild Wollemi Pines that date back to the time of the dinosaurs. There are less than 100 adult Wollemi Pines remaining, and they’re so precious that the National Parks and Wildlife Service keeps their location secret. Threatened and vulnerable creatures live here, like koalas, the glossy-black cockatoo and the spotted-tailed quoll. There are 120 known First Nations cultural heritage sites in Wollemi, on lands and waters significant to the Wiradjuri, Dharug, Wanaruah and Darkinjung peoples. “If mining is allowed adjacent to the national park, people who visit will be accessing these places from what could become moonscapes, like in the Hunter Valley,” says geologist Chris Pavich, who works to protect the Wollemi Pines and was a ranger in Wollemi for more than 20 years. Chris is worried about a range of impacts, including the loss of feeding habitat in areas neighbouring the national park, which may be frequented by animals like the endangered brush-tailed rock wallaby.

Not only would a coal mine threaten Wollemi and its World Heritage status, it would devastate the neighbouring intact landscapes where coal exploration is proposed. This includes two state forests that have been nominated for inclusion in the National Heritage List as a step towards inscribing them in the World Heritage Area. Another special place not far from Rylstone is the Ferntree Gully Reserve, which is home to 25 threatened species of birds, plants and animals. Mal Stokes, a naturalist, and Mike Pridmore, an environmentalist, are two of a group of volunteers who have spent thousands of hours maintaining the reserve. They are both worried about the impact coal mining would have on places like this if the NSW government allows it to go ahead. “When the government thinks of natural resources, they only think of coal,” Mal says. “But nature is priceless.”

Rylstone Region Coal Free Community group is leading the fight against the mindless expansion of the fossil fuel industry in their backyard. Rylstone thrives off agriculture and tourism—and that’s how it should stay, says group president Cheryl Nielsen. The nearest active coal mines are Wilpinjong, which is an hour’s drive north, and Airly Mine, about 40 minutes’ drive south. Cheryl runs a successful farmstay on her property, which is not far from the popular Ganguddy-Dunns Swamp picnic area on the headwaters of the Cudgegong River. She’s one of many tourism operators in Rylstone and surrounds, serving visitors who come from all over the world. If a mine is built on the border of Wollemi National Park, there’s no doubt tourists will stop coming, Cheryl says. “All this destruction when coal will only last another decade or two. How can you justify it?”

Part of what makes locals in this area so passionate about fighting the prospect of a coal mine is that they’ve seen the extreme impacts of climate change up close. Two years ago their lives were turned upside down when the biggest forest fire in Australia’s history arrived on their doorstep, during the Black Summer 2019-20 bushfire season. The fire started from a single ignition point on Gospers Mountain, in a densely forested part of Wollemi National Park, before crossing over to threaten properties in surrounding areas. It joined with four other large blazes and burned for 79 days. All up, the fires burned through around 81 percent of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Area.

After years of crippling drought, the scene was set for the fires to take hold with brutal efficiency. “It was so dry, it was like napalm going off all around you as soon as a spark hit the ground,” Michael Suttor recalls. He’s been the captain of Nullo Mountain Bushfire Brigade for 30 years, but in all that time he’d never before seen a blaze so fierce and enduring.

We hop in the Land Cruiser and take a drive to look at the impact of the bushfires near Michael’s sprawling property in ‘Ganguddy-Kelgoola’, one of the areas earmarked for coal exploration on the border of Wollemi National Park. While charcoal trunks punctuate the landscape, so too do green shoots. Michael says the biggest problem is that so many large old trees were killed—and any new growth will take a long time to reach that level of maturity. He’s confident the bush will eventually recover, but reckons the same can’t be said for the impacts of coal mining. “The country will regenerate… but a coal mine will destroy everything. You can’t tell me they can put it back the way it was.”

Shireen Baguley, the vice-president of Rylstone Region Coal Free Community, is still replacing fences on her property that were destroyed by bushfire. Hearing that her community could become the site of a new coalfield while she was still recovering from the trauma of the fires was “the cruellest blow”, she says. “We’ve been left in no doubt we’re on the frontline of climate change… and the government now wants to put a massive new coal mine on our doorstep?” Shireen says her community is facing a similar battle to residents in nearby Bylong Valley, who fought for a decade against a proposed coal project. “We realise that what happened in Bylong could happen here: the displacement of the community, the uncertainty, the loss of investment, and the real threat that a mine could be built here in this beautiful and special place.”

Despite the emotional toll involved, the Rylstone Region Coal Free Community group is committed to fighting against a new coal mine in their community for as long as it takes. It’s not just about preserving their own livelihoods and way of life, according to group president Cheryl Nielsen. It’s about protecting the special places in this area for visitors from across Australia and around the world. “This doesn’t belong to us. This is everybody’s,” Cheryl says.

The power and beauty of Wollemi and the Greater Blue Mountains is captured in a series of photographs by Ingvar Kenne for Wilderness Journal, evidence of the urgent need to protect these ancient and fragile landscapes.

In 1994, David Noble, a Field Officer with the NSW Parks and Wildlife Service, was exploring a canyon deep within Wollemi National Park with two friends. Up ahead was an unusual-looking tree he couldn't identify. Here in his own words, David—who still works in the Blue Mountains as a Ranger—recalls a famous moment of discovery that would go on to become one of the most significant botanical finds of the 20th century.

“It was the 10th of September 1994 when I first saw the pines; I was walking up into the canyon along a creekline with my two friends, Tony and Michael. We’d abseiled down into the canyon further upstream as part of a day-long expedition. I remember feeling intrigued as to what this strange-looking tree species was up ahead. It was dank and cool in the shade of the canyon. Under the pines there wasn’t much understorey and it was quite open, so we sat under these odd-looking trees for lunch. I remember commenting that they were peculiar-looking, but the conversation turned to how we would get out of the canyon to make it back out of the wilderness before dark.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but this tree went on to become one of the most significant botanical discoveries of the 20th century. I had studied botany as part of an environmental science degree at Charles Sturt University in Bathurst, and because I couldn’t identify the trees, I collected a small leaf from one, perhaps six inches in size. I took the leaf to naturalist Wyn Jones who worked for the National Parks and Wildlife Service at the time. Being a busy man he placed it aside and said he would get back to me. A few days later he asked whether the leaf had come from a shrub, but when I told him it was from a large tree his interest grew and he insisted I take him to see it.

“It took over a month before it was realised the tree was something remarkable and unknown. It was amazing that something this big had remained unnoticed for so long, and just a couple of hours out of Sydney. It was a feeling of sheer excitement and accomplishment that my knowledge of botany had helped identify a new species. The fact that the trees have survived for so long and hung onto life in a small remote canyon, protected from fire and drought, is fascinating. The bark is distinctly unique and on the mature trees it looks like chocolate crackles.

“The age of these pines, which date back to the time of the dinosaurs, shows the importance of preserving large areas of natural land as national parks and wilderness areas for future generations to explore and maybe uncover more of their secrets. Indeed, there are so many places in Wollemi that have not been visited by the right person. Many people have likely walked right past the Wollemi pines but just didn’t realise they were something new to science. There could be many secrets like this still to discover out there in the Blue Mountains.

“I still get out into the national parks to explore, but not as much as I would like due to family commitments. There are still some canyons that I have not been to and I would like to explore one day. The last time I saw the Wollemi pines was in 1995, I have not been allowed to visit them since; the threat of pathogens adversely affecting the trees means people can only go for scientific reasons; plus to avoid trampling and human impacts, the location is kept secret.

“The fires of 2019-20 were so devastating to so many places it was hard not to feel for the bush being destroyed; there was a sense of despair. I knew the Wollemi pines would be okay as they had been burnt before and regenerated. However, it is more the frequency of fire that’s an issue, and whether another fire will impact the pines within the next 10 years. The Wollemi pines will be safe provided humanity does not interfere. Climate change is the big agenda item that needs to be addressed soon. Unfortunately humanity seems to be concentrating solely on economic growth.

“I like to think that my discovery made people realise that there are still discoveries to be made in remote wilderness areas. Now that the species has been propagated all over the world, in botanic gardens and people’s own gardens, the Wollemi pine will survive long into the future, and people can watch them mature and change, and develop their distinctive characteristics.”

The Blue Mountains are home to a host of endemic, rare and beautiful animals. The World Heritage Area is a place where new life is still being discovered by scientists, but where we also stand to lose some of our most iconic species. Here four specialists describe the animals that are the focus of their work, including a new spiny crayfish, the spectacular giant dragonfly, the critically endangered regent honeyeater and some hardy koalas.

Dr Ross Crates, Australian National University

Regent honeyeaters (Anthochaera phrygia) are beautiful looking birds, one of the most spectacular in Australia in my opinion. When many people see them for the first time in the wild they are surprised at how yellow their wing and tail feathers are. They really are as impressive as the bird books would have you believe.

I'm fascinated by the sad fact that regent honeyeaters have declined so rapidly. There are now thought to be only between 150 to 300 left in the wild. What exactly is it about their biology that has made them so vulnerable to population decline over the past 60-odd years? This was really the central question to my PhD, along with the added question 'What can we do (if anything) to save them from extinction?' It was a combination of the challenge they present, the absolute beauty of the birds, the opportunity to explore some amazing parts of the Blue Mountains and beyond, and hopefully have some positive impact on the conservation of the species that drew me to regent honeyeaters.

Honeyeaters pollinate trees. This is their primary 'ecological role' within the Blue Mountains. When breeding, the birds will move from tree to tree and ship pollen around as they reap the nectar rewards, but we also know that these birds are able to travel hundreds of kilometres, which means they have the ability to provide long-distance gene flow to widespread eucalypt species such as yellow box and mugga ironbark.

Regent honeyeaters are also habitat specialists—they only occur in the best quality areas of woodland. The presence of regent honeyeaters (especially breeding) is as good a sign as you can get that a patch of woodland is of excellent quality, probably supports a whole host of other threatened species and should be managed and conserved accordingly. The regents can be found in national parks like Wollemi, Blue Mountains and Goulburn River.

The best time to see or hear regent honeyeaters is in early spring; the birds typically arriving at their breeding areas in early to mid August. The males spend a week or two at least being very vocal, establishing their breeding territories, impressing females. Once breeding commences, the birds go almost completely silent until the juveniles are totally independent from their parents.

Severe habitat loss is by far and away the main driver of the species' decline. Regent honeyeaters feed on and breed in association with gum trees that grow on fertile soils. These soils also happen to be the ones farmers are looking for to grow crops and graze livestock. It is estimated the regent honeyeater may have lost over 90% of its original habitat. As I drive around south-eastern Australia looking for these birds, the scale of habitat we have lost over the past century beggars belief.

Unfortunately, habitat loss has been compounded by competition with other bird species for the remaining habitat. In some ways, if you funnel all the birds into 10% of their original living space, it is not surprising that something is going to give. Regent honeyeaters are smaller than many of their rival species such as noisy miners, red wattlebirds, noisy friarbirds and musk lorikeets. Historically, their strategy would have been safety in numbers, but what we are seeing is that flocks are becoming smaller, which reduces an individual’s survival and breeding success. This then leads to smaller and smaller flocks, where you essentially end up in an extinction vortex.

Because regent honeyeaters are particularly dependent on the availability of blossom to breed, they are also hit hard by droughts, because the eucalypt trees don't flower during drought. As climate change kicks in and droughts become more frequent and intense, it is only going to reduce the breeding opportunities for the birds.

Our work is extremely field-based. We have established a new monitoring program that aims to locate the birds during the breeding season. When we find them, we monitor nests (sometimes with cameras), record songs and tag some individuals with small coloured leg bands. The aim is to identify these really important breeding areas and find out exactly why these birds are having such a hard time.

There are many things being done to protect the regent honeyeater. The first two are habitat restoration and protection of existing habitat. Our research has shown that breeding success rates are at an all-time low, so we are now trying to implement nest protection measures. These involve culling noisy miners, which are a major threat to regent honeyeaters, and placing plastic collars around nests to stop possums and goannas accessing them.

We also work closely with the captive breeding program (being run by several institutions including Taronga Zoo), not only to teach the captive birds to sing more like their wild counterparts, but also providing the reintroduction program with really detailed information on where the wild birds are occurring, so that the captive-bred birds can be released in locations and at times where they have the best chance to mix in with the wild birds.

The birds are having a relatively successful season this year, and next year promises to be another cracker given how much rain we have had. A lot needs to go right to save regent honeyeaters from extinction. However, there is still hope, the birds are still out there breeding and we are getting better at implementing conservation actions all the time.

Dr Ian Baird, Conservation Biologist

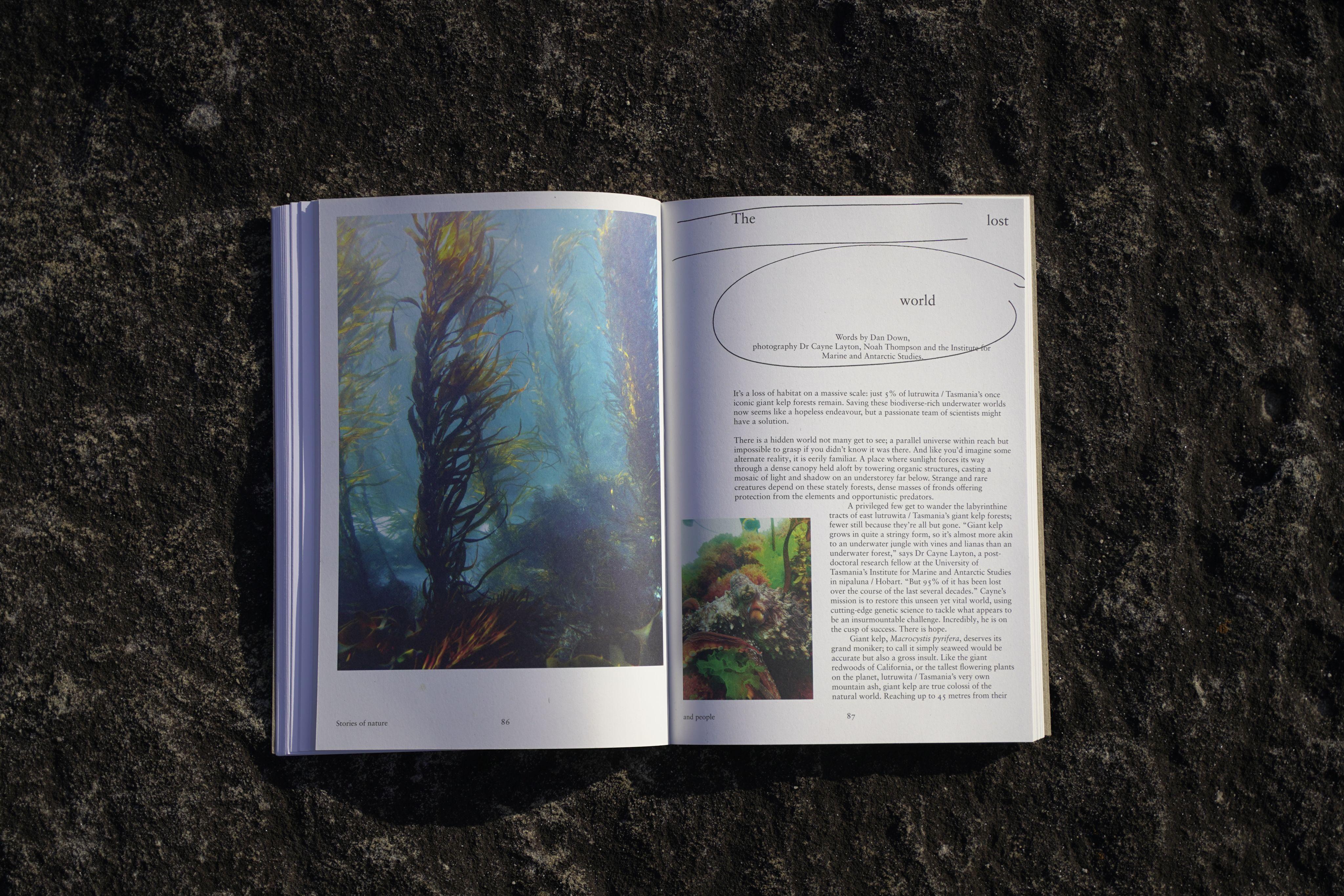

The endangered and unique peat swamps, or ‘hanging swamps’, of the Blue Mountains are home to an ancient survivor from the age of the dinosaurs. The endangered giant dragonfly (Petalura gigantea) has remained virtually unchanged since the Jurassic period. It’s another example of just how ancient a landscape the Blue Mountains is, along with that of another famous living fossil, the Wollemi pine.

With a wingspan up to 12.5cm it is a formidable predator, although one which is rarely seen. You can really imagine them flying around in the time of the dinosaurs.

Female dragonflies lay their eggs in the saturated peaty swamp soils. After hatching, the larvae (nymphs) excavate deep burrows down to below the water table. Here they live for at least six years, maintaining their burrows while feeding on small invertebrates, before climbing out and transforming into adult dragonflies. During late spring and summer the adults prey on other flying insects, find mates, lay eggs and continue the cycle. The dragonflies need a high water table and saturated soils in these peat swamps for the eggs and larvae to survive.

Much of the giant dragonfly’s peat swamp habitat has been destroyed or is under threat from longwall coal mining or urban development, while climate change poses a serious threat. We need to protect the Blue Mountains' remaining peat swamps to ensure the survival of this remarkable, ancient animal that outlived the dinosaurs!

Rob McCormack, Astacologist

I run the Australian Crayfish Project, a privately funded initiative run entirely by volunteers. We conduct research into these invertebrates to increase the knowledge base on all our crayfish species to ensure their habitats are protected and conserved.

Much of our work involves surveying creeks and streams across Australia to identify the crayfish present. We gather valuable information on their distributions, biology and ecology, but we also find completely new species. It's the discovery I like; going to remote areas, surveying creeks and learning what species are there, be it a new distribution of a known species or something entirely new to science.

A good example is the Cudgegong giant spiny crayfish (Euastacus vesper) found in the upper Cudgegong River and its tributaries that run through private properties and the Coricudgy State Forest that abuts Wollemi National Park. Shane Ahjong from the Australian Museum and I described this new species in 2017, like other Euastacus species it can develop lovely pink/purple claws, measures about 250mm long and has spines all over its thorax as its common name suggests.

The Cudgegong giant spiny crayfish relies on permanent water, it has no capacity to survive drought. In late 2019 and early 2020 mega bushfires devastated the forests of NSW. These fires were the result of the preceding three-year extreme drought. When drought occurs the streams dry up and the small population of E. vesper is significantly reduced, only a remnant population survives in the deeper pools that retain some water. Luckily in February 2020, the rains returned and the fires were put out, the streams refilled and those surviving adults can hopefully breed up to repopulate the stream.

It’s early days yet, we haven't had time to see if the species has recovered. However, unfortunately E. vesper has little going for it; another giant spiny crayfish E. armatus has been stocked into the nearby Dunns Swamp Lake and it is competing with E. vesper. Illegal recreational fishing in the area is also devastating the small E. vesper population; recreational fishers are unknowingly targeting endangered Euastacus species thinking they are common yabbies.

The wealth of information we are compiling year after year will be paramount towards the conservation of all Euastacus species in Australia and especially those in the creeks and streams of the Blue Mountains. The Australian Crayfish Project will continue well into the foreseeable future, we don’t know what we’ll find out there, but every day in the field expands our knowledge base on our unique and incredible crayfish species.

Kellie Leigh, Executive Director, Science for Wildlife

At Science for Wildlife we are working out where koalas occur in the Blue Mountains, which habitats they use, and what threats they face. The general consensus used to be that the Blue Mountains area wasn’t important for koalas, I guess because a lot of it is sandstone country. I started the project back in 2013 after the bushfires that year, because koalas were seen in the Lower Blue Mountains for the first time in decades, coming out for water. Since then we’ve uncovered some significant populations of koalas.

We carry out surveys to work out where the koalas are living, including using koala scat detection dogs. The forests can be very tall and the country is rugged, including tall blue gums and forests with thick canopies, so you can’t just walk around and look up and count them. When we find koalas, we give them a health check and then fit them with a tag to track them. From there we collect information on which tree species they prefer, what their breeding and mortality rates are like, if they get disease, and a bunch of other information.

The Blue Mountains is a really fascinating site, as one of the main World Heritage values for the area is the outstanding diversity of eucalypts, and so koalas have around 100 different species of tree to choose from, more choice than anywhere else in the country!

In southeast Wollemi, the range of koalas appears to extend beyond the national park, up along the Colo River towards Mellong, and down into the Hawkesbury developed area. Based on sightings and our data, they would occur to the west and east of where we surveyed as well.

We haven’t yet surveyed where there is a plan for a potential coal release area at Ganguddy-Kelgoola, but I have little doubt the koalas would be there. We receive regular koala sighting reports from around Lue and Rylstone every year, and it makes sense they would occur in the more intact habitats closer to Wollemi. That area, and out to Mudgee, is actually a priority area we’d like to get into to do some surveys. There is definitely koala country around there.

Aside from our work around the Blue Mountains, we’re undertaking some collaborative genetics work looking across the full koala genome on a national scale. We assessed koalas right across the species range from South Australia to northern Queensland. It turns out that koalas in the Blue Mountains had the highest level of genetic diversity out of the 21 populations we looked at! If you want to conserve any threatened species it is really important to maintain good genetic diversity; that is what allows a species to adapt to selection pressures over time.

We had a really good news story for koalas in the Blue Mountains but the Black Summer Bushfires were devastating. We had five sites identified that we wanted to survey. Four out of the five sites were burnt, with between 75% to 100% coverage by fire. The enormity of that threat is what drove us to go in and take those koalas out from Kanangra-Boyd, in front of approaching fire, and get them to safety at Taronga Zoo who took them in for us. The risk was that we’d lose the entire koala population from that area.

Besides fire, the most significant threat to koalas outside of the national park system is habitat loss and then a range of associated impacts: a lack of food trees to sustain them, domestic dog attacks, vehicle strikes, and chlamydial disease is a big threat in a lot of areas. Mining can cause habitat loss and is obviously of great concern. It can impact the water table, which is a problem because koalas typically get all of the moisture they need from the leaves they eat and so access to water for the trees is vital.

It has been particularly tough since the Black Summer fires, but there is still some hope. The Greater Blue Mountains World Heritage Area is over 1 million hectares in size and in it we’ve found a bunch of rule-breaking, resilient koalas. I kind of imagine them in black leather jackets riding Harley-Davidson bikes. They’re busting all of the rules we had around koala ecology—using tree species and soil types we didn’t know could sustain them, living above the modelled climate envelope for koalas at over 1000m, and some are chlamydia-free like in Kanangra-Boyd.

In terms of conservation priorities, one key concern is that we need to maintain momentum. After losing 3 billion animals to the bushfires it will be a long road to recovery. The fires were a game-changer and conservation management will have to be more hands on under climate change. Maintaining the intact habitats we have left is critical.

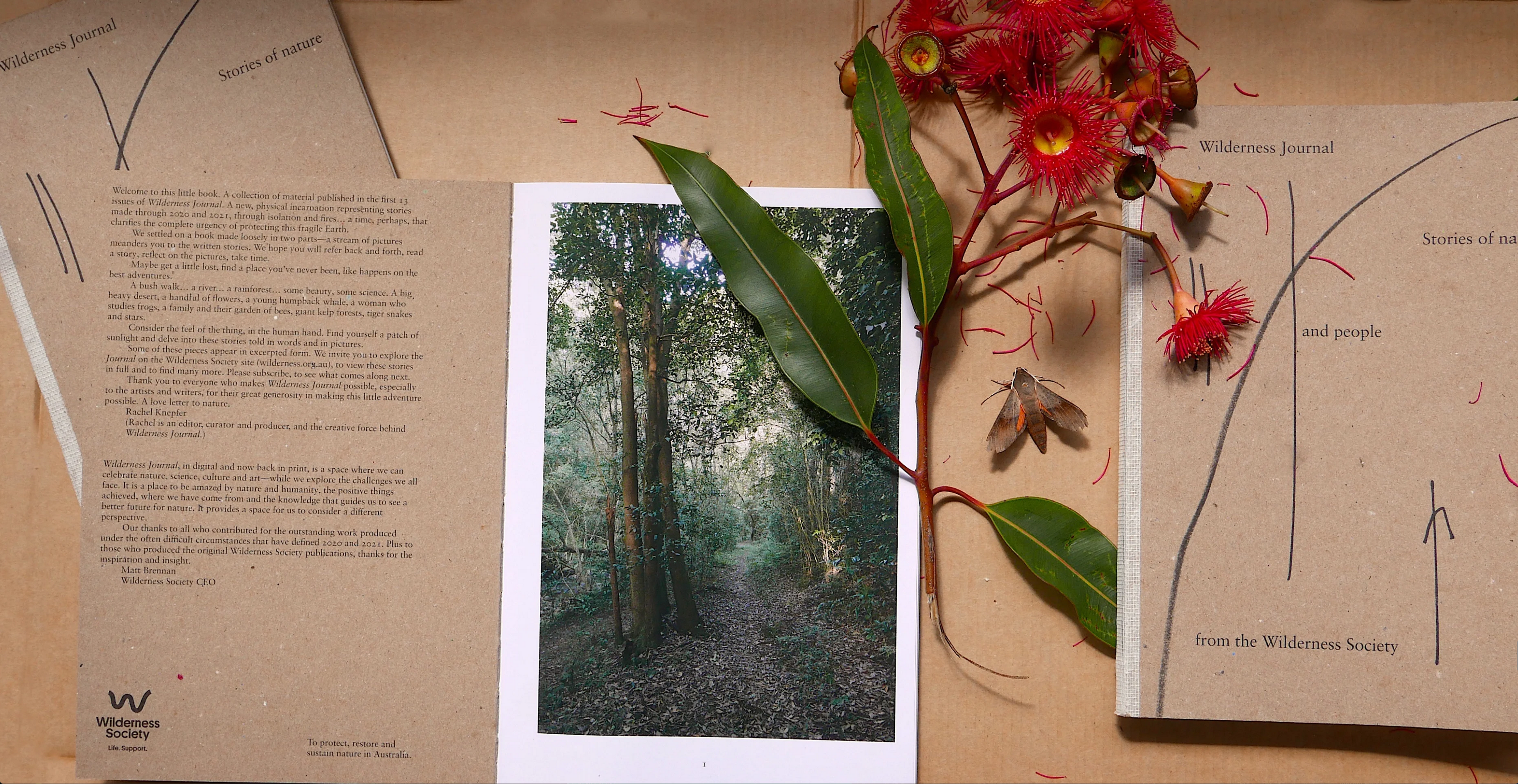

Rachel Knepfer, editor, curator and producer, introduces our new book. Together with a love of good pictures and stories, Rachel has a deep commitment to the protection of our natural world. The former Photography Editor at Rolling Stone magazine in New York brings her international publishing experience to this ongoing project. Photograph above: Rachel Knepfer.

Dear Friends,

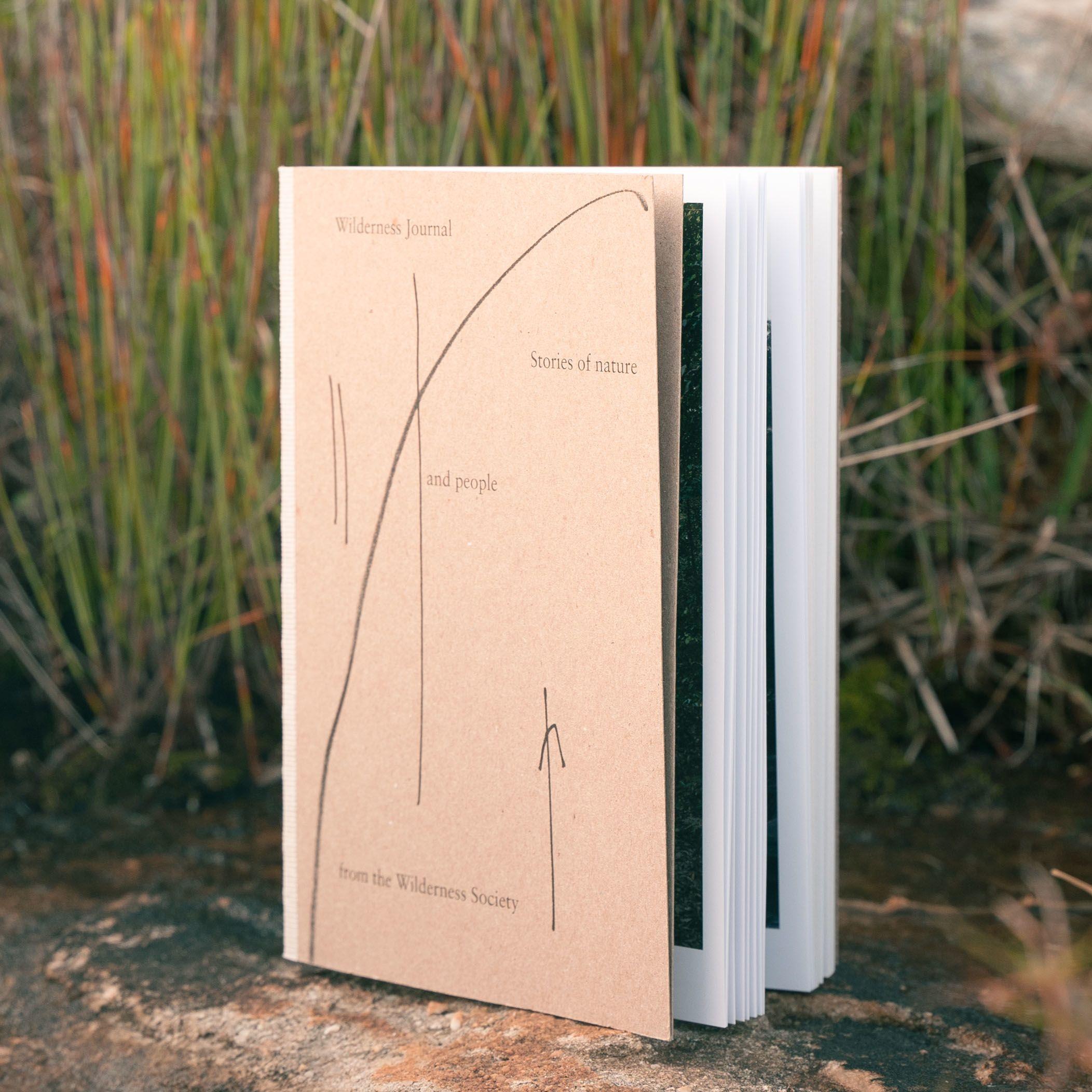

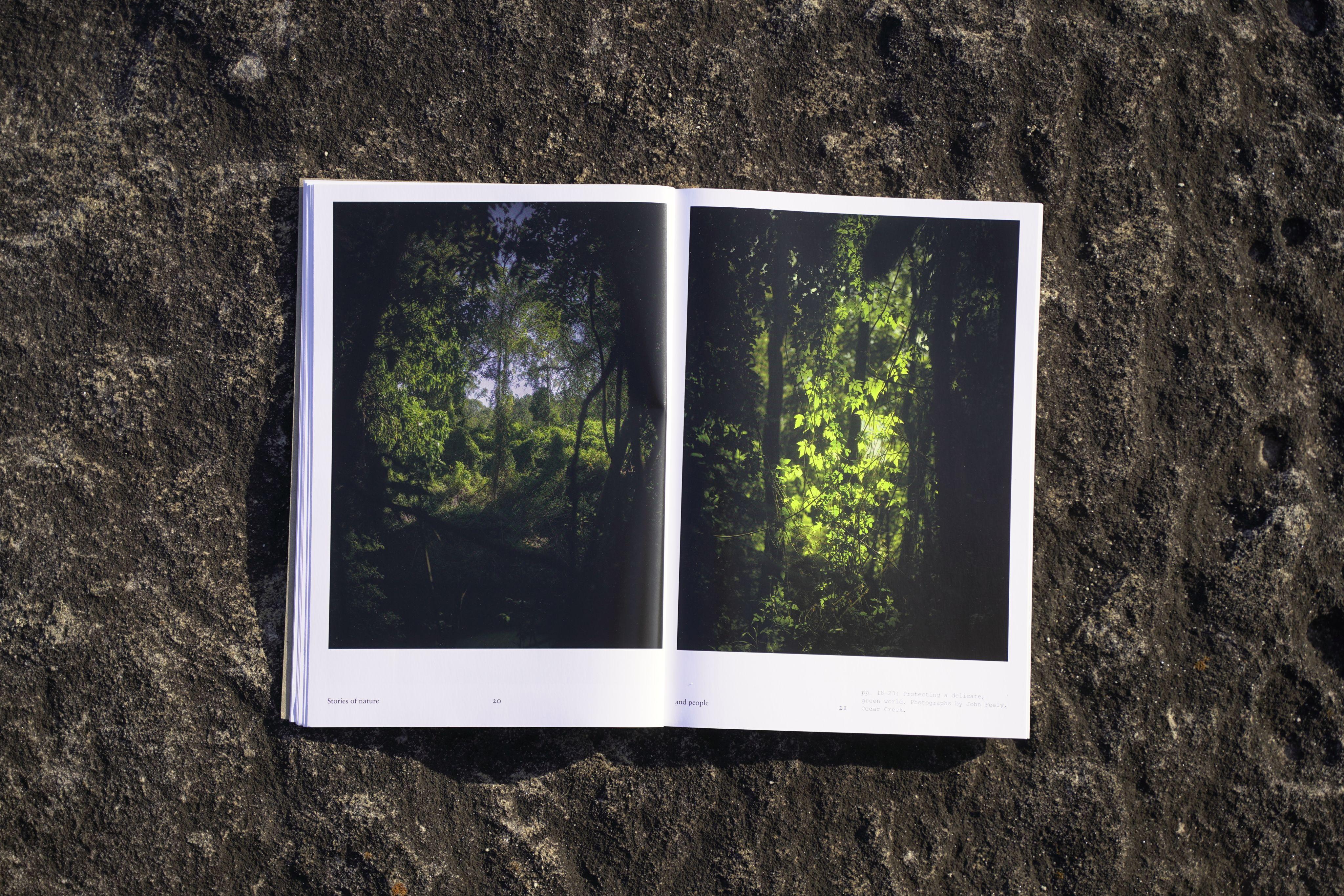

We've made a book. Wilderness Journal: Stories of nature and people. A collection of material published in the first 13 issues of Wilderness Journal. A new, physical incarnation representing stories made through 2020 and 2021, through isolation and fires… a time, perhaps, that clarifies the complete urgency of protecting this fragile Earth. We invite you to take some time with the book, consider the feel of the thing in your hands, maybe get a little lost, find a place you’ve never been, like happens on the best adventures. A bush walk… a desert, a river… a rainforest… some beauty, some science.

To bring this book to life, we worked with esteemed book designer Stuart Geddes, who has shaped the material into something classical and beautifully unexpected. We’ve worked hard to make it the best thing possible, with the very lightest footprint.

We thank the brilliant and generous contributors to Wilderness Journal, some of the world’s finest photographers, scientists, artists, illustrators and writers—all of whom have given their time and their talents as a force for protecting nature.

RK, 1 December 2021

(Limited run, ISBN: 978-0-646-85140-2, 128pp, section-sewn, 100%

recycled paper, and printed and bound by three local businesses in Naarm

/ Melbourne)

A Wollemi pine (Wollemia nobilis) sapling photographed in 1995 by David Noble in undisclosed location in Wollemi National Park.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.