Wilderness Journal #030

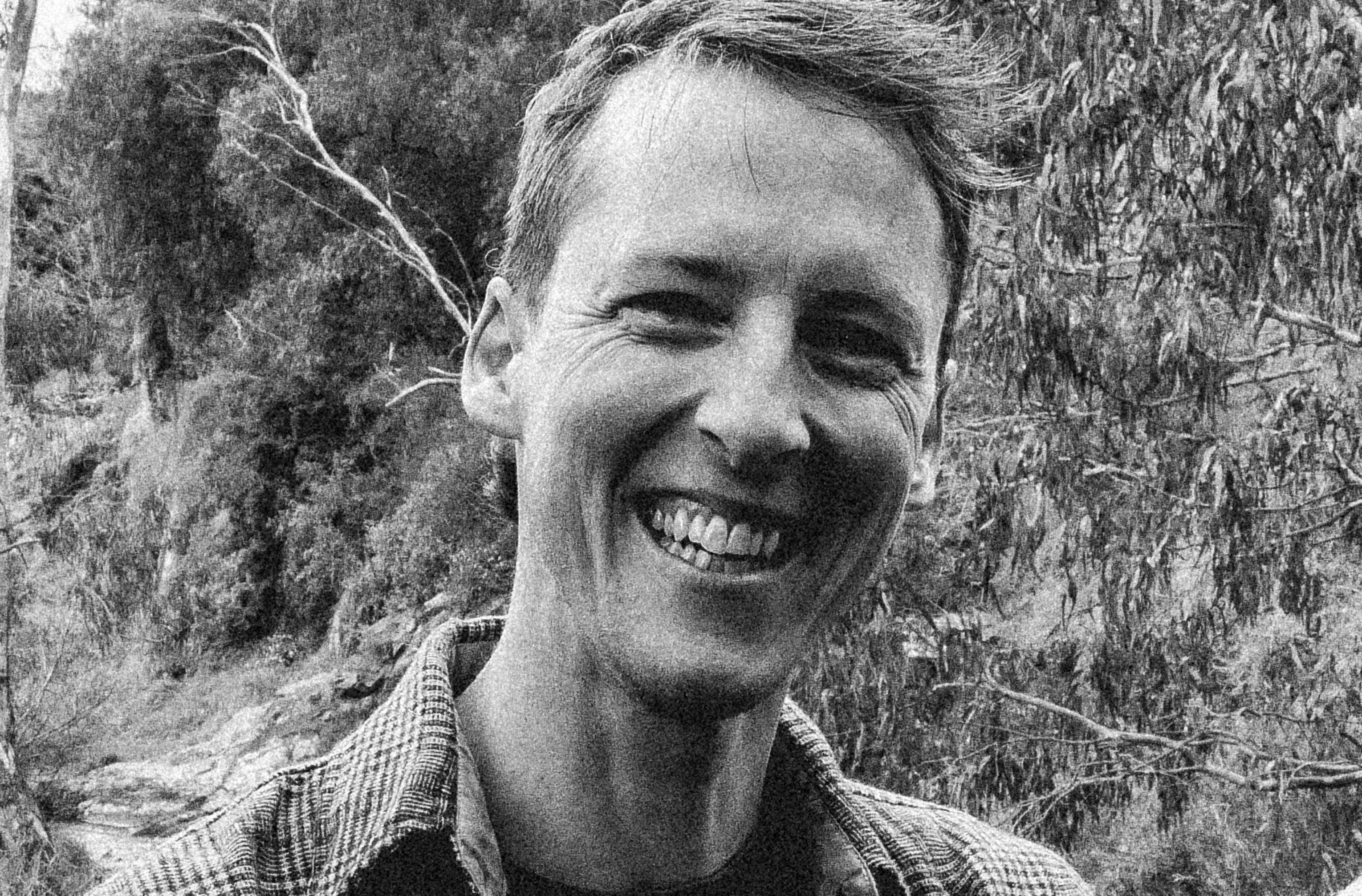

Bob

Brown, co-founder of the Wilderness Society, introduces this special

Franklin edition of Wilderness Journal—a look at the past, present and

future of the campaign that saved the Franklin River, lutruwita /

Tasmania.

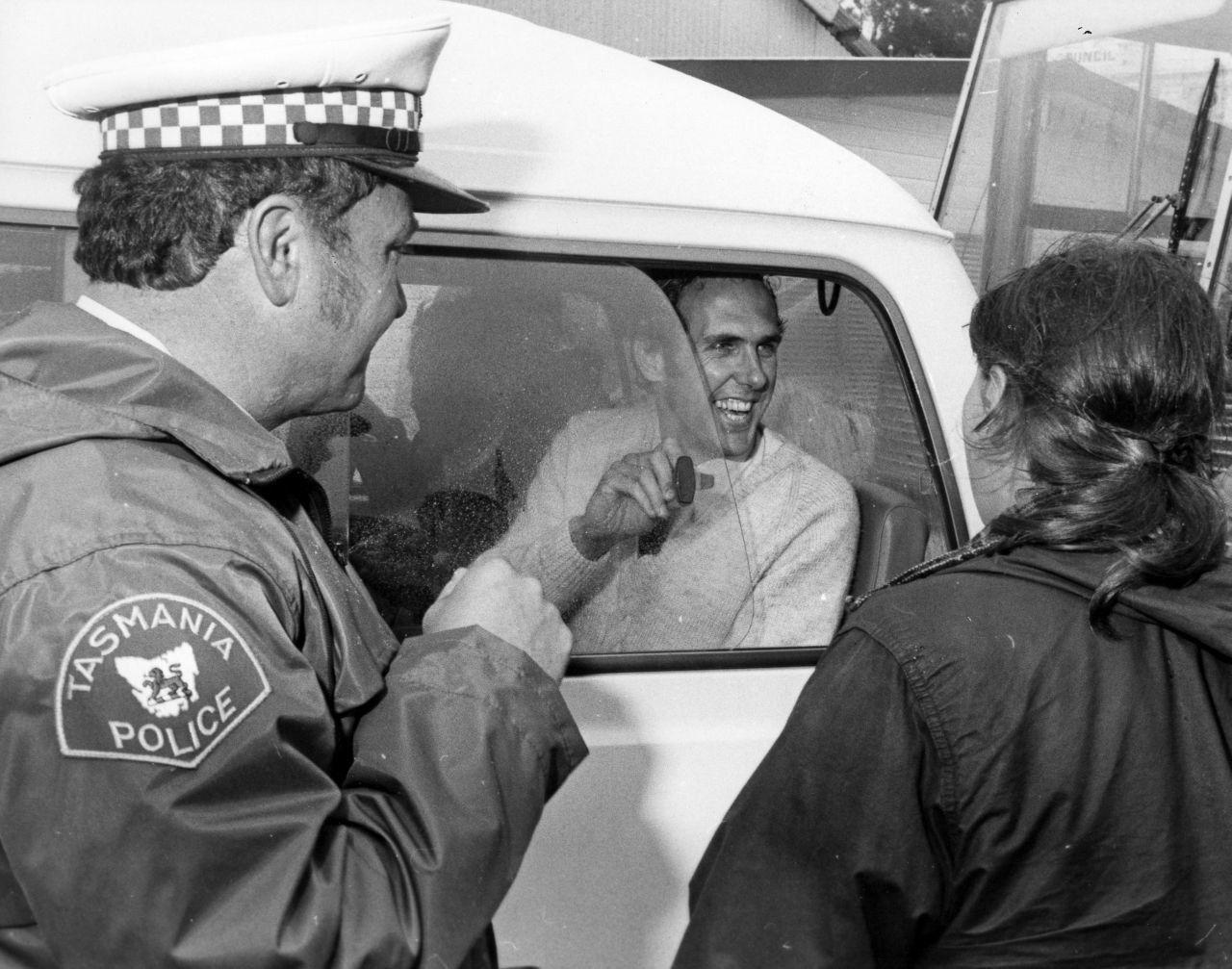

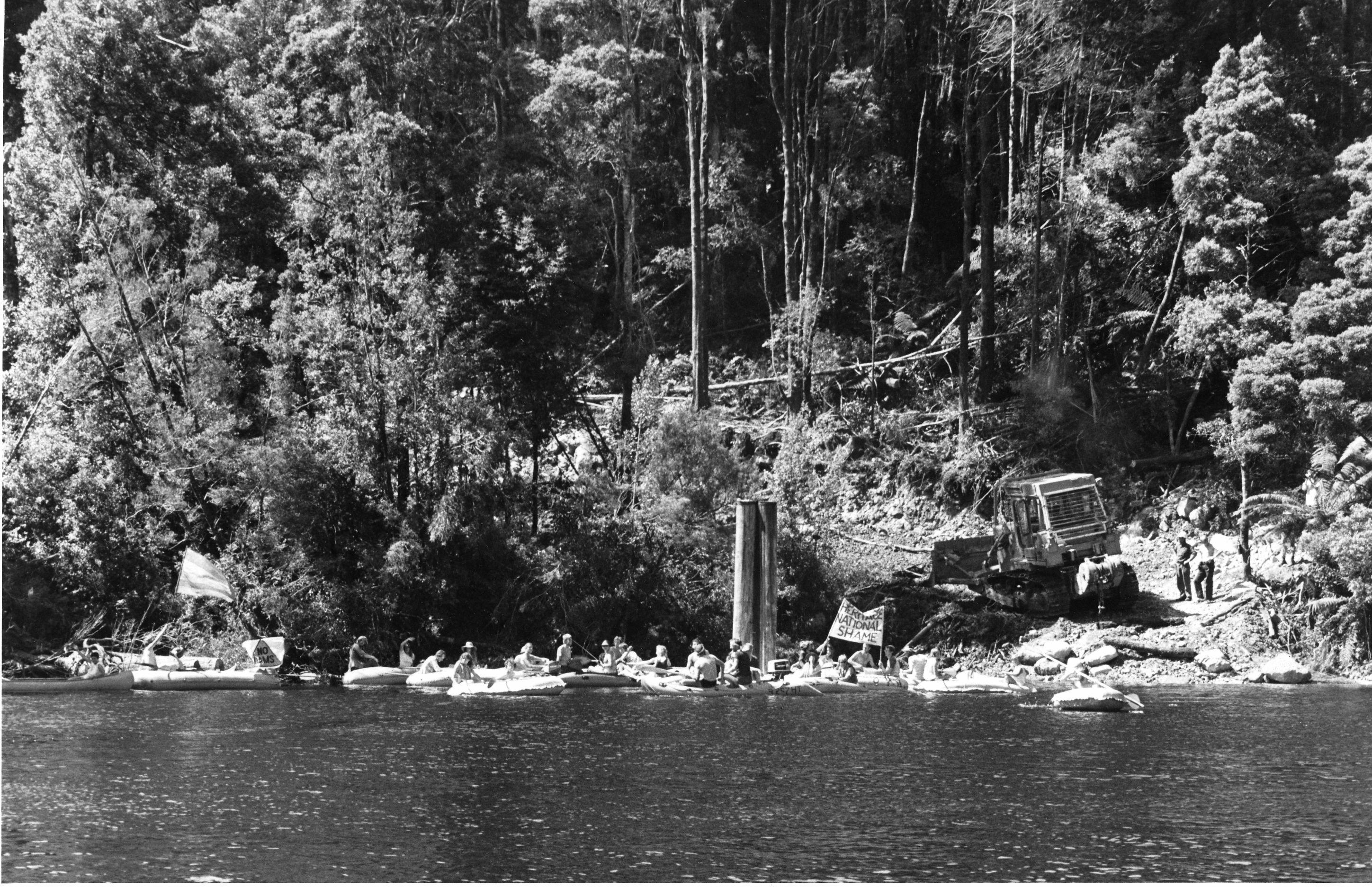

(Photograph above, protesters on the Franklin, 1983)

The campaign to save the Franklin River took seven years, 1976-83. Notable throughout were the efforts of the Tasmanian Wilderness Society (which became, in 1984, ‘The Wilderness Society’) to get people to raft the river and see it for themselves. It takes a month to organise a good rally and seven years proved a good lead-up for a national environmental showdown.

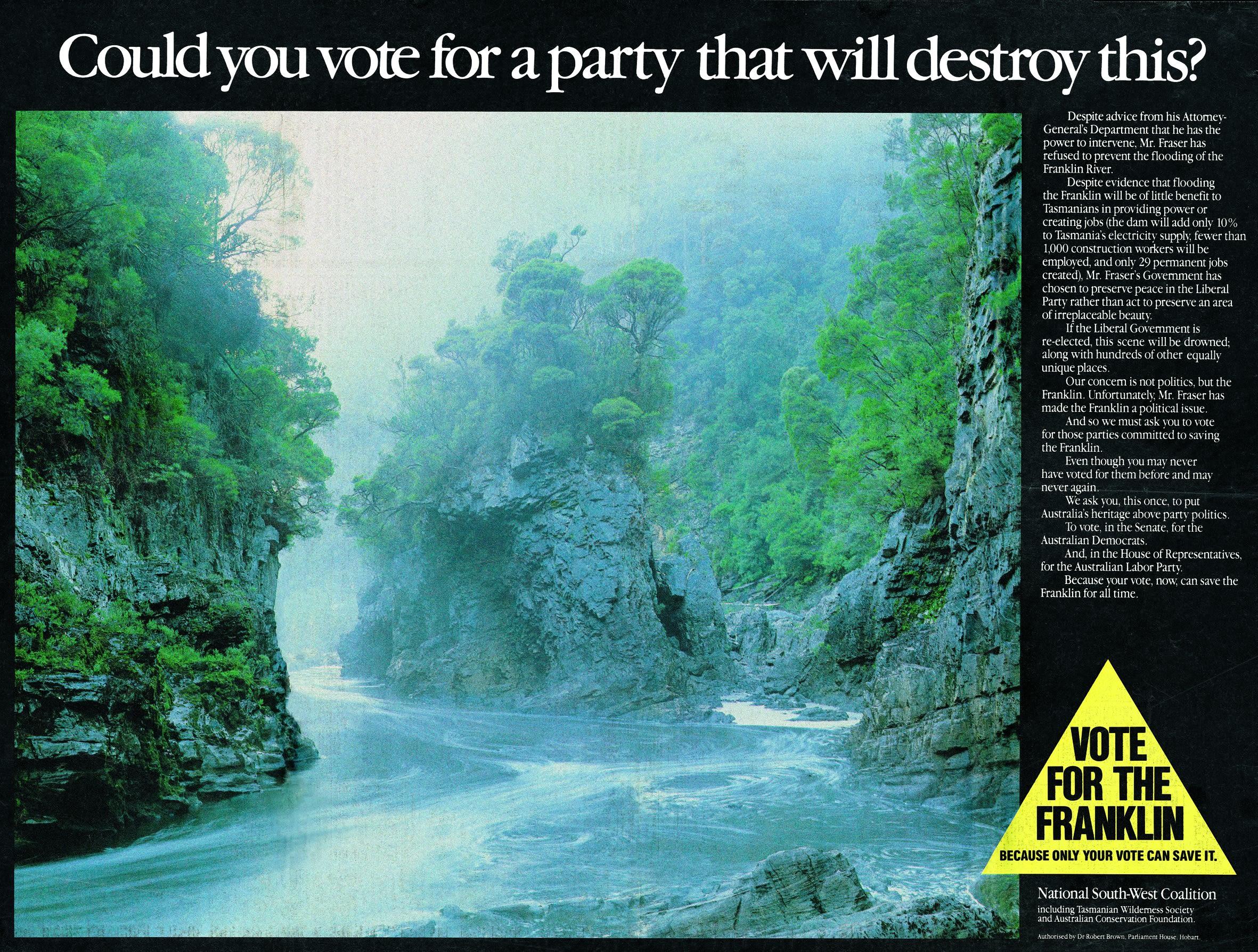

When ‘the whispering bulldozer’ Tasmanian premier, Robin Gray, was elected in May 1982, and most of us Save-the-Franklin candidates lost, it seemed nothing could rescue the river from the Hydro-Electric Commission’s proposed four dams. By that July, the bulldozers were rumbling into the Franklin valley. However, in July 1983, exactly a year later, works were stopped when the High Court ruled that, in upholding the World Heritage Convention, Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke’s government could overrule Gray.

Three big factors were at work in that amazing year of 1982-3, which saved the Franklin 10 years after Lake Pedder was drowned by the HEC. The first was the advent of colour television: TWS campaigners worked hard to get the beauty of the Franklin into every Australian's living room. The second was the entry into the campaign front ranks of the Aboriginal community after the rediscovery of their ancestors’ living quarters in Kutikina Cave beside the lower Franklin. The third was the blockade which was deliberately staged in the remote wild rivers region so that, in almost every shot, the rainforest-flanked riverine beauty—and then the bulldozered ugliness—was backgrounding the human drama as hundreds of good people were arrested and many jailed before a national audience. These scenes were a compelling factor for voters to back NO DAMS candidates at the March 1983 federal election, which saw Hawke swept to power and announce NO DAMS in Tasmania.

I thought this must be the start of a new age of environmental protection in Australia. How wrong was that! The corporate extractors of nature went into overdrive with greenwash, vilification of environmentalists and capture of parliaments and, as we all know, the twin spectres of the climate emergency and species extinction crisis are now tumbling out of control. Yet there is an intelligent defiance in the air. We cannot know what the future of life on Earth will be and whether humankind is about to end its own era of great expectations.

But this I do know. Back in 1982 the Franklin was lost. We at TWS had nowhere to go. Both Houses of Parliament, both parties in Tasmania, all three newspapers, the unions and big business and, of course, the omnipotent HEC backed the dams and works got under way. The pre-Hawke federal government refused to intervene and TWS’s first appeal to the High Court failed to even get a hearing. But, we decided, while the river remained flowing free to the sea our campaign would flow and grow with it. And look what happened!

In 2022 it seems the whole planet’s biosphere is in trouble. However the global campaign by H. Sapiens to save it from ourselves is growing and we TWSians are so lucky to be alive and taking part. Whenever I find the prospects daunting, I turn my mind to the dark days of the Franklin campaign and get great pleasure from remembering how we opted for action over despair.

—Bob Brown, September 2022

Franklin, a new documentary from director Kasimir Burgess, premiered at the Melbourne International Film Festival to much acclaim in August. It follows environmentalist Oliver Cassidy as he retraces the journey his late father made down the Franklin River in the early 1980s to join the Blockade. We spoke with Oliver about his deeply personal, dangerous yet spectacular rafting expedition and the film's producer Chris Kamen about some of the challenges faced bringing the story of the Franklin to a new audience.

Photographs by Jamie Wdziekonski

What was your motivation for making this film?

Chris: It's a story that I felt compelled to try and get to a new generation. I'm very excited to celebrate the achievements of the older generation, to pay our respects and give thanks to the activists who were part of the campaign. But I was perhaps more motivated to get the story of the Franklin to a younger audience who've never heard of it.

I was born in the year that the Franklin was saved, so it wasn’t part of my life. It was a real revelation to discover this incredible story of national significance; Australia's most significant environmental campaign.

I think a big part of depression and anxiety today comes from this overwhelming burden we all feel about the environment. And so as a filmmaker, if I can bring the power of this story to a whole new generation of student strikers and young activists, I hope that it will lift us all a little bit. We're going to have to be strong to confront what's coming.

What challenges did you face shooting a film on such a remote and wild river?

Oliver: It was full on, especially for me because I'd had gender affirming surgery in July, and we shot this in November.

I had all these great plans about getting to be as fit as I'd ever been in my life to tackle the river. And everything kind of went wrong with my body; every injury that I'd ever had in the past flared up. I got the flu; I ended up in hospital on a drip with a crazy temperature just because I was pushing myself too far, too hard after having the biggest operation I'd ever had.

I wanted to represent myself accurately; I want this film to be something that will help the environment movement and the issues that we're dealing with in the world. And I couldn't do that if I had stayed in the closet and created something that I couldn't bear to watch myself.

Chris: I love getting out in nature and so I loved the actual shoot. It was a real privilege to take a film crew down the Franklin to show its grandeur with all of our high-tech cinema, 4K cameras and drones and so on.

In the visual language we are trying to communicate the timelessness of this place. It's just incredible how slow and remote it is.

To convey the remoteness of this place on screen was a real challenge because you can say that you're miles from anywhere, but it's hard to really feel it in cinema. So we tried to use aerial photography to show the vastness of the river and the landscape it sits in.

Chris, what was your understanding of the Franklin and the Wilderness Society before working on this film?

Chris: I discovered the story of the Franklin campaign when I was studying law, because the High Court case continues to be one of the most significant legal cases in Australian history. I thought it was a really inspiring story; a time when activists prevailed and launched a big win for the environment. I guess I found it inherently dramatic and so thought it would make a good film. I was wondering why I hadn’t heard much about it in my life, because I guess we're facing climate and environmental catastrophe, and this is a good news story.

I found it very powerful to understand where characters like Bob Brown came from, what their political coming of age was. It took me down a rabbit hole.

What were your favourite moments from being on the river?

Oliver: It's the feeling of the richness of that place. It felt life changing. Listening and watching and being one of a 100,000 species. Whatever it is that you're dealing with out there in the world beyond, I felt safer on the river. I felt like I was really where I should be.

Leeches are everywhere, but I also saw some amazing lampreys—these incredible creatures. One I saw just swimming along like it was a little sea snake, and then another, pinned onto a cliff face.

It's a whole section of existence, of life and species that we just have such little direct exposure to.

Chris: For me it was the Irenabyss [Chasm of Peace], you come down a set of rapids and then it just opens into this incredibly peaceful, slow-moving passage through caves. And I always wanted to make sure we captured that; I'm really proud that we were able to pull that sequence together because it’s my favourite part of the river. I could sit there on those rocks and just watch the world go by forever. It's so peaceful; it's an incredibly emotive and powerful place to be.

How do you feel the activism of the Franklin shaped action today? What can it teach us about community?

Oliver: I recently completed the Wilderness Society’s community organising training back in May. As part of the course I realised that my ability to care quite so much about environmental issues had in fact diminished a little.

As a trans person, I have recently had to put more effort and vigilance into my own well-being and my own safety. And I feel that there is actually some wisdom in this. As the climate crisis worsens, we are going to experience more and more directly its impacts on our lives. For instance, we've seen the flooding that happened earlier this year and we've seen the bushfires from a couple of years ago, and people are losing their homes and livelihoods.

We need to be looking after ourselves as a community first in order to be able to step up and take those big acts to make things better.

Apply the oxygen mask to yourself before assisting others!

Chris: The Franklin campaign was a formative moment for Australian consciousness in terms of the environment becoming a major consideration in how we look after this country. It's left an indelible mark on the older generations who lived through it.

The Franklin isn't as big a part of the mythology for younger people as I would expect. But I'm hoping that our film can help with that. For young activists today, for them to know about what's happened in the past, for them to feel part of the continuum of activism in Australia, I think that's powerful for young people coming into the environment space to be aware of what has preceded them. They're standing on the shoulders of others; they're not alone.

Oliver: Something that I got from speaking to the people that had been involved in the Franklin campaign is that there was never a guarantee that it was going to win.

From my side of the history, the campaign had always been won, so I never really had thought about it like that. But I now realise that that was the position that they were in, and they still thought it was worth putting themselves on the line to fight anyway.

And that's exactly where we are today. We have just as much a chance to win now.

Chris and Oliver would like to thank the Wilderness Society and Jill McCulloch, archivist in Hobart, for helping to make the film and source archive footage. Thanks to photographer Jamie Wdziekonski for his time and work.

Franklin is showing at select cinemas. Check out upcoming screenings.

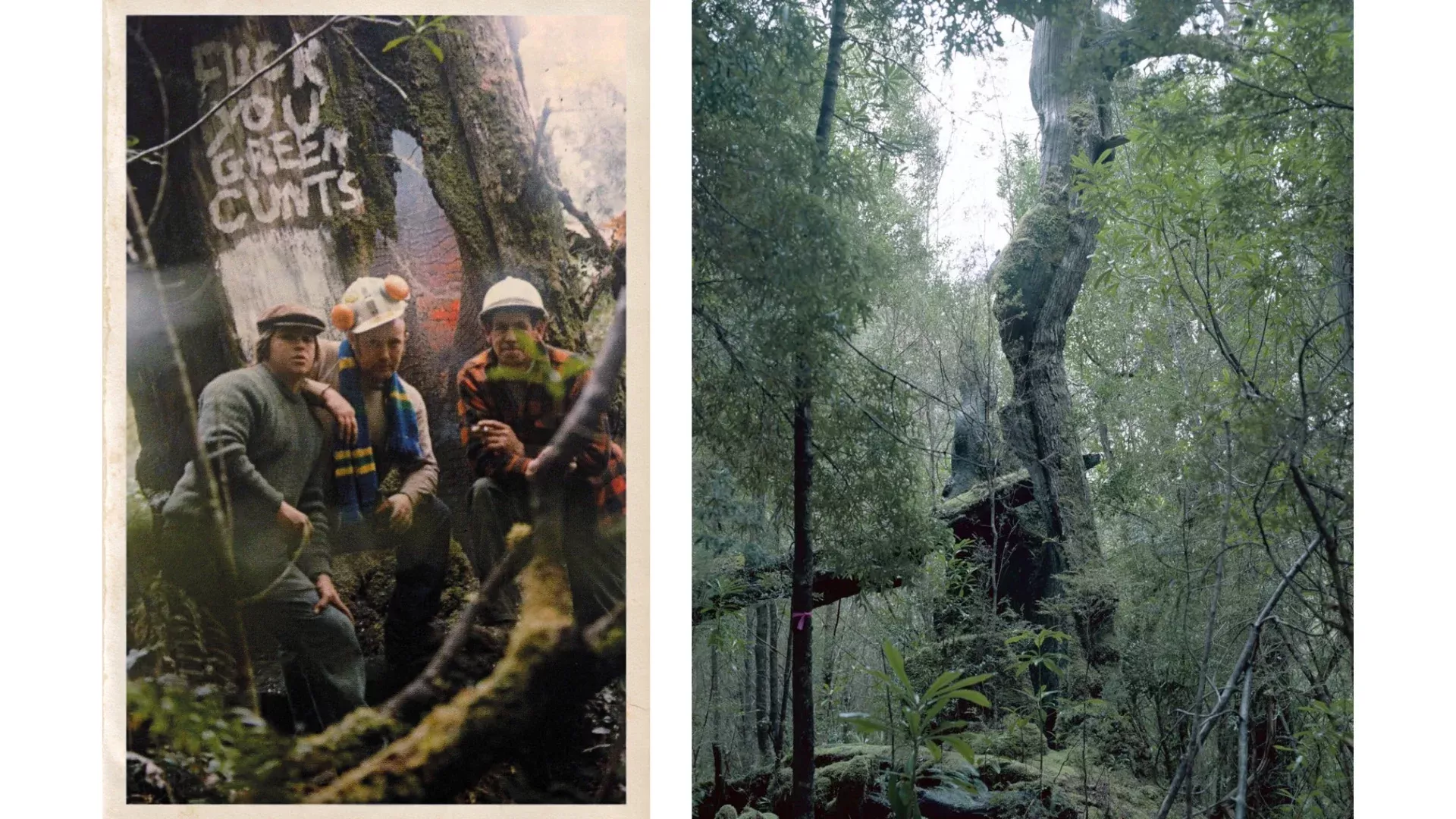

A 2,500-year-old Huon pine on the Lower Gordon, the Lea Tree served as a place for the Blockaders to gather, plan and celebrate during the Franklin campaign. Following victory for the campaigners, the tree was set alight by vandals in July 1983. The act was captured with a photograph of the burning tree. Photographer Noah Thompson travelled to the Lower Gordon and took a portrait of the Lea Tree. He juxtaposed it with the infamous 1983 photograph in his ongoing series, Huon.

Warning, bad language imminent: One of the following images contains offensive words, but it represents an important part of the Franklin story.

"After the sudden death of my grandmother, my grandfather left his family temporarily to work in the mines on the south-west coast of lutruwita / Tasmania. I never met him. He once told my mother he would ‘run over you myself’ if she stood in front of bulldozers in protest against the construction of the major and controversial dam project, the Gordon-below-the-Franklin Dam. The dam would flood a World Heritage-listed rainforest in the south-west and after ongoing protests and legal challenges, it was announced that the dam would not be allowed to proceed.

"Shortly after, a 2,500-year-old Huon Pine, known as the Lea Tree, was vandalised by pro-dam interests. A symbol for the conservationists, the tree was chainsawed, holes were drilled into it to pour oil into its roots and finally, it was set on fire. The trunk was scrawled with the words ‘F**K YOU GREEN C***S’ before the perpetrators photographed themselves in front of the still-burning tree. The resulting photograph was then sent to one of the conservation organisations.

"Huon is inspired by the conflicts we come into with one another over protecting or exploiting the natural world. The tensions that underpin these apparent dichotomies are not black and white but instead coloured by traditions, livelihoods and community. Reinforced by notions of how we want to live and the means by which we can, this work traces the marks we leave on the earth, ourselves and each other."

Huon will be published into Noah's first monograph by US based publisher Charcoal Press of The Charcoal Book Club in 2023.

What does the Franklin River mean for people today? For the First Nations community, the palawa, who have a deep connection to this Country? For the Blockaders who fought so hard to save it? For the scientist monitoring the health of the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park ecosystem? Writer Steve Madgwick traverses the Franklin in search of answers.

Words and photography by Steve Madgwick

“Sounds bloody amazing” is, unsurprisingly, a typical and germane reaction to my breathless anecdotes of gushing down the length of the Franklin River on a recent commercial white-water rafting expedition. Dumbfoundingly surprising, however, are the words which often follow: “Sorry, where did you say that is again?”

Born in the AB (After Blockade) years, most of my offending interlocutors consequently know close to zilch about the fabled river’s significance to Australia’s conservationist movement. If you think I hang around pathological ignoramuses, ask a Millennial or Generation Z-er (outside of the conservationist community) about the Franklin and report back. I was born in the year 11BB (Before Blockade), but my Franklin affinity is limited to vague childhood recollections of ‘No Dam’ stickers on my geography teacher’s car and time spent trying to decode the ‘Gordon-below-Franklin’ Dam conundrum. (Was the Gordon a magical underground river?)

Beforehand, I viewed my expedition with Tasmanian-based Franklin River Rafting purely through the lenses of post-lockdown adventure and work (as a travel writer). Ten days at the whims and caprices of this remote landscape, however, forced me into a deep dialogue with nature. Questions needed answers. As we (three guides and 11 passengers) plopped in our three big orange rafts—laden with food, shelter and warmth—into our entry point on the Collingwood River, a profound thought dawned on me and grew as the days went by: We are the introduced species.

From that moment under the non-descript Lyell Highway bridge to our rendezvous with a Strahan-bound charter-yacht on the Gordon River 10 days later, I counted only a handful of clues that humans existed at all: an old flyingfox and helipad at the proposed Fincham Crossing dam site (day 4); a helicopter hovering high overhead (day 5); and one discarded biscuit packet at a Lower Franklin campsite (swiftly picked up).

Naturally, rafting down an infrastructure-less river has its challenges (but is no means beyond those of reasonable fitness). At times, the sulky West Tassie autumn misbehaved like a mainland winter. The water temperature chomped through our wetsuits and thermals. The rain persisted for eight days, vexatious enough to thwart our attempt to summit Frenchmans Cap, which never truly revealed its magnificence from behind its cloudy cloak. The persistent precipitation animated Peter Griffiths and Bruce Baxter’s description of the Franklin as the “ever-varying flood” (title of their guide-book). On day three, the river level rose two metres overnight, enforcing a rest day and reinforcing that we were as reliant as toddlers on the guides’ esoteric experience.

We treated the Middle Franklin’s Great Ravine with pious respect. We meticulously portaged boulder-strewn sections of the Churn and Cauldron (referenced in ‘Death of a River Guide’) et al, where the force of the flow narrows treacherously into Grade 5 rapids, many with a history of fatality and misadventure. The guides ‘lined’ the rafts down these flashpoints while we scrambled over slick rocks and clambered up steep saddles to rendezvous downriver. Each night, we collapsed onto our Therm-a-Rests and wriggled into our minus-rated sleeping-bags, colonising nooks of riverside caves—often softly lit by glow-worms—or huddled under communal tarpaulins in riverside rainforest.

Whitewater rafting is the only realistic means by which to see the more remote and sensitive parts of the Franklin, so naturally questions arise about the commercial companies’ impact on the ecosystem. Some question whether commercial rafting should be allowed at all in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area in lutruwita.

Franklin River Rafting’s no-trace commitment seemed genuine, including no fires, using the same no-structure campsites and lugging out waste. The river guides are happy to debate the relative merits (or lack thereof) of that badly policed cliché: eco-tourism. “Look, eco-travel can be lots of different things and I’ve seen some terrible eco-travel businesses,” says rafting guide Sean Murray, a former lecturer in Outdoor and Environmental Education at La Trobe University (Bendigo). “Some businesses claim to be eco-businesses because they have a recycling bin in their office. But I’d like to think that the way these trips are run you could definitely call it eco-tourism. We’re carrying out all of our rubbish and human-waste. This is ‘no trace’ because you don’t even leave footprints. There is evidence that people come down here, but there really are no signs of human interference.”

Around the time of the blockade, Sean’s mum volunteered for the Wilderness Society. At 10, he remembers attending a Melbourne anti-dam protest. A poster of Peter Dombrovskis’ Rock Island Bend hung in the family home. Do his guests have such close connections to the river? “We do get some blockaders,” he says, “but more commonly we get people who wish they had been at the blockade—who were perhaps too busy with their uni course or having kids. Most people come for the history and its significance. Some because they think it might be an exciting rafting trip, but there’s a fair chance they will leave with a deeper appreciation for the place.”

The river calms and widens into the Lower Franklin around Rock Island Bend. Dombrovskis’ misty image of the then-anonymous bend helped give a face to a landscape relatively few had seen. It was one small piece of the puzzle that helped save a large proportion of the river from being drowned.

Time is only one reason that that victory doesn’t live as large in the consciousness of modern generations as it could, according to blockader Christine Jinga (Wilderness Society Sydney Inner West action group community leader). “We’re saturated with so many problems so it’s not surprising that the sweet successes fade a little bit,” she says. “We’ve become so bombarded with so many problems: the Tarkine; salmon fishing; attempts to get luxury accommodation on the Central Highlands. I think [the blockade] certainly has been forgotten, but any of us who spent time in that environment have been touched by it.”

The former school teacher first connected with wilderness in lutruwita / Tasmania in 1978, walking the Overland Track “before any of the flash stuff appeared”. Christine’s fate collided with the Franklin while reading the Hobart Mercury on a bus journey back from another Tassie hike a few years later. ‘Holgate to dam the Franklin’, read the headline. “I had never laid eyes on the Franklin, but I sat on this bus thinking, and I’m sure I said it out loud, ‘Over my damn body’.”

Back in Sydney, Christine got involved with the Tasmanian Wilderness Society and before she knew it she was back down in Strahan completing her pre-protest non-violent training. “You could feel the tension rippling through that place when you were in town,” she says. “We were the weird crazies—‘ferals’ before they used that term.”

As the boat approached the blockade landing, a nervous Christine saw a “huge swathe of ripped earth”. The site of the scarred hillside reassured her that she had made the right decision. “You could hear the chainsaws and bulldozers. We hid in a heavily forested area [500 metres from the river]; strategically placed so 20 of us could join hands around the base of this massive Huon pine.”

After three hours of “hide and seek”, ignoring warnings to get back on the boat, Christine was arrested. It was a long, cold, sleepless ordeal, buoyed only by a piece of Vegemite toast and a cup of tea. Christine was in prison by 2am, court by 9am, then released under caution soon after.

Despite the chaos, Christine vividly recalls the exquisite silence of the landscape and her first-ever platypus sighting. The blockade lives large in her family folklore, too. “My two grandsons think it’s legendary that their grandmother’s been arrested. One high-fived me when I said it might happen again [on an Adani protest].”

Christine briefly considered a rafting trip, but only found her way back to the river on a fundraiser trip years later. A short walk around the Upper Franklin put her “in connection with the more meaningful times in my life. It’s every shade of green and every type of moss you could imagine.” She jokes that she wants her friends to sprinkle her ashes in her “heartland” one day.

The mesmerizingly dark colour of the Franklin’s tannin-tinted (potable) water is one of the biggest surprises for first-timers. We scooped water straight from the river and poured it down our hatches untreated without a hint of constitutional complaint.

How healthy is the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park ecosystem? The answer is a tale of two rivers, according to Jamie Kirkpatrick, Distinguished Professor of Geography, Planning, and Spatial Sciences at the University of Tasmania (specialising in conservation, ecology and endemic plants).

“Because the Gordon has been trashed a bit by the changes in levels, the Franklin is an important refuge for some West Coast endemic plants,” says Jamie, a member of the National Parks and Wildlife Advisory Council until recently. “[The Gordon] has had an increased incidence of lightning-fires since the late 1990s, which have burnt areas of fire-sensitive palaeo-endemic vegetation. We’ve had a massive pollution event in Macquarie Harbour from an expansion of fish-farming. The fish waste has got into the World Heritage Area. The river has been very badly disrupted by the massive changes in the flows coming from the Middle Gordon scheme.

“But in the Franklin, nothing much of any consequence has happened to degrade the catchment itself. It’s still in good nick. There haven’t been wildfires in the catchment since it was declared World Heritage—only small planned ecological burns in buttongrass moorlands. The major threat remains climate change and its implications for fires, because a lot of the ecosystems along the Franklin can be destroyed permanently by fire.”

The greater national park has faced some challenges, including being “sprinkled with low levels of heavy metals from Queenstown smelters and a very sparse population of cats”. Jamie would also like to see Mount McCall Track closed and rehabilitated—now a “total mess”, thanks to 4WD access. “It’s pretty special to have a mostly roadless and trackless catchment of such a large area, still dominated by plants that were around under Aboriginal management,” he says. Left to its own devices, wilderness can be pretty resilient. Naturally, that depends on your definition of ‘wilderness’.

“I define wilderness as areas remote from mechanised access—more than half-a-day’s walk from access,” he says. “So part of the catchment is wilderness by definition. There is a contestation of the whole concept of wilderness from an Indigenous perspective because it implies that there was no one living there—which is just not true.”

The palawa story is often left out of the Franklin narrative, according to Sharnie Read from the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC). The Aboriginal Heritage Officer points out that members of the community were on the blockade frontline “at a time when governments and a great many of the general public still didn’t believe that Tasmanian Aboriginal people existed anymore”.

Of course, the story starts a long time before that, in a rock shelter in the Lower Franklin called Kutikina Cave (formerly Fraser Cave; handed back to the First Nations community in 1995). In the early ’80s, archaeologists uncovered cultural artefacts that changed everything. “The fact that Kutikina Cave was one of the integral factors in getting World Heritage status and saving the river is overlooked,” she says. “The site, stories and Country are all very sacred to us. Its connection to our ancient life and ancestors is very strong and real.”

Sharnie doesn’t share the sacred story “because it’s one told on Country when we’re together”. She takes small community groups on rafting expeditions to see the cave; part of TAC’s rrala milaythina-ti (Strong in Country) project.

“There are very few opportunities for us to be able to get to these remote locations, to reconnect with these sacred sites, so it’s an incredibly emotional experience. We make sure there’s community and emotional support for each other. For a lot of our people, it’s the only opportunity they feel like they’re ever going to get [because of rafting costs].”

Kutikina provides a window into how the ‘Big River Nation’ adapted to their extreme environment. “They were well-versed in not just surviving the wild, cold country but actually thriving in it. The smallest of stone tools gives us a massive understanding of how the landscape was used by our ancestors.

“Our people wore ochre-mix and seal and other animal fats on their bodies, as temperature insulators and to keep dry. They would move down into coastal areas when necessary. Not just because of the cold, but also when signs indicated that it was time to move into another area for harvesting.”

The “complex issue” of (some) rafting companies visiting the site is undoubtedly a sore-point. [NB: We did not visit. Franklin River Rafting says it won’t until an understanding is reached with the Aboriginal community.] Sharnie points to a lack of dialogue between the TAC and both rafting companies and the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Services, responsible for allowing the companies onto the river.

Amongst those who engage, study or gain spiritual strength from this 129-kilometre waterway, there is one fundamental shared understanding, a concept that neo-liberal Australia cannot grasp. “So many people are focused on an economic value or something that looks like progress,” says Sharnie. “Just because the environment doesn’t change doesn’t mean it’s not progress.”

Success in this respect is judged by proliferation of mosses, mushrooms and tree species; the health of the water and wildlife; and the respect given to sacred sites. “Seeing the wilderness each time is a mental reset," says Sharnie. "It teaches you what’s important. And then you understand your role in protecting wild places like the Franklin River for future generations.”

Jill McCulloch played an important role in the early days of the Franklin campaign. Together with designer Gordon Harrison-Williams, they developed rally posters that evolved into the now-famous triangular, day-glow yellow with black lettering NO DAMS sticker. Tens of thousands of them appeared on cars, road signs, schoolbags, backpacks, and notice boards all over the country. The iconic sign was a triangular puzzle piece that helped deliver victory in the Franklin campaign.

Designs by Jill McCulloch and Gordon Harrison-Williams

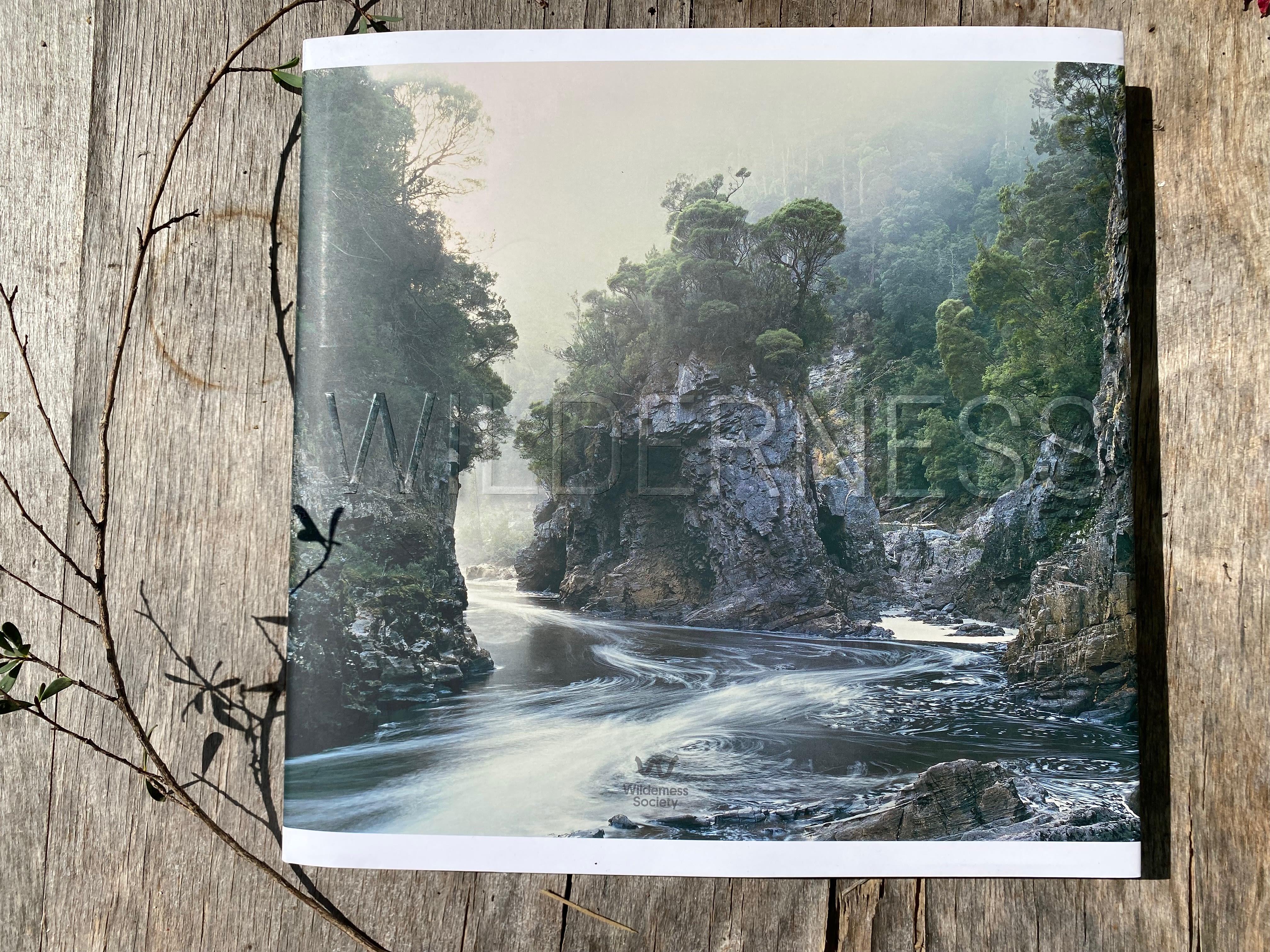

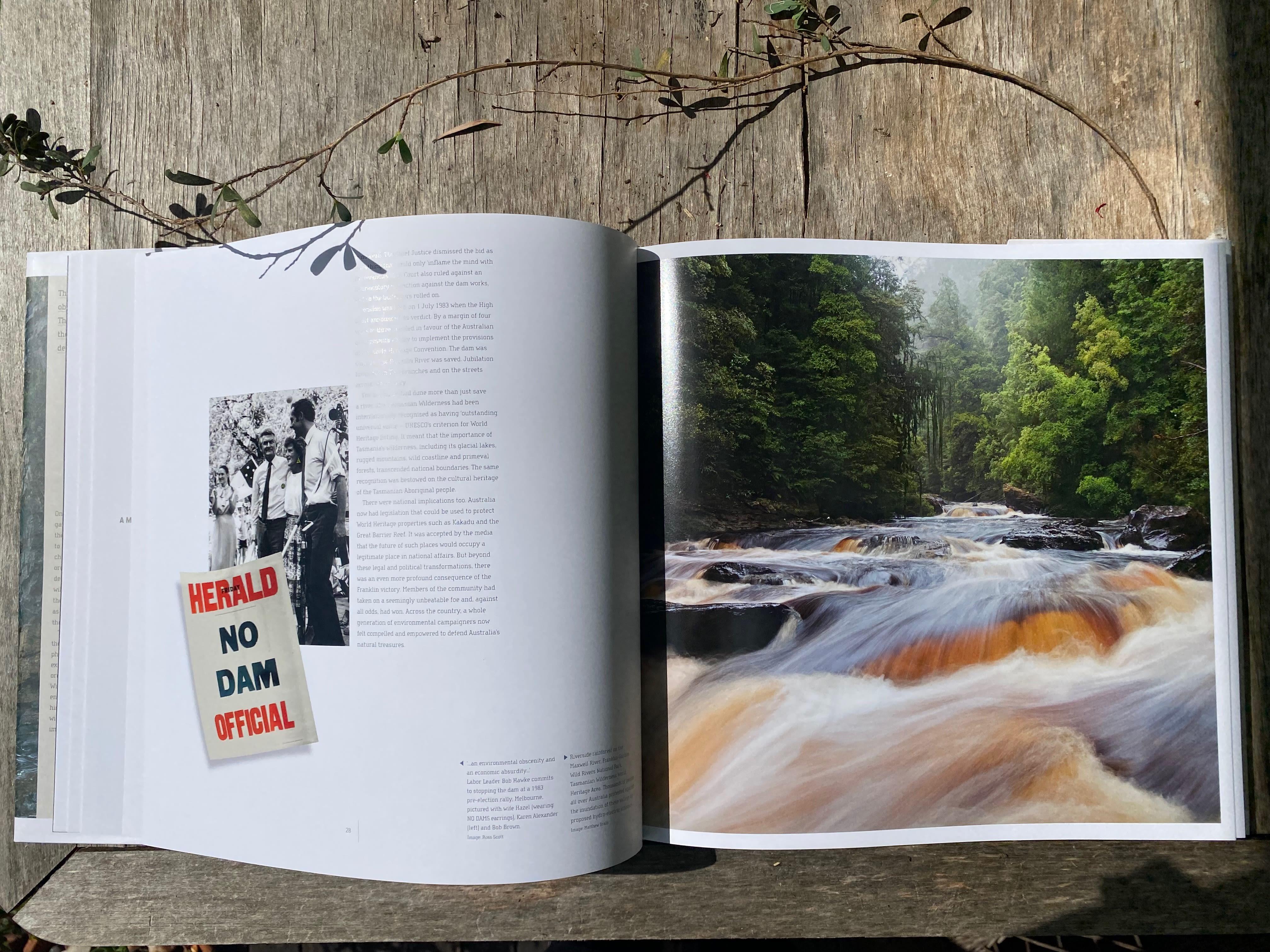

Wilderness—Celebrating Australia’s protected places covers a definitive history of the Wilderness Society from where it all began back in 1976 to some of the giant campaign victories of more recent times including Kakadu, the Daintree rainforest and the Kimberley.

With 180 pages, filled with breathtaking photographs of Australia's majestic, protected landscapes, plus rarely seen archival photos and stories, pick up a copy of Wilderness while stocks last.

Moments from the Franklin campaign.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.