Wilderness Journal #030

Welcome to this issue of Wilderness Journal, which takes a deep dive into one of the world's biodiversity hotspots, the Northern Jarrah Forests of Western Australia, the land of the Noongar people.

Image above by Daniel Jan Martin.

Noongar man Daniel Garlett describes his life in and around the jarrah forests—how everything is sacred and protected, from the bindit (ant) to the ngolyenok (black cockatoo), to the jarrah trees themselves. He's spent his life fighting to protect the forests, which he sees as his cultural obligation and a lifelong commitment

.

"I was born in Noongar land on Ballardong Country about 100km east out of Perth. Growing up in the heart of the wheatbelt, everyone knows what that means: everything that was once there is gone.

"My passion [for nature] came from seeing Country being destroyed from agriculture. Growing up on my mother's soil in the Ballardong tribe not far from Perth, it was absolutely devastating to live in that environment and walk out and see how far that [destruction] stretched. I guess from that moment on, I mourned and longed for the forest that was once there.

"From a very young age, I could relate to nature far greater than I ever could with people, and still do today, (no offence to people).

"I could see the land for what it once was—it’s a spiritual connection, a gift. My Elders say the same thing, my mother, my father, they don't understand where it came from, my ability to connect to nature. I could relate to biodiversity, the ecosystem; I didn't have a PHD, I was just a little kid, but I knew it was so important even all the way back then. I was fascinated and became a champion of the rights of our biodiversity.

"I have worked for a long time protecting jarrah forests right across the state. We only have a little pocket left—mining, land clearing and logging have seen to that. You can't get those forests and species back. Without the trees I'm lost as a human being. I wouldn't know what to do; where to go. I live in the forest to be among the trees, because it's a part of my culture. Growing up, I hunted in the forest traditionally. I have had a spiritual obligation to my family lines to protect and serve Country ever since I can remember.

"The jarrah forests were once right along the Scarp. My dreaming track goes along the mountain, from Whadjuk and all the way down to Albany, through all of that forest. Our people would stay in the flatlands during the summer down in Perth and Mandurah, all the way down the coast to Denmark. We would stay close to the ocean during summer. In winter we would all go back to the karri and jarrah trees.

"Ceremonies would happen right through the jarrah forests. There are women’s places, birthing places, there's men's lore, ochre pits for ceremonies. So we have a spiritual connection to this place.

"It's really important that we maintain and keep the jarrah forests. When they go it's a part of you that dies. And it's not just human beings affected, it's also the native species in there, right down to the insects.

"The insects are really culturally important, but no one mentions them, it’s always about the black cockatoos or the bandicoots. But to me, the insects are extremely, extremely important. We have Dreamtime stories about the ants. We have dances and songs for the ants too.

"My first relationship with nature was with a bindit (an ant). There’s a sacredness and importance to an ant that we take for granted. There's something like 200 million ants per person. You don't have to be a professor to understand the importance of what they do. I don't even like stepping on an ant; we shouldn't be disturbing and destroying things in their environment. If I step on one, I say 'I'm sorry about that’.

"The ngolyenok (black cockatoo) is a close totem to me, on one side of the family it's an owl, and on the other side it's the ngolyenok.

"They come here and eat in my trees at the front of my house. They are harbingers of rain, but also spiritual message birds. If they come and stay here and sing all day—it means I'm going to get a visitor, and I always do.

"Our lore people, the men, used the red-tail cockatoo feather for ceremonies. They would come up here, where I live, to the lore grounds, up in the mountains, and they have burial grounds up here too. They would come up and collect the feathers. They would be able to do that all the way down to the ocean, but not any more, we're getting pushed out further and further.

"What's really disturbing about that is that what is happening to the ngolyenok happened to us people.

"The ngolyenok is a really, really close totem of mine. I would be devastated if they went extinct.

"The thing that a lot of people don't understand, who don't understand this Country, is that we have totems for a reason: to protect species and not kill them. So the ngolyenok is a totem of mine and one that I can't kill. And the reason why we do that is to maintain a sustainable world for future generations. And that includes trees. That's why we have totems so that we're all not eating or using the same thing. So if your totem was a jarrah tree, that means that not everyone wants the jarrah, only a certain few want it. But the whole world wants jarrah it seems. And what happens to the jarrah? It gets destroyed.

"And that's where human compassion and empathy come in. As a human being and a good humanitarian, in the efforts of saving the environment, you need to ask yourself, ‘Do we really need all this?’ If we all want the same thing, none of it will be left. And you can't regrow the jarrah forests.

"As the oldest, continuous culture on the face of the Earth, we have a job to do. My connection to Country means I have a cultural obligation to protect and serve our environment. It's a lifelong commitment."

Words by Tom Kealy

This year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sounded the alarm on forest degradation in Western Australia’s Northern Jarrah Forests. As land clearing for bauxite production continues in the region, there are doubts that it’s possible to successfully rehabilitate this iconic landscape, with urgent calls to protect what’s left. An investigative report.

Just over an hour south east of Perth, the sprawling, urban tide of the western capital yields to the hills. Here, on the Darling Scarp, development is largely forgotten within a region that’s a biodiversity hotspot.

Scores of endemic plants flourish within this ecosystem. Recently, botanists identified two new orchids in the forests previously unknown to Western science.

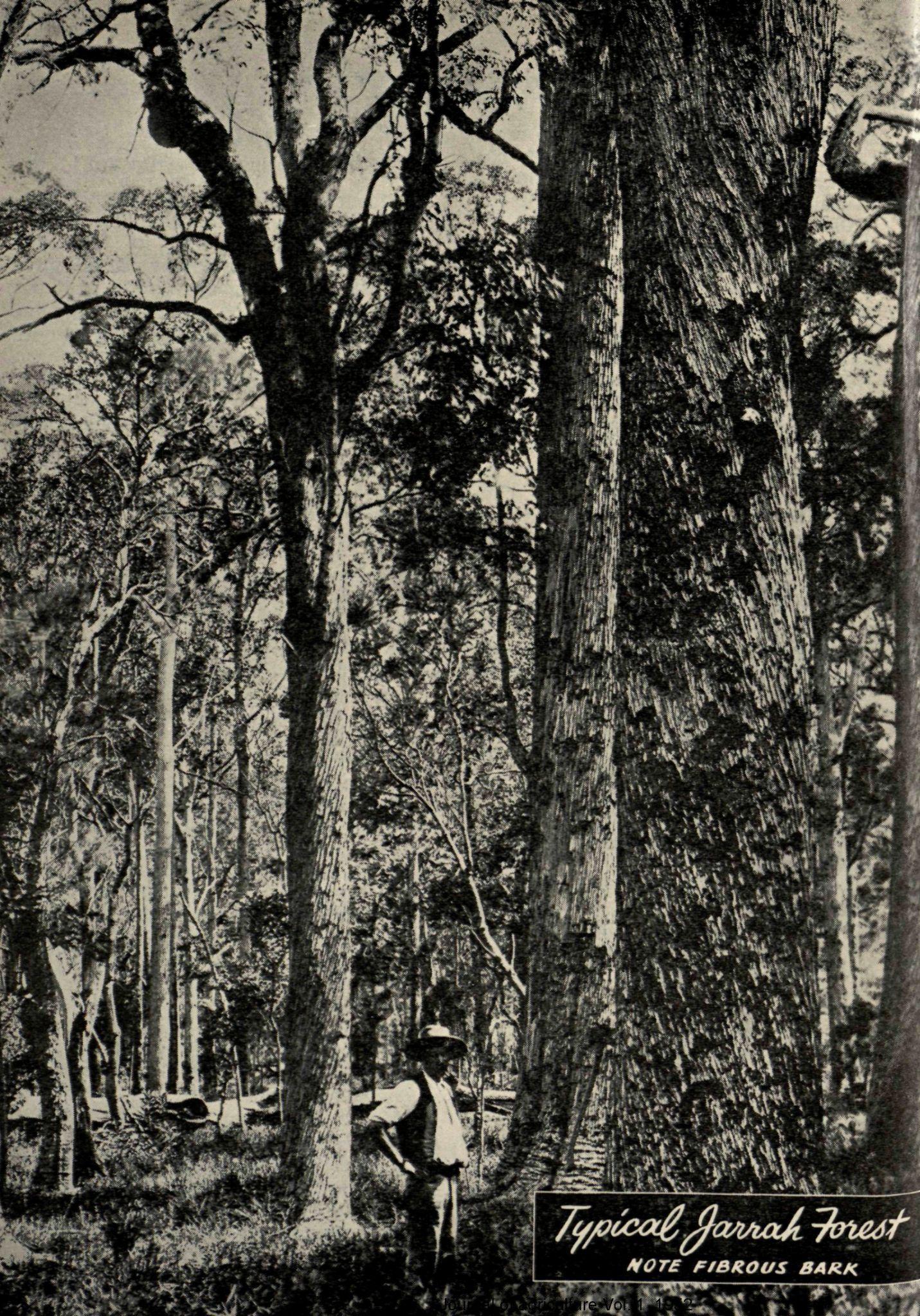

And yet, even among this botanical richness, the region is perhaps most famous for one plant in particular: the grey-barked, dark-timbered jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata).

One of the best places to see these iconic trees—known as djarraly in the Noongar language—is the former forestry town of Dwellingup. Jarrah timber from Dwellingup and surrounding hamlets once formed the bedrock of Western Australia’s economy, its usefulness as a hardwood ensuring that it was chosen by British authorities to literally pave the streets of London in the 19th century.

But with an environmental consciousness growing among the people of Western Australia in the second half of the 20th century, and through activism by organisations including the Wilderness Society, those days are long gone. In an overdue announcement made late last year, the state government declared that native forest logging will cease by 2024. Western Australia will be the first jurisdiction in the country to make this transition.

The move has not seemed to bother Dwellingup too much, though. The town itself has already transitioned into an outdoor tourism hub. For years now, trail walkers and mountain bikers flock here on weekends to embrace the bushland that fringes the town on all sides.

But these trails, verdant as they are, shield another form of forest degradation that is nowhere near as well-known as logging.

A few short miles from Dwellingup’s town centre, down tracks that forbid the general public from entering prohibited areas, the bushland drops away to reveal scenes of devastation. These are not logging coupes but the operations of global aluminium leader, Alcoa, which mines the region’s soils for the rich bauxite deposits they hold.

Patches are carved out of the hillsides with little if any vegetation or debris in sight. There are no signs of the numerous bird species which call this place home, which include endangered black cockatoos (Calyptorhynchus) or their marsupial neighbours—the western ring tailed possum (Psuedocheirus occidentalis), the chuditch or western quoll (Dasyurus geoffroii) and the mainland quokka (Setonix brachyurus).

If not for the hum of cicadas, you could be on Mars.

“Even for those of us in the environmental community who are used to these things, the nature of the mining operation is extremely confronting,” says Patrick Gardner, the Wilderness Society’s West Australia Campaigns Manager. “To access the bauxite, the forest has to be clear felled, the topsoil is removed and expansive pits are excavated. It becomes like a moonscape.”

This area, known as the Northern Jarrah Forests (NJF), has been the sight of tension since Alcoa began operations here in the 1970s. The multinational, based in the United States, is the world’s second largest producer of aluminium. It now operates Huntly, the world’s second biggest bauxite mine set within the jarrah ecosystem.

Since bauxite mining operations began on Perth’s doorstep, environmentalists—including the Wilderness Society’s WA campaign centre—have argued that land clearing forces out fauna and does not allow native flora to flourish. Alcoa, on the other hand stands by its rehabilitation credentials, which include replanting natives into areas that have been previously mined.

Patrick Gardner, however, says that there is considerable evidence to suggest that the stronger stands of jarrah, including their broader biodiversity values, are dependent on higher grades of bauxite within the composition of the soil.

“We believe there is merit in the state's Environmental Protection Authority undertaking an assessment of the Northern Jarrah Forest and the cumulative and retrospective impacts brought about through bauxite mining and other practices,” he explained.

This call comes at a time when the very future of the NJF is at stake, receiving international focus in a rapidly warming world.

In February this year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Sixth Assessment Report. In its findings, it highlighted key ecosystems around the globe that are at greatest risk from a changing climate. Among those singled out in Australasia was the NJF, with the report finding with “high confidence” that jarrah forests are at risk of “transition or collapse…due to hotter and drier conditions with more fires.”

Consequently, the report recommended “avoiding and reducing forest degradation from inappropriate forest management practices and land use.”

Grant Wardell-Johnson, who is Adjunct Associate Professor at the Centre of Mine Site Restoration and School of Molecular and Life Sciences at Curtin University, cautions a consistent trend of declining rainfall in the south-west region since 1970, which has already led to a fundamental structural change in the jarrah forests.

“Research has shown a loss of forest height, biomass and structural integrity,” he explained.

Within this drying climate, Professor Wardell-Johnson advised that the water table within the NJF has also dropped, and is therefore likely to reach bedrock within this decade. What this means is that jarrah will have to survive on rainfall alone, upon soils that are easily damaged by disturbance such as logging and mining.

“The soils of the jarrah forest are ancient, but have sustained these forests for millennia,” Professor Wardell-Johnson said.

While logging in this drying climate has resulted in increasing forest susceptibility to damaging wildfire, bauxite mining removes and disturbs the substrate, which has allowed the forest to evolve over thousands of years.

This, Professor Wardell-Johnson said, “permanently changes jarrah forest systems”.

And then there is the question of old growth forest. The IPCC report concludes that “no amount of tree planting will be enough to cancel emissions. Preserving the world’s forests…and other natural carbon stores is essential.”

While most of the NJF have been historically cleared—meaning it is not “virgin,” or unlogged, forest—there are patches that have grown back that may be well over 100 years old, with significant understory that also houses many marsupial and bird species. These hold significant stores of carbon, and also contain trees that were left standing by the logging industry and predate European colonisation.

Alcoa has consistently maintained that it does not mine in gazetted national parks, nature conservation reserves, old growth forest or other areas of high conservation value.

But Patrick Gardner says that this declaration is misleading.

“The definition of ‘old growth forest’ is still being reassessed and identified,” he said. “This is in part due to a questionable legal definition that disqualifies forest from being designated as 'old-growth,' despite being hundreds of years old.

“Some of these trees have been there since before European settlement. They are absolutely essential habitat for many species such as black cockatoos. It will be centuries before these recently planted trees are able to provide sufficient nesting hollows for these birds.”

In order to address the IPCC report’s findings, Professor Wardell-Johnson believes that rather than focus on trying to rehabilitate areas after clearing, conserving what is left of the NJF is imperative, with these forests becoming increasingly homogeneous and losing diversity across their range.

“Mining results in functional change, regardless of the rehabilitation approach,” Professor Wardell-Johnson said. “Further disruption of these iconic forests will submit them to devastating pressure and irreversible change.”

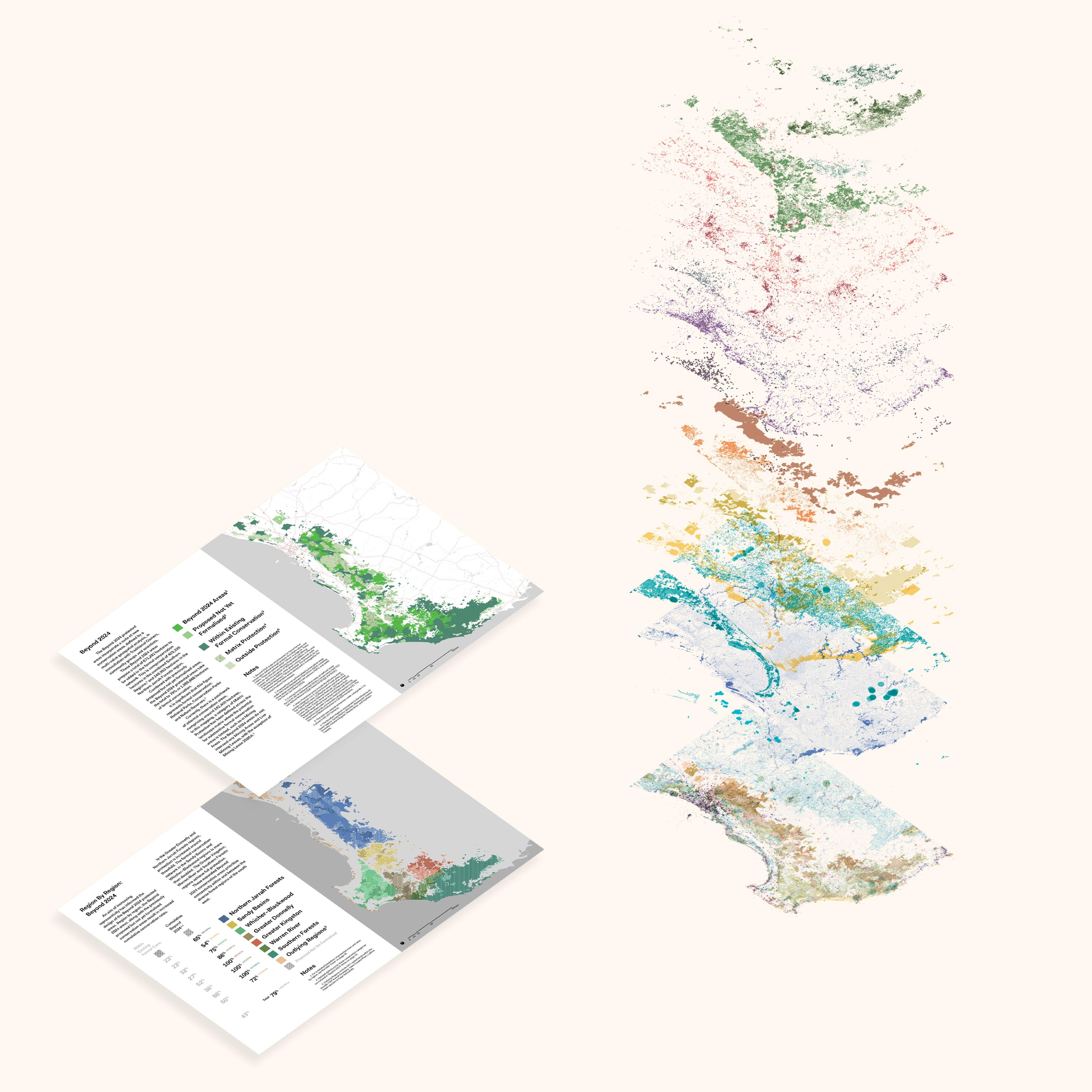

Daniel Jan Martin is an environmental planner, designer and geospatial analyst based in Walyalup / Fremantle. He grew up in the jarrah forests. Daniel's work, at the intersection between art and science, highlights the urgency of protecting these landscapes.

Wilderness Journal thanks Daniel Jan Martin for sharing his story and these previously unseen images: combinations of mappings, photography and artworks which make up the upcoming Forests Atlas. Credit: Daniel Jan Martin, Alice Ford, Nansen Robb and Clancy Martin. In conversation with Rachel Knepfer.

What is your personal connection with the forests and that part of the world. Has growing up in and around the bush shaped your working life?

I grew up in the south west of WA in Torbay, between the valleys of knobbly coastal karri forests and hobby farms. Jarrah and marri trees all dotted between. Life revolved within this isolated but extensive ecology.

As a kid I’d learn to whistle like the birds, and obsessively draw the marsupials. After I finished school, university took me to Perth, which was the biggest city I could imagine at the time. I saw it, and still see it, through a lens of nature.

We are in one of the most biodiverse parts of the planet here in the south west. Perth remains the epicentre of this diversity, and its destruction. The forests that start here extend as an arc nearly 500 kilometres south, back home to Torbay. The jarrah and marri forest dominates in the north, and those jarrah forests between Perth and Collie are facing so many threats now and in the years ahead.

I feel that studying and working in practice as a landscape architect and environmental planner has taught me to understand the ‘city’ ways of seeing. But younger years do shape you. I still feel like I’m looking through the other end of the microscope—through the macroscope!

What motivates this work for you?

Fracturing and polarising are becoming themes of a century that needs to be about unity. The world seems to be calling out for translators, of all kinds. To see something there, interpret it here, express it over there. Translators are emerging everywhere and what they seem to have in common is that they sit in spaces between. They can harmonise perspectives, gather disciplines, and cultures.

When I encounter nature, I see networks. In ongoing disagreement with human boundaries. The river doesn’t stick to the line on the map. The aquifer doesn’t care about the lot boundary. The dunes, the valleys and the forests—they are all just as fluid. I find great beauty in drawing and mapping these networks. It becomes an act of resistance against the drawing of boundaries. To draw and map becomes an act of translation, communication—passing on an awareness, an urgency, a wonder.

What is mapping?

I have come to see mapping as translations into the language of space. Be it ideas, boundaries, networks. The minute you map something it is given power—as if it could now happen. This can be violent—when you translate violence. A logging plan, the sandpad over woodland for a housing subdivision, a territorial invasion. It is healing—when you translate care or repair.

Mapping operates across many domains, it is both an art and a geospatial science. You can encounter a map visually or aesthetically. But you can also measure it. You can see things in spatial terms, you can sense and measure change, loss and growth very easily. You can look back and look forward with maps. To highlight damage before it becomes a physical reality and map future scenarios, to create a canvas for conversations and careful ways forward.

We are also in the process of publishing the Forests Atlas, a book which blends mapping, art, photography and language in celebration of the richness of the south west forests. This project has been undertaken with a range of contributors including Alice Ford, Nansen Robb, Clancy Martin and Adam Bahar, alongside Aboriginal Elder Dr Noel Nannup. We have been working on this project alongside the WA Forest Alliance.

Callan Wood is a self-proclaimed orchid obsessive, a result of growing up and living by the Northern Jarrah Forests of WA. The forests are host to an extraordinary diversity of wildflowers and pollinating insects, which Callan has been photographing for many years.

Interview by Emily Wood-Trounce, photography by Callan Wood.

How did you develop such a deep interest in the orchids of the jarrah forests?

Well, I've lived in Perth my whole life, in the foothills of the Jarrah forests. From a very young age my parents would take my siblings and I bushwalking through the jarrah. You can't do that without building relationships with the organisms that live there. Orchids are a particularly fascinating element of this landscape to me.

Are you an orchid enthusiast? A naturalist?

I actually do prefer ‘naturalist’. It’s an old term that was quite popular in the 1700s, before we started splitting up all these fields of research; mycology and botany and so on. I think the more time you spend in nature, the more you realise that we can't separate these things because it's all one integrated ecological system. ‘Naturalist’, I think, is a good term to bring back, especially when we’re talking about orchids, which are so interdependent with the organisms around them.

What are some of your favourite orchids in the Jarrah region.

A common one is the cowslip, Caladenia flava, which is vibrant yellow with red splotches on it, growing only to about 10 centimetres high. You can get carpets of this stuff all over the forest floor. And dotted among these carpets you’ll get a really strong colour contrast with other flowers, like the blue silky orchids, Caladenia sericea. They're a beautiful vibrant, bluey purple. They tend to be a little more scattered than cowslips, and usually only have one or two leaves, but they're quite beautiful.

You can even find some that have very strange shapes, not resembling what most people would consider a flower. Like the Pterostylis barbata, or bird orchid, which looks almost like a hummingbird—it has a beak, a head, and a modified labellum that looks identical to a wispy little emu feather. The bird orchids are totally bizarre. They produce pheromones which attract small flies to come up inside the flower, which is kind of like a hood. The insect is coerced up to hit the anther, which deposits pollen grains onto its back, and then it flies out of the orchid to find another to pollinate.

That sounds like a remarkable relationship between the flower and its pollinator.

It’s amazing. Orchid reproduction is incredibly dependent on other organisms. The pollinating insects are an important one, and often being coerced with sexual mimicry, through their shape and the pheromones they produce.

Hammer orchids, the Drakaea genus, are equally fascinating. As well as emitting those pheromones, their very structure mimics the female thynnid wasp, attracting the male pollinators. The male wasp comes and lands on the orchid and literally tries to take off with it, and the flower hinges like a fulcrum and dabs the male wasp with pollen. I've seen this happen in the wild before and it's a pretty violent thing. It happens quickly, and the whole flower will be swaying back and forth until the wasp eventually lets go and flies onwards.

What about beyond the insects—what other relationships do orchids have with their environment?

Well, fire is also really important for the germination of a lot of orchid species, some so much so that they actually need fire to flower, and thus reproduce. For example, with red beaks orchids, Pyrorchis nigricans, you can find unburnt areas in the forest with carpets of their flat, heart-shaped leaves, with not a flower in sight. But if a fire has come through, only then will they actually shoot up a stalk and produce a flower. So the relationship with fire is very important in the Jarrah.

Beyond this, a particularly interesting relationship exists between orchids and mycorrhizal fungi. That's 'myco', meaning 'fungi', and 'rhizal', meaning 'root'. It's a category of fungi that gets nutrients for plants and delivers it to them through their root system. Often a specific species of fungi is only associated with one orchid, so the species are dependent on each other.

What's different with orchids compared to other plants, is that not only does the fungi transmit nutrients through the soil, but that fungi is actually with that plant from its germination as a seed. These seeds will not germinate without that specific species of fungi coming up to the surface of the soil. The hyphae, these thin tube-like threads of mycelium, latch on to the seed and they activate its germination. As the orchid starts to grow, it actually keeps a little bit of the mycelium within it, which spreads little threads of hyphae throughout the soil, collecting all the nutrients that are needed for the orchid to grow and flower.

Sometimes you’ll stumble across a colony of orchids, with many flowers in one small area. These are all genetically identical orchids, which have sprung up from a single tuber, which is like an underground starchy energy store for the orchid. And even though those flowers you're looking at might only have bloomed for that year, the underground network that produced them could be many years old. So even though they're flowering annually, the plant itself can be a lot older than that.

So what should people do if they see an orchid in the Jarrah?

Well, appreciate it for one, and take some photos. If you have time to sit and wait, sometimes you will be lucky enough to see a pollinator visit. But definitely don't touch them. Orchids are extremely delicate, the oils on your fingers can do a lot of damage even from a gentle touch.

You then determine what type of orchid it is, as best as you can. There are lots of field guides, as well as websites/apps that can assist, one is iNaturalist, which is full of other enthusiasts that can help with identifying the species. If you're lucky enough to find a threatened or priority flora species it might be worth ensuring that the precise location is obscured on public online platforms like iNaturalist, but then consider sharing the location with your state government department that manages the threatened flora. Once you work out what species it is, you can determine whether it's something worth forwarding to your state government department that manages threatened flora. We can then keep help track of populations and ensure they are protected.

Environmental filmmaker Jane Hammond introduces Black Cockatoo Crisis, a film the Wilderness Society has been proud to join as an associate producer. Premiering on 23 November, it's an urgent appeal to stem the decline of some of WA’s most charismatic birds, which depend on the jarrah and karri forests.

Photography and film courtesy of the filmmaker Jane Hammond. Watch the trailer below.

"I had been trying to film black cockatoos when I was making Cry of the Forests, an earlier film about the plight of the South West forests of WA. The forest red-tail black cockatoo cry lends itself to the name of that film. So I had this sort of intermittent connection with the birds during that production, and I thought these were just the most wonderful creatures.

"I wanted to make something about them. Tragically, our forest red tails, Carnaby’s and Baudin’s black cockatoos are all on the path to extinction. Initially I was going to make a five-minute film to help launch a campaign with WA Forest Alliance. But as soon as I started filming, I realised that this story needed real screen time for people to engage with these birds. They’re so beautiful and smart.

"Personally, I love the Carnaby's. The red-tailed cockatoos are so pretty, but the Carnaby's have just got so much character and are so cheeky. They are just so cute with their little red eye rings and tiny little crowns, whereas the red-tails are very magnificent with their big crowns. But yeah, nothing beats a Carnaby's for character.

"The white tails are quite rare because we've got red-tails in other parts of Australia but no other white tails on the planet.

"There's 60,000 years of deep connection to these creatures. And yet Europeans have only been here a couple of centuries and we're wiping them out. So something has to change. And so that's why I wanted to make the film. There's something special about these birds; they are so knowledgeable.

"We need to save every last one and some people try and do this. Kaarakin Black Cockatoo Conservation Centre features in the film. It is run by volunteers mostly and a few staff members. And those people are just the most giving, wonderful human beings. They just love cockatoos. So in the film we look at one volunteer, a retired public servant. Last year she did 25,000 kilometres travelling the state, picking up injured cockatoos and ferrying them back to Kaarakin. There they get looked after by staff and volunteers for a year or so, after they've been to the zoo to be patched up. They care for them, rehabilitate them, and are really careful not to handle them too much so they can be released.

"Making a film like this takes everything out of you. It's actually quite physical. Some of the cameras that I've been using on this one were really heavy. It's like you're having a workout.

"But filming these birds is just an absolute joy. It's taken me a year to learn the skills because it's just a very different form of filming.

"The Northern Jarrah Forest is such a beautiful and intact large area of forest, even though it's fragmented by mining and all sorts of other things. We have a chance to turn this around. And that's what the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's warning about the Northern Jarrah Forest was about. We have a chance to fix it if we act now. We can save the forests and these birds.

"Black Cockatoo Crisis is a universal story. It's not just about these black cockatoos; they're just like the example. We're squeezing them every which way and they’re incredibly adaptable. But every time they adapt, we take that away from them too. So we're just attacking them on all fronts. And that's what we've got to stop. We need effective emergency recovery plans for these creatures, and we've got to do that urgently.

"Thank you so much to the Wilderness Society for the support that they've given this film."

Black Cockatoo Crisis is showing at Luna Leederville, WA, from 1 December, before playing at theatres all over Australia. Check the film’s Facebook page for future screenings. The film's world premiere on 23 November has already sold out.

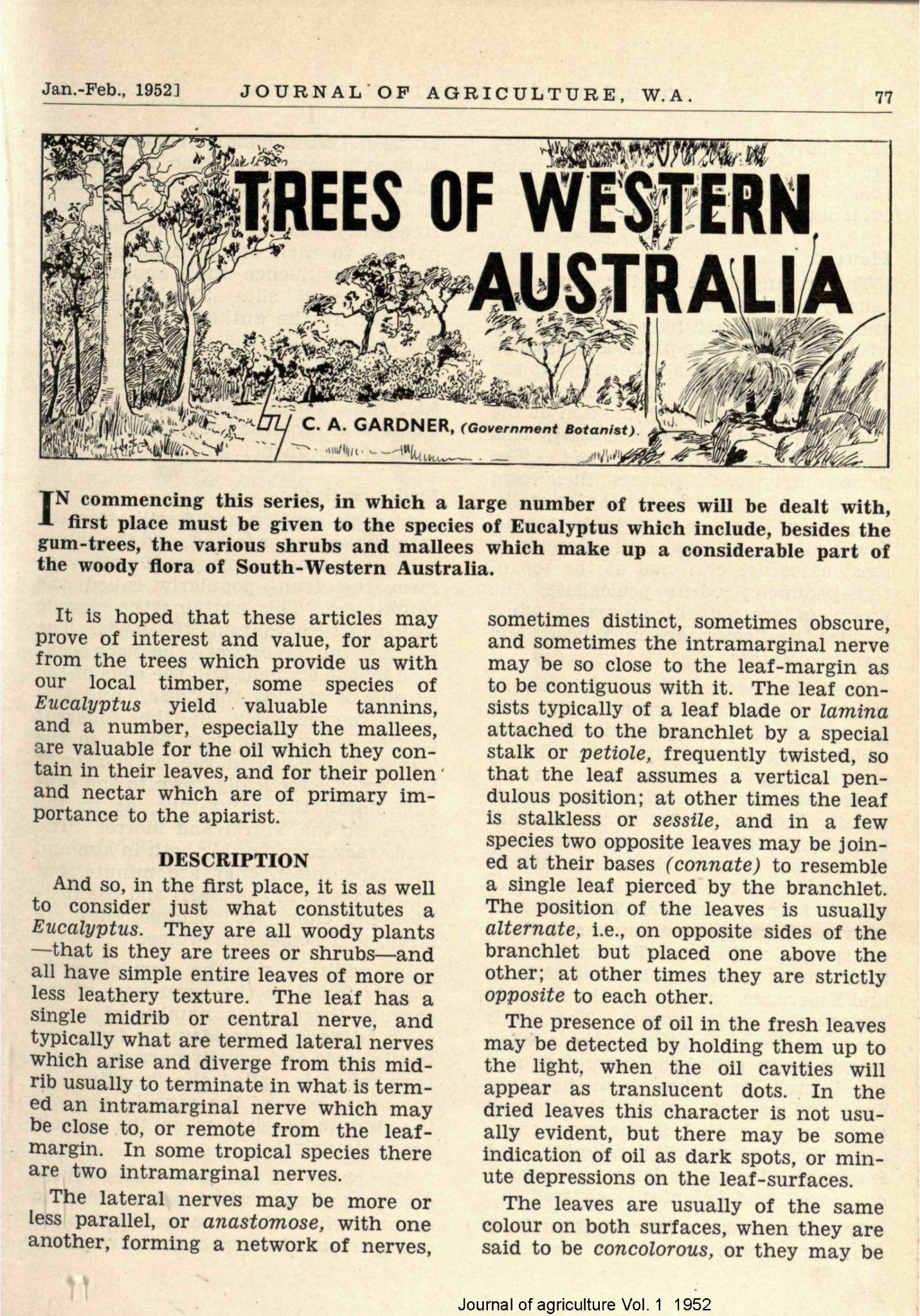

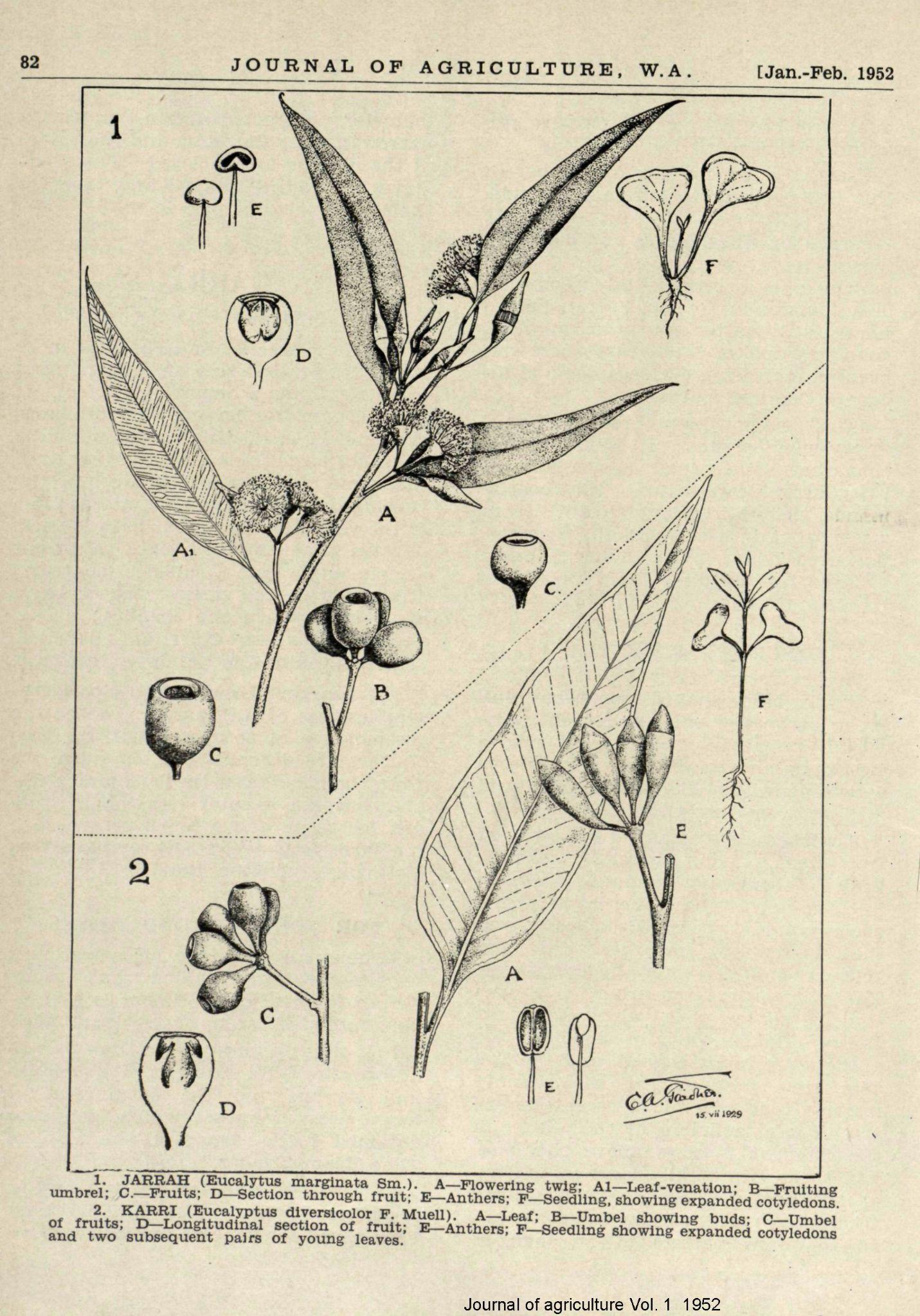

Excerpts from a 1952 government publication, the Journal Of Agriculture, WA, 'in which a large number of trees will be dealt with'.

We recognise First Nations as the custodians of land and water across the continent of Australia and pay our respects to Elders past and present. We acknowledge sovereignty was never ceded.

In this issue we particularly acknowledge the Noongar people—the Traditional Owners and ongoing custodians of the south west of Western Australia.